Stephen Martin

County Durham, UK

|

| Fig 1. Durham Cathedral, gate of Benedictine Priory, exterior, built by Prior Castell, 1494-1519. Photo © author, 2021, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

County Durham in the northeast of England is rich in the atmospheric remains and documented history of medieval hospitals, all connected with the church. Looking at the whole group has some interesting new lessons.

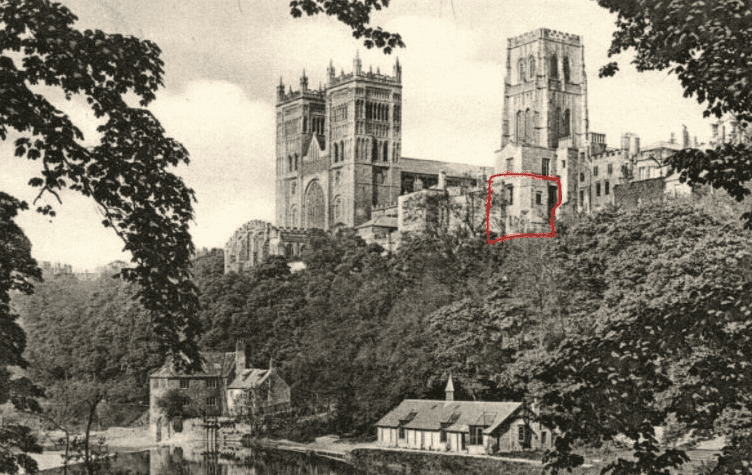

Durham Cathedral

Durham City’s Benedictine Priory, later the Cathedral, ran two infirmaries.1 One, for “lay folk,”2 with its own chapel, stood outside the monastery gate.3 (fig 1) The lay infirmary was probably opposite, overlooking the River Wear to the east. Half of this “infirmary without the abbey gate” had been “erected from the ground,” costing £13 10s in 1338.4

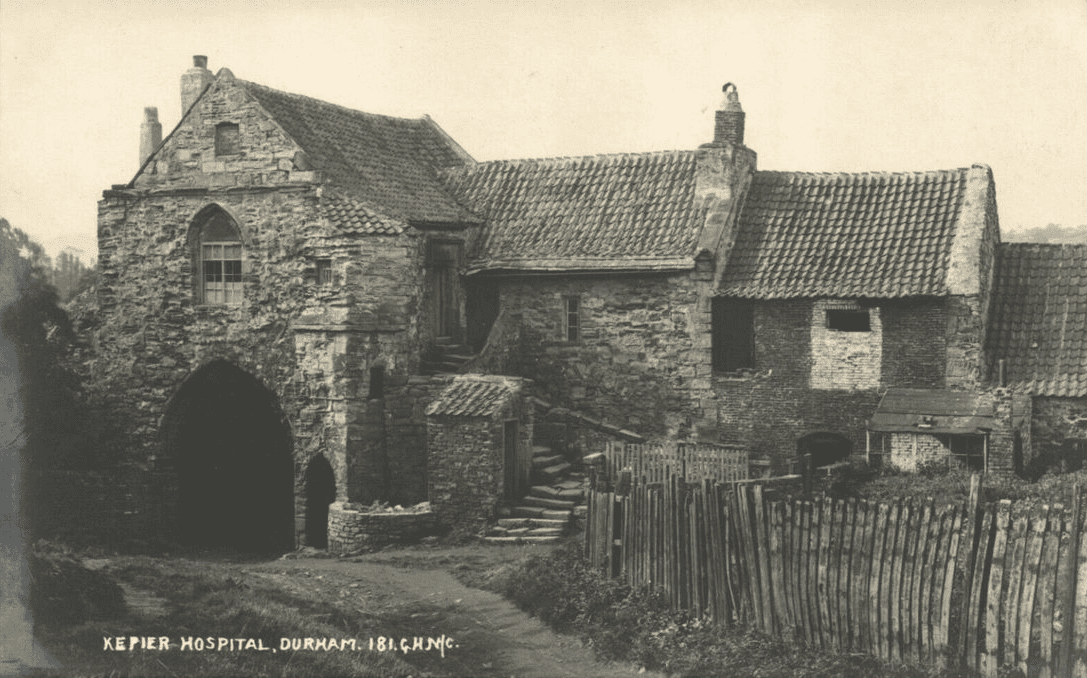

The monks’ infirmary was in the southwest of the monastery precinct,5 also high above the river.6 (fig 2) Between 1419-1430, £400 was spent on the monks’ infirmary.7 Massive buttresses (fig 3) stopping it from falling in the river look like part of this costly work.8 Besides names, archive details are scant, but we know if a monk died his belt went to the “Infirmarer.”9 Around 1301, John of Barnard Castle, monk and Priory Almoner, was imprisoned by besieging Northumbrian troops “despite being gravely ill in the infirmary.”10 Henry VIII dissolved Durham Priory on 12 May 1541,11 ending the infirmaries and some hospitals.12

|

| Fig 2. Durham Cathedral. Possible surviving portion of original monks’ infirmary walls highlighted. Valentines Postcard Series, c. 1904. Author’s collection ©, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

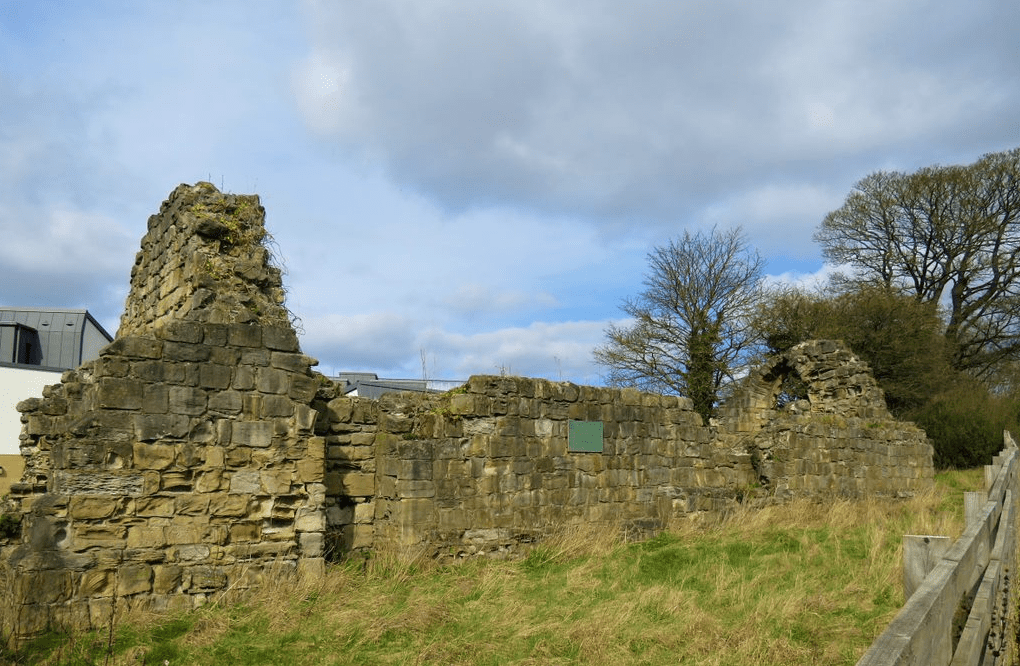

Kepier Hospital, Durham City

The hospital gatehouse (fig 4) from the 1300s is still standing north of the city. Surtees noted that it was founded in 1112 by Bishop Flambard for “the support of the poor who shall abide in the hospital house which I have provided,” in part dedicated for the “redemption of the souls” of his first patron William the Conqueror and Queen Maud. The original hospital was apparently burned by the Scots around 1140 and rebuilt near the river at Kepier. St. Giles was its dedication and associated place of worship, now the parish church.

Hospital of St. Mary Magdalen, Durham City

The Almoner ran Magdalen Hospital for “thirteen good men and women who had seen better days.”13 It probably stood east of the current chapel ruins, though ruined walls join the west exterior. That there were in-brethren, out-brethren, and sisters implies staff supported and cared for the infirm, not just running a hostel for the impoverished. Bishop Skirlaw in 1391 referred to “the support of the poor.” The site moved uphill and a new chapel (fig 5) was consecrated in 1451, with 15s 1d spent on a fresco of Mary Magdalen.14 The hospital made money from cattle, running a tan yard making belts and boots and producing beef, milk, and cheese commercially. Kepier and Magdalen faded away post-dissolution.

|

| Fig 3. Site of Durham monks’ infirmary today, west river bank, with surviving massive buttresses (inset), c. 1420, indicating the seriousness of medieval hospital management. Photo © author, 2021, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

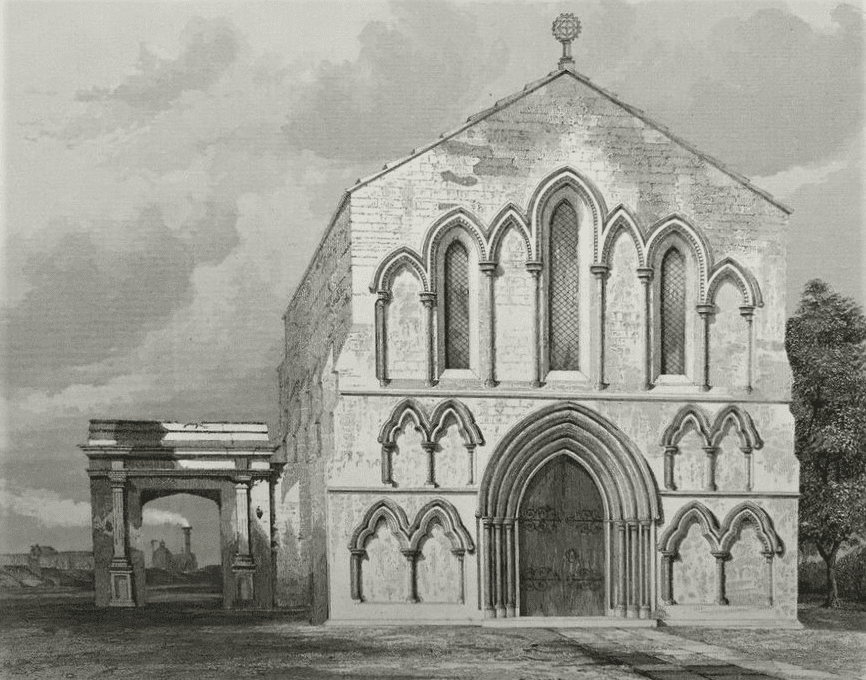

St. Edmund’s Hospital, Gateshead

The origins of this hospital are a mystery. Henry VIII’s agents noted the records no longer existed.15 Again, income was from farming.16 After the dissolution, part of the hospital became a private residence, Gateshead House. The hospital still functioned in 1810, with a “master and poor brethren” when the Bishop of Durham planned expansion. In 1837, John Dobson restored the medieval chapel17 (fig 6) for worship. It was extended northwards in the 1890s.18 The Elizabethan entrance was placed in the precinct south wall of the surviving medieval chapel, where it still stands.

Putative monastic infirmaries

Archaeologist Rosemary Cramp argued that the sizeable monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow had infirmaries.19 The putative site at Wearmouth was covered by ballast tips downhill towards the River Wear. Jarrow’s may lie south of the main buildings next to the River Don. Finchale Priory, prettily situated on the Wear just downstream from Durham City, was also large enough to have warranted an infirmary. East of the Abbot’s lodging is the likely riverside site, where wall remains lack evidence for clear use.20

Greatham Hospital, Hartlepool

Greatham not only still exists, but still offers residential and day care. Founded by Bishop Stitchill on the Morrow of the Epiphany of 1272, the dedication, then as now, was to God, St. Mary, and St. Cuthbert. The medieval staff were exempt from taxes or legislation, except for causing loss of life or limb. The most infirm were allowed to miss church services and pray in bed.

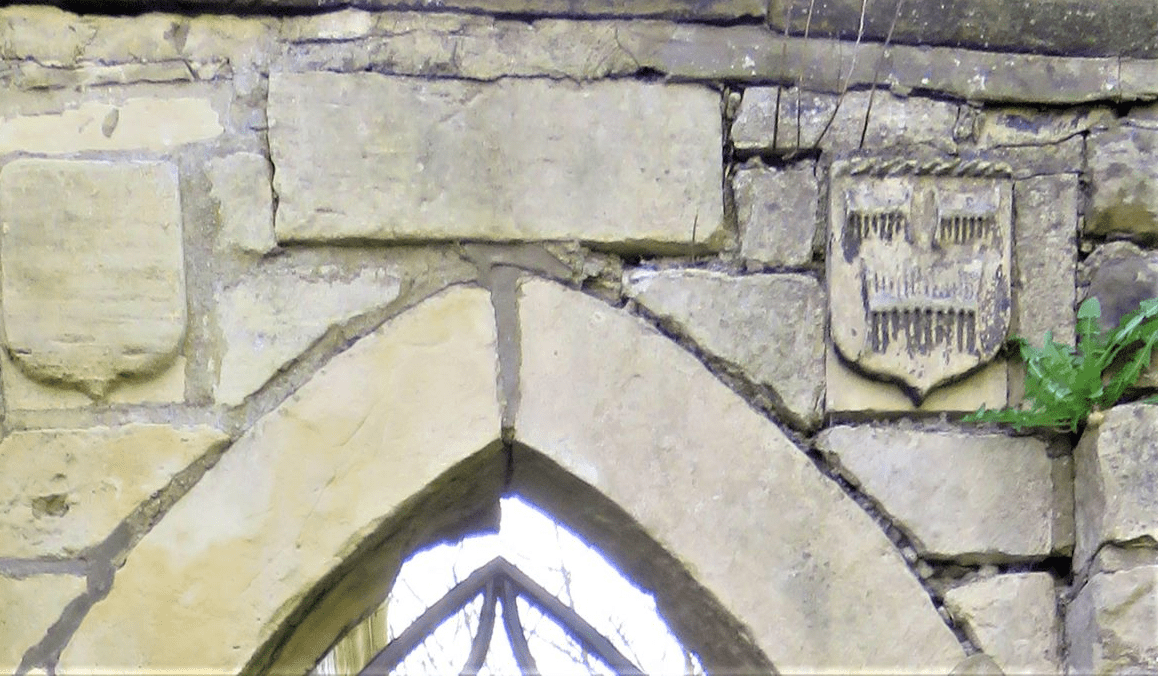

The early chapel and housing have gone (fig 7), but for some good Tudor heraldry21 (fig 8) of Cuthbert Tunstall (1474-1559), Bishop of Durham under Henry VIII and Edward VI.22 His arms have combs because his ancestor was William the Conqueror’s barber. The upper two one-sided combs match the design in other versions with central holes for hanging them up. The lower Greatham comb resembles the Anglo-Saxon one, by then removed from St. Cuthbert’s coffin, with its double-sided teeth. It is larger than Tunstall’s usual combs, symbolizing the power of the Saint. We do not know if Mr. Tunstall of the conquest was William’s barber surgeon or super-specialized in hair cutting.

|

| Fig 4. Kepier’s surviving gatehouse and attached wing suggests a large hospital, comparable in size to Sherburn, for which bed numbers are known. Photo c. 1900, © Author’s collection, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

The hospital survived the dissolution and was re-founded in 1610, reflecting population decline and growth after the Black Death of 1349-50. The Regency architect Jeffry Wyatt rebuilt the hospital in 1803-1804, echoing the arches of the blocked medieval arcade, but in lancets rather than the rounded Norman style. This Gothic revival style had a clever logic to lancets post-dating curved arches. (fig 9)

Sherburn Hospital, near Durham City

This is another staggering survivor, still admitting well into its ninth century. It began in 1181 as a “lazar house” for sixty-five leprous monks and nuns.23 They were well fed with allowances of bread, ale, meat, fish, cheese, and butter, besides receiving shoes and grease. One old woman tended the sick, who got fuel and candles. We will never know her exact duties, but there is a tantalizing clue from York’s monastic infirmary. This is a reference from AD 1276 to Anna of York Medica,24 suggesting that she was working as a physician. A Christiana is also mentioned in Jarrow in AD 1313, though without any descriptor.25 Interestingly, Anna and Christiana both predated the Black Death, whose depopulation depleted the work force for centuries and must have restricted women’s opportunities beyond basic labour. Durham’s population had still not recovered by Henry VIII’s time.

The original chapel survives. Handsome, like an early parish church, the squat tower has atmospheric blind-lancet arcading and three original Norman arched windows. Hospital precincts had superb architecture.26 (fig 10)

|

| Fig 5. Magdalen Hospital Chapel Ruins, Durham City. Photo © author, 2021, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

Discussion

We do not have a good estimate of the population of medieval County Durham, but we do for the City; Russell suggested 2,000 inhabitants in AD 1200,27 with a probable static population after AD 1250.28 We know of thirteen beds in Magdalen and sixty-five at Sherburn. With conservative estimates of beds in Kepier and the two Cathedral infirmaries, the total was about 150, suggesting beds for 7.5%.

Recent data shows that the UK has 714,000 beds for health and social care, for a population of 66.5 million, indicating 1.1% occupying them.29 There were probably more hospital and social care beds per capita for medieval Durham City than there are now in the UK. Although those with money and families were not admitted to some hospitals, there might have been an order of magnitude more beds. People aged faster from harder labor, but this was accommodated.30

The neighboring North Riding of Yorkshire was rich in medieval monastic infirmaries.31

Nearby Newcastle upon Tyne had so many monasteries that its pre-conquest name was Monkchester. County Durham had few monasteries, due to its powerful Priory controlling lots of land. That power was originally from William the Conqueror’s firm stamp on the rebellious North, but it influenced hospital survival.

|

| Fig 6. St. Edmunds Chapel, Gateshead, in Durham. The ruined Elizabethan entrance is to the left. The chapel still stands, presenting a dignified facade of blind trefoil and interspersed lancet arch arcading. R. W. Billings, engraved by G Winter, in The Architectural Antiquities Of The County Of Durham, Ecclesiastical, Castellated, And Domestic. George Andrews, 1846. © Author’s collection, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

Durham’s well-meaning post-reformation bishops kept close links to peripheral hospitals. Whilst Henry VIII removed cash, treasures, and superstition, he did not keep on taxing Durham Cathedral and allowed the Prebend Canons he appointed to control estate rents.32 Henry was not out to vandalize the whole operation or maximize long term personal gain. He kept some positive philosophy throughout his crises of church politics, divorce, and repeated brain insults.33 As a young man, Henry composed Pastime with Good Company and played recorders from his collection of eighty instruments. The nice traits of his premorbid personality appear to have given the church freedom to allow the survival of some hospitals.

It is notable that the candidate sites of the monastic infirmaries in Jarrow, Wearmouth, and Finchale, alongside Durham’s, are as close as possible to rivers. Both the monks’ and lay infirmaries in Durham were high above the Wear. Durham has a strong updraft from the river, giving buildings good ventilation.34 These were pleasant therapeutic settings, but the waterside theme and ventilation imply Galenic ideas. Ventilation countermanded malaria in the elemental philosophy of air imbalance. Water was Galenic. At Fountains Abbey in North Yorkshire the infirmary was surprisingly built over the River Skell. Air (blood) balanced earth (black bile, melancholy). Water (phlegm) balanced fire (yellow bile, hepatic irascibility); quite psychiatric.

Medieval hospitals had wide functions, reflecting medical and social care today in terms of old peoples’ homes, ambulant or resident welfare for poverty, leprosy,35 sickness, and frailty. They were homes and places of support as much as hospitals. Although there were lulls from marauding forces and plague, both Greatham and Sherburn have a breath-taking endurance of well-run elderly care over many centuries.36

Farms around hospitals are not the modern answer to revenue. Today they would have to draw agricultural subsidy. Charges for parking under private finance initiatives are not effective and pleasant income sources like medieval sheep and cattle. Therapeutic mental hospital farms were sold recently for housing land; once those assets had gone, they had gone. Hospital chapels, strongly-vaulted gatehouses, and colossal buttresses have survived many centuries from robust construction. How many hospitals built in the last two decades will have any fabric left, even by the end of this century?

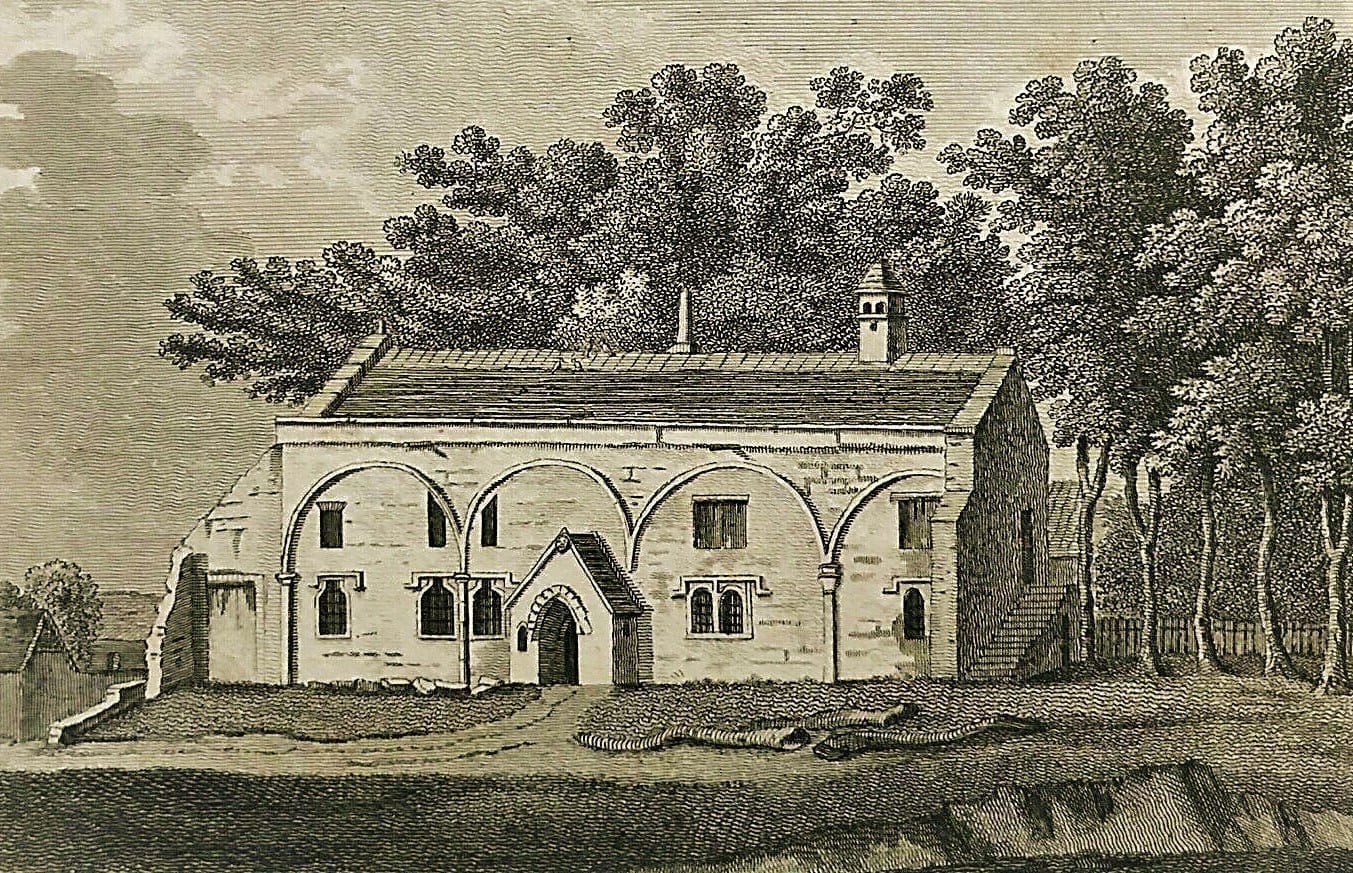

|

|

| Fig 7. Medieval Greatham Hospital in 1785. Note the logs as fuel to warm the patients. Engraved by Samuel Sparrow, in Gross F. The Antiquities of England and Wales. Hooper, London, 1772-1787. Photo © author from personal collection, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. | Fig 8. Arms of Bishop Tunstall, Greatham, early 1500’s, rebuilt into 18th-century walling. Photo © author, 2021, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

|

|

| Fig 9. The lovely gothic-revival rebuild of Greatham Hospital today, 1803-1804, by Wyatt. Photo © author, 2021, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. | Fig 10. Sherburn Hospital gatehouse exterior, medieval. Photo © author, 2021, permission for academic & non-commercial reuse. |

End notes

- Page W, Ed. Durham Cathedral: Monastic Buildings. History of the County of Durham. Vol. III. Victoria County History, London, 1928, pp. 123-136.

- Lay brothers were monastery staff who were not ordained monks. Lay folk (See Surtees, below) means the general public.

- Rites of Durham. Surtees Society, Durham, London and Edinburgh, 1902, no. 107, p. 272.

- Almoner’s cartulary, Status 1338, The College Library, Durham University Library Archives and Special Collections. Discussed in the seminal work: Cambridge E. The masons and building works of Durham priory, 1339-1539. PhD thesis, Durham University, 1992.

- This is between the monks’ dormitory and guest house area. The Priory had up to 100 ordained monks.

- It flows both east then west of the cathedral around a beautiful tree-lined meander, a site no doubt chosen for defence and exhilaration. The tradition is that monks carrying St. Cuthbert’s coffin followed a cow girl to the site, but they knew where they were going.

- Raine, J. (Ed.), 1839. Historiae Dunelmensis Scriptores Tres. Gaufridus de Coldingham, Robertus de Graystanes, et Willielmus de Chambre. (Surtees Soc., IX) 1839, App., cclxxiv. Discussed by Cambridge, op cit.

- The huge surviving construction in selected, insoluble stone fits this expense. Like the lay infirmary bill, typical small building repairs of the time were orders of magnitude less. Cambridge, op cit, pp.103-104, suggested the link between the bill and the buttresses.

- Durham University Library Archives & Special Collections Catalogue. Durham Cathedral Archive: Almoner’s Small Cartulary. GB-0033-DCD-Alm-Sm-Cart, p. 77. Good belts were worth several shillings at the time, according to theft valuations in cathedral records.

- Durham University Library Archives & Special Collections Catalogue. Durham Cathedral Archive: Locelli. GB-0033-DCD-Loc. Loc. VII: 4. As the Almoner monk, he had run mills and estates supporting the hospital. Hospitality was prominent in the Code of Saint Benedict.

- After this dissolution Henry appointed only twelve monks as Cathedral Prebends, including nine from the Priory along with their Prior as the new Dean. See: Horn J M, Smith D M, Mussett P. Durham: Introduction. Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae 1541-1857: Volume 11, Carlisle, Chester, Durham, Manchester, Ripon, and Sodor and Man Dioceses, London, 2004, pp. 67-69.

- Further research might explain exactly how and when they stopped functioning. We cannot prove they disappeared straight away at the dissolution, but it appears that records do cease then. Sherburn possibly took over with less leprosy, low population, and the simultaneous decline of Magdalen and Kepier.

- Discussed by Surtees. Admissions were on pain of forfeiture for adultery or fornication. The Almoner’s small cartulary has several examples of this clause. That apart, unsupported people with learning disability and mental illness may have used Magdalen. The Almoner also ran a Magdalen Hospital branch for four lepers at Witton Gilbert, west of the City, named after its founder Gilbert de la Lay in 1154. (See Pevsner) The few records stop before the dissolution. A lovely window, we think of 1250-1300, survives in Witton Gilbert Hall, which developed around this hospital, illustrated in: http://historicengland.org.uk

- Clay R M, Ed Cox C. The Mediæval Hospitals of England. The Antiquary’s Books. Methuen and Co, London, 1909.

- See Surtees, and: https://englandsnortheast.co.uk/medieval-gateshead/

- From land nearby and remotely at Shotley Bridge, with annual income at the dissolution of 109 shillings, 4 pennies.

- It is now Holy Trinity Church.

- Pevsner N. Williamson E. The Buildings of England, County Durham. Penguin Books, London, 1983.

- Cramp R. (Ed) Wearmouth and Jarrow Monastic Sites, Vol 1. English Heritage, 2005. Bede died in his own cell at Jarrow in AD 735, leaving his colleagues his pepper, linen, and incense.

- We are currently researching a lost leper hospital in the south of the county with a tenuous link to Finchale.

- Sable (black), three combs argent (silver). The current chapel was built in 1788 (Pevsner).

- Surtees noted a plan for Bishop Tunstall to visit Greatham in 1532.

- Gibby C W. Sherburn Hospital. Sherburn Hospital Governors, 1981. Also Pevsner op cit, Clay op cit, and: https://sherburnhouse.org/about-us/our-history/ The restrained current lodgings are from c. 1760, with a heavily-Victorian main building.

- Hospital Ordinance, 1276, discussed in Historians of the Church of York. Vol.3, p.203.

- Cullum P H. Hospitals and charitable provision in medieval Yorkshire, 936-1547. D. Phil. Thesis, University of York, Department of History, September 1989, p. 165.

- Esteem in nice surroundings is of proven value in modern rehabilitation. Sherburn chapel is well-illustrated at: http://historicengland.org.uk

- Russell JC. British medieval population. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1948.

- Camsell M. The development of a northern town in the later middle ages: the City of Durham, c. 1250-1450. Volume I. D. Phil. Thesis, University of York, Department of History, 1985, p. 7. This is the seminal work on medieval Durham City.

- https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/nhs-hospital-bed-numbers. Updated 2020. Also drawing on UK social care data and published Welsh, Scottish, and Northern Irish national figures.

- Even at double the population and half the beds we estimate, it is still twice today’s percentage. You could retire into the Cusanus Stift hospital of the Moselle valley at age 50, in 1451.

- Infirmary ruins survive at Rievaulx, Fountains, Jervaulx, and Easby. Byland Abbey also had an infirmary. In AD 1280 the Archbishop of York documented that canons at Guisborough were feigning illness to be cared for in the infirmary.

- Some of their families still ran Cathedral property into the early twentieth century.

- He appears to us to have had an organic personality disorder, meaning with coarse physical brain change, from two accidental insults; a traumatic brain injury jousting and a lesser-known asphyxiation on sport pole-vaulting across a marsh, when he needed resuscitating. Brewer, C. The Death of Kings: A Medical History of the Kings and Queens of England. Abson Books, London, 2000.

- The original geology was a deep limestone gorge, quarried back for stone to build the Cathedral. The Almoner grew fruit on the sheltered new terraces to fund Magdalen Hospital.

- For a good overview see: Pearce J M S. Leprosy: A nearly forgotten malady. Hektoen, Summer 2018. https://hekint.org/2017/12/29/leprosy-nearly-forgotten-malady/

- Church links endure too. Sherburn admits retired clergy and retains a chaplain. Greatham still has senior clergy as trustees.

Further reading suggestion

Surtees R. The History and Antiquities of the County Palatine of Durham. Nichols, Son, and Bentley, 1816-1823. Republished by E P Publishing, 1972. Vols I – section on Sherburn Hospital, II – sections on Monk-Wearmouth and Gateshead, III – section on Greatham, IV – sections on Durham City. This great work of Robert Surtees (1779-1834) is important historiographically, covering lots of primary sources behind this article 200 years ago.

STEPHEN MARTIN, MB, BS, Newcastle upon Tyne, dedicates this article to his father, Bernard Martin, an inspiring medievalist who sadly succumbed to Covid. “Education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another.” G K Chesterton.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply