Howard Fischer

Uppsala, Sweden

|

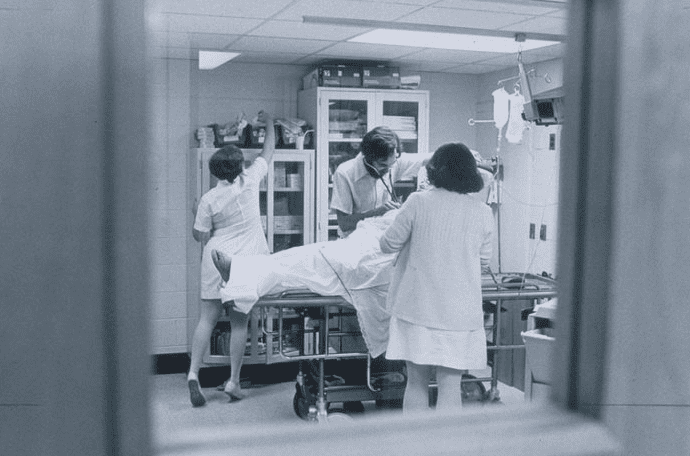

| Virginia Emergency Room, image from “Historic VCU: A VCU Images Special Collection” VCU Libraries from Richmond, VA, USA, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons |

Finally, it was my first day in a US hospital after studying medicine in Europe for five and a half years. A medical education at the very old and renowned Belgian university at which I studied lasted seven years. The school let its foreign students return to their home countries for the last year and a half for clinical rotations. I arrived late at night in Detroit, went to the hospital-owned apartment, and spent a mostly sleepless night anticipating my first day in an American medical setting. My Belgian education had been in French. Would I know the US medical vocabulary? What about the abbreviations? Would what I learned in Europe correspond to what American medical students learned?

I awoke, skipped breakfast, and walked the two blocks to the hospital. I was given a lab coat, a hospital badge, and a tour of the hospital. At about eleven o’clock my tour brought me to the Emergency Room. After a few minutes, an intern, an American who had been ahead of me in school in Belgium, called me over. He led me to a curtained-off space where a man of about fifty laid supine on a gurney. The intern was trying to insert a Foley catheter in the man’s urethra. It would not go in very far and the patient had much discomfort. (I quickly learned that’s how American physicians described a patient in pain.)

“Hey,” the intern yelled, “did you ever put in a Foley?”

Surely he knew I had not; in our preclinical education in Belgium, we barely laid a hand on a patient, much less did any kind of procedure.

“No,” I told him.

“OK, here’s your first,” he said.

I approached the patient without hesitation. We had learned how to catheterize the male urethra in school—they just never actually let us do it. While the intern and I had this brief conversation, the patient kept repeating the same thing while my colleague tried to advance the Foley: “Stop! There’s a stone in my penis.”

Now it was my turn. Stone in the penis? What could that possibly mean? The first thing I thought I would do was remove the Foley that was currently inserted partway, re-prep the patient, and insert a fresh catheter using sterile technique. I put on exam gloves, held the man’s penis in one hand, and pulled out the Foley with the other. As the distal end of the Foley left the urethra, a geyser of bright red blood spurted up into the air from the meatus. I felt myself getting very warm. My field of vision was more and more like a tunnel.

People were standing over me when I awoke, now supine on a gurney myself. “Are you a diabetic?” “Has this ever happened before?” “Did you have any breakfast today?” I drank the orange juice someone offered and sat up. I was OK and said so, and no, I had not had any breakfast.

While I had been fainting for the first time in my medical career, my intern colleague decided to find out why the Foley would not pass. He placed a thin metal probe down the man’s urethra, and sure enough, there was a clinking sound—the sound of metal tapping against stone. The patient had a history of bladder stones, which sometimes migrated into his urethra. He did, indeed, have a stone in his penis.

I was sent to the cafeteria for lunch, then ordered back to my hospital apartment for a decent sleep with instructions to start my first rotation the next morning. What did this episode teach me? It re-taught me that what I had learned in the classroom was true: the brain cannot function without glucose. I never skipped a meal again while on duty, even if that meant just eating a candy bar as the admissions were piling up. More importantly, I understood that the careful physician knows a patient’s history well before undertaking any form of intervention, even something as “simple” as inserting a Foley catheter. And, of course, I learned that not every classmate or colleague should automatically be considered a role model.

HOWARD FISCHER, MD, was a professor of pediatrics at Wayne State University School of Medicine, Detroit, Michigan.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Personal Narratives

Leave a Reply