JMS Pearce

Hull, England

|

| Figure 1 WHR Rivers in public domain, from Wikimedia |

William Rivers MD FRCP FRS (1864-1922)

William Rivers (Fig 1) was a most unusual man, a polymath with careers in neuroscience, ethnology, and psychology. But above all—notwithstanding or perhaps because of personal nervous constraints—he was a man of originality and great humanity.

Son of a churchman, he was born in Luton, near Chatham in Kent, and attended Tonbridge School. He read medicine at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, qualifying in 1886. His first attraction to the nervous system was when he became house physician at the National Hospital for the Paralysed and Epileptic, where he met Hughlings Jackson, Michael Foster, Henry Head, and Charles Sherrington, and secured the MD Cambridge and FRCP London. He left the National Hospital in 18921 and traveled to Jena, where he worked with Ewald Hering. During his visit his diary discloses a turning point in his ambitions:

“I have during the last three weeks come to the conclusion that I should go in for insanity when I return to England and work as much as possible at psychology.”

He was appointed clinical assistant at Bethlem Royal Hospital, and gave lectures on mental illnesses at Guy’s Hospital. He also studied and lectured on experimental psychology. In 1893 Rivers spent the summer working in Heidelberg with Emil Kräpelin, investigating the physiology of fatigue. In 1897 he was appointed Lecturer in Physiological and Experimental Psychology in Cambridge. He then worked as a ship’s surgeon, traveling to Japan and America. During his travels he pioneered the experimental study of mental functions among preliterate islanders of the Torres Strait. From these studies he introduced genealogical methods into sociology in several books. This was recognized by his election as a Fellow of the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1890.

He worked with vigor, contagious enthusiasm, and zeal for scientific precision in his methods and writings, but fatigue sometimes restricted his hours at work.2

In 1907 he was made director of Cambridge’s new psychology laboratory, the first of its kind in Great Britain. He became joint editor of the British Journal of Psychology. In May 1908 he was elected FRS and was awarded its Royal Medal in 1915. He was also awarded honorary degrees from the universities of Manchester, St. Andrews, and Cambridge.

Shell shock

Certain disabling but controversial symptoms incurred in World War I were extensively documented. Their psychological basis was recognized by 1915.3,4 This led Rivers to new approaches to shell shock, which was estimated as affecting 80,000 British cases of war neurosis. Traumatic neurosis was the title given in 1884 by the neurologist Hermann Oppenheim, who had described forty-two cases caused by railway or workplace accidents,5 though Charcot ascribed symptoms to hysteria or neurasthenia. Rivers was aware of many earlier writings describing serious emotional reactions both to industrial injuries and the horrors of war. Soldier’s heart, shell shock, war neurosis, névrose de guerre, and Kriegsneurose were familiar terms.

When he was commissioned as Captain in the Royal Army Medical Corps, the prevailing opinion of many military authorities was that the condition was caused by insanity, hysteria, or malingering. Rivers, by contrast, maintained that war neuroses did not result from war experiences themselves, but were “due to the attempt to banish distressing memories from the mind.” In line with Freud’s abreaction, he encouraged his patients to remember and talk about their horrifying experiences of warfare, instead of repressing and trying to forget them. He used techniques of suggestion, persuasion, re-education, and hypnosis.6

He applied this principle to treat shell-shocked patients from July 1915, first at Moss Side Military Hospital at Maghull, near Liverpool, then from October 1916 at Craiglockhart Hospital for Officers with Nervous Diseases near Edinburgh.7

On 4 December 1917, he addressed the Section of Psychiatry of the Royal Society of Medicine on The Repression of War Experience; in February 1918, this paper was published in The Lancet:8

Because I advocate the facing of painful memories and deprecate the ostrich-like policy of attempting to banish them from the mind, it must not be thought that I recommend the concentration of the thoughts on just such memories. On the contrary, in my opinion it is just as harmful to dwell persistently upon painful memories or anticipations and brood upon feelings of regret and shame as to banish them wholly from the mind.

Rivers warned that repression risked passing men who are unwell as fit for service. This “can have but one result when he is again faced by the realities of warfare—a second breakdown, or suicide.” His pioneering work was an essential element in the general acceptance of shell shock as a genuine psychological illness.

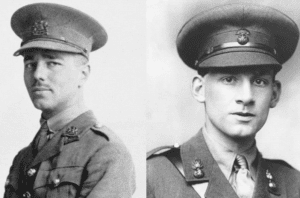

Rivers was much loved and admired. Among the patients he befriended were the literati,9 Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon, and Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) (Fig 2). After being blown up by a shell, Owen in June 1917 was sent to Craiglockhart Hospital, where he spent four months. In September 1918 he returned to the front and was awarded the Military Cross for bravery. He was killed aged twenty-five, one week before Armistice. His legacy was his poetry: Dulce et Decorum est, and Anthem for Doomed Youth.

|

| Fig 2 Wilfred Owen & Siegfried Sassoon. Source |

“Mad Jack” Sassoon, like Owen, was awarded the Military Cross. Wounded in 1917, he caused public outrage when his “Soldier’s Declaration” denounced the conduct of war; instead of a court-martial the Army Medical Board conveniently diagnosed shell-shock and dispatched him to Craiglockhart for “treatment.” He returned to the front and despite being shot in the head (by friendly fire), recovered. After the war, he arranged for Owen’s poems to be posthumously published. Sassoon appears in Rivers’ work on shell shock while Rivers appears in several poems written by Sassoon. Sassoon’s fictionalized autobiography The complete memoirs of George Sherston (1980) extols Rivers almost as a demi-god who saved his life and soul. In his preface to Medicine, Magic and Religion, 1924, Sassoon wrote:

I would very much like to meet Rivers in the next life. It is difficult to believe that such a man as he could be extinguished.

The novelist Pat Barker chronicled his life and her meetings with Sassoon in her highly praised Regeneration trilogy (1991).

After the war Craiglockhart closed. Rivers returned to Cambridge where he concentrated on psychology, sociology, and ethnology. He died on June 4, 1922 from a strangulated hernia. The distinguished scholar Sir Frederick Bartlett FRS wrote:

Never have I known so deep a gloom settle upon the College [St John’s, Cambridge] as fell upon it at that time. There was hardly a man—young or old—who did not seem to be intimately and personally affected. Rivers knew nearly everybody . . . As a man, we think of his eager and unconquerable optimism and his belief in the possible greatness of all things human.10

It was more than fifty years later that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was named.11 The story is a telling example of the role of society and politics in the process of invention rather than discovery. The proponents lobbied hard for US veterans of the Vietnam War to receive specialized medical care under the new diagnosis, which replaced older diagnoses of battle fatigue and war neurosis. Many diagnosed as having PTSD do have clinically significant psychiatric dysfunction, however it is labeled. But PTSD became one of many non-diseases that are shaped as much by social concepts as by psychiatric ones.12 It resulted in a medicalized trauma industry. What has remained constant from Rivers’ work at Craiglockhart is the importance of a compassionate but scientific approach to those afflicted by pain and mental distress.

Sensory nerves and dermatomes

Neurologists especially remember Rivers for his groundbreaking work with Sir Henry Head on the evolving sensory signs after section of Head’s radial nerve. It was in Cambridge in 1903 that Head persuaded the surgeon James Sherren to divide the superficial ramus of his own left radial nerve. After the operation, Head and Rivers “for five happy years worked together on weekends and holidays in the quiet atmosphere of (Rivers’) rooms in St John’s College,” mapping the changing cutaneous sensory loss.

This experiment led to further investigations of sensation in which Head began to reveal an organization of sensory afferent nerves. Examining many patients with shingles (herpes zoster), Head and Campbell in 1900 mapped the skin eruptions to relate specific dermatomes to an affected nerve root.13 From this data, they created the first accurate map of human dermatomes.

Rivers, the remarkable Renaissance man, made many valued contributions as an experimental psychologist, anthropologist, and experimental neurologist. His work on symptoms induced by trauma was the foundation of PTSD. He justly earned lavish praise from his many shell-shocked patients, perhaps all the more notable because he systematically minimized his own poor health.

References

- Head H. Obituary notice of William Halse Rivers Rivers. Proc Roy Soc, 1923; 1-5.

- Seligman CG. Obituary: Dr W H R Rivers The Geographical Journal 1922;60, No 2:162-163.

- Myers CS. ‘A Contribution to the Study of Shell Shock’, The Lancet 1915;185, 4772:316–20.

- Turner WA. Remarks on Cases of Nervous and Mental Shock. British Medical Journal 1915;1, 2837: 833–835.

- Oppenheim H. Die Traumatischen Neurosen 2nd ed Berlin, Germany: Hirschwald 1892.

- Rivers, WHR. War Neurosis and Military Training (1918) In: Madness to Mental Health ed. Eghigian G. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2010 pp. 238-244.

- Soleil Shah. WHR Rivers and the humane treatment of shell shock Hektoen International Spring 2019.

- Rivers W H. “The Repression of War Experience” The Lancet 1918; 194: 173-4.

- Wilson JM. Dr W. H. R. Rivers: Siegfried Sassoon and Robert Graves’ ‘fathering friend’. Brain 2017;140:3378–3383.

- Bartlett FC. William Halse Rivers Rivers 1864-1922. The American Journal of Psychology 1923;34:275-277.

- Horowitz M. Stress response syndromes Archives of General Psychiatry 1974;31:768–781.

- Summerfield, D. The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category BMJ 2001;322:95-98.

- Head H. The grouping of afferent impulses within the spinal cord Brain 1906;29:537-54.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Psychiatry & Psychology

Leave a Reply