Stephen Martin

United Kingdom & Thailand

Aidan Jones

United Kingdom

|

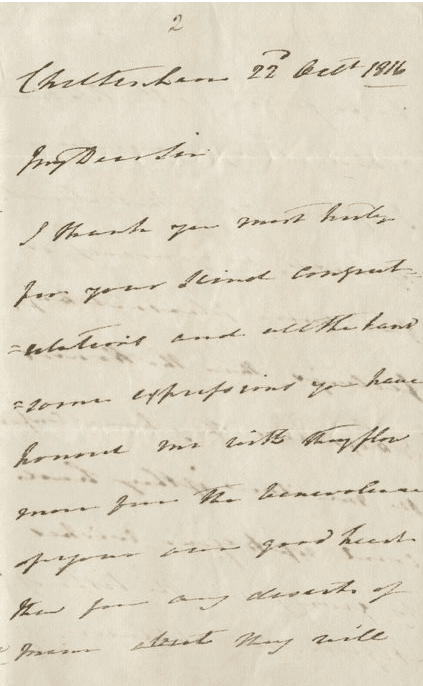

| Opening section of letter. Photo © Cat Ring Books, Amherst, Massachusetts. |

A revealing, unpublished letter was written by Edward Pellew two months after commanding the Bombardment of Algiers to suppress Mediterranean slave traders. Short, sensitive, and emotional, it is an insight into the psychology of a great battle commander and anti-slavery leader. The surrounding events, stresses, and relationship dynamics are remarkable.

Pellew’s letter

Unmistakably in Pellew’s hand, the letter was written in Cheltenham on 22 October 1816, (Fig 1) just over a fortnight after his return to England.1 He was responding to a letter sent to him from a colleague about to go to Madras and was forwarded to his Cheltenham lodgings, where he went with his wife soon after the battle. They had previously gone there in 1814 “to take the waters,”2 following his earlier Mediterranean anti-slavery service.

The letter must have been addressed to Major General Edward Gwatkin, 1784-1855, as it came from a Gwatkin family album3 begun by his parents, Theophila and Robert. The album remained in his family, having items post-dating their deaths. Edward Gwatkin served in India for over fifty years; Robert never did. The letter went unidentified in the sale catalog and is a single sheet with a fold, comprising four pages of handwriting:

My Dear Sir,

I thank you most humbly for your kind considerations and all the handsome expressions you have honoured me with. They flow more from the benevolence of your own good heart than from any deserts of praise about. They will be forgotten as the less cherished in my remembrance. I assure you that sentiment of words as yourself is far more pleasant to my feelings than the numerous indignities they have conferred on me. Know if they had come up to your wishes by giving me the title of Algiers. The applause of great men and of my country, with an approving conscience are far more estimable in my view than all the honours Sovereigns can bestow.

I was receptively sorry my friend Penrose did not arrive 48 hours sooner. He knew the localities and worked often dejected our plan went under under. (sic) I know I should have found him just where I wished him to be and I love him too much not to share in his mortification, as he knows that I do.

Pray do offer my best wishes with Lady Exmouth to the gracious Munro family. I hope my friend at Madras goes on well.

I am, my Dear Sir, with high & servient esteem, your obliged and faithful servant

Exmouth

|

| Edward Pellew (1757-1833), as a young officer in naval undress coat without epaulettes, 1790’s. With his receding curls, blue eyes, aquiline nose, and well-nourished face, he looked tough and rustic, not quite the Hornblower image. Oil on canvas, anon. © UK private collection, permission for non-commercial re-use. |

Accolades and mental mechanisms

Pellew had wished for a title reflecting the site of his victory, resembling “of The Nile” attached to Nelson’s baronetcy and later retained in the title of Viscount in 1801.4 His wish drew on his pride in the task, and an ambitious level of recognition for courage in a cause. He was already signing Exmouth as a Baronet from 1814. The House of Commons had approved the title of Viscount Exmouth on 27 August 1816, but they disallowed him adding “and Algiers.”5 His disappointment in not getting it was clearly marked, forming the psychiatric hub of this article. Pellew could be very blunt and as a younger officer (Fig 2) he had been particularly at odds with William Pitt; his title was at the mercy of a political decision.6

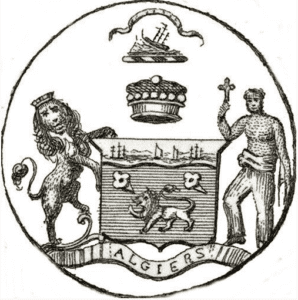

It was easier for him to receive all of his desired accolades as a Viscount, unchallenged, from the College of Arms, with his flagship HMS Queen Charlotte and Algiers on the shield. (Fig 3) The version shown also has the single-sailed rocket barges that were a crucial part of his strategy. Algiers in capitals on the mount terrace, shown in this version as a motto, could not be a plainer statement, with the freed slave supporter. Pellew was no stranger to fame for his courage in leading a rescue from the ship Dutton, standing on its deck, when it went aground at Plymouth in 1796. The wreck of the Dutton forms the crest of his Arms.

He monitored his accolades and valued the addressee’s personal and insightful praise. He played down vanity in minimizing international honors, writing with obvious genuineness and conscience. That is also borne out in his comments empathizing with Rear Admiral Sir Charles Penrose, who was late for the battle, and Pellew hinted at dangerous consequences from that flaw in his plan.

Cyril Northcote Parkinson, best known for his history around Forester’s Hornblower novels, analyzed Pellew’s post-battle correspondence in 1934, writing as a Cambridge post-doctorate historian.7 Pellew wrote to Lord Sidmouth from Portsmouth on 6 October 1816:8 “I wish our good citizens of London may be as satisfied with me as I am with myself.” He wanted recognition and to share a sense of achievement. Pellew had written to Sidmouth on 29 August 1816,9,10 two days after the bombardment, regretting “the sad loss we have sustained” and shadowing his regrets in the letter. He balanced this feeling with “we were exposed to a complete circle of fire,” and “I consider this the happiest point of my fortunate Life. 1000 slaves are now cheering on the mole . . .”

|

| Pellew’s coat of arms as Viscount Exmouth. Detail, print, unknown Regency book frontispiece, author’s collection, permission for non-commercial re-use. |

The action had freed seven times the number of slaves than men lost in Pellew’s fleet. Next, on writing to Sidmouth, Pellew said Algiers was soon afterward preparing for a potential future American attack: it never came. The strength of American public conscience in Mediterranean slavery is relevant. The Battle of Derna, now in modern Libya, was fought by the United States Marines in 1805, one of two American anti-slavery campaigns in the Mediterranean prior to the Bombardment of Algiers. Pride in the anti-slavery efforts was written into The Marines Hymn, still very famous today with “to the shores of Tripoli.”11 The lyrics were late nineteenth-century.

To write the word under twice in the letter was probably because of fatigue or distraction. Such a language pattern, called perseveration, occurs occasionally in frontal head injuries, a real risk in Regency sailors. An obsessively repetitive connotation of failure and demise with the idea of sinking and drowning, is another reasonable psychodynamic interpretation.12

Friends and personality traits

Pellew’s character judgment of the Munro family and his friendship with them are notable. Being in Madras, his description only fits Sir Thomas and Lady Jane Munro. (Fig 4) The presence of a whole family out in India implies seniority, which narrows the field. Sir Hector Munro and his four children connected with India had all died before 1816. There were no other Munro family candidates in Madras at the time.

Lady Jane Munro was recognized as a high-caliber individual.13,14 She was in Madras with her husband, Sir Thomas Munro, from 1814. With Jane’s support, he reformed the judicial system enhancing village-based magistracy powers15 and conducted a survey of Indian children in schools.16 That highlighted religious differences in pupils and the fact that Indian girls were attending school at only 1% the number of boys. The absence of documents on Jane’s activity as a British woman in India is typical for the time; what is known of her remains consistent with intelligent, lasting, and effective input. Thomas Munro was already working in colonial Madras on improving the judiciary with local Indian magistrates in 1816.

Pellew’s letter matches character traits highlighted by Stephen Taylor,17 who has given Pellew’s personality the most complete and up-to-date scholarly attention. Listing Taylor’s examples afresh, he noted interpersonal warmth,18 generosity,19 and romanticism.20 There were more examples of humane altruism21 in Pellew than any other trait. Arguably, all of those elements were shown in the Cheltenham letter, along with his occasional feelings of inadequacy, also brought out by Taylor.22 Insecurity is normal and essential in leadership to monitor risk. Concealing it to the extent that others do not use it against you is vital. In this letter, Pellew only let his guard down to a particular confidant.

Another example of Pellew warming to people with a reforming conscience was his friendship with the liberal William Bentinck.23 He finally banned women’s suttee suicide in India after years of horrible legality, which the government had struggled to supervise. That bond further clarifies Pellew’s character.

Discussion

Pellew’s civil tone reveals the motivation for his recent action against slavery to be humanitarian and altruistic, not narcissistic. Getting the authority to carry out the action had been an uphill struggle. He was a professional military man with a moral conscience. There is no suggestion of flawed personality in his psychological drive for recognition. The American Psychiatric Association’s DSM-V diagnostic criteria for any personality disorder certainly do not apply to Pellew. His behavior was pro-social, not anti-social. Algiers was not fought for Pellew’s material profit. He wanted specific recognition and a memorial to his cause.

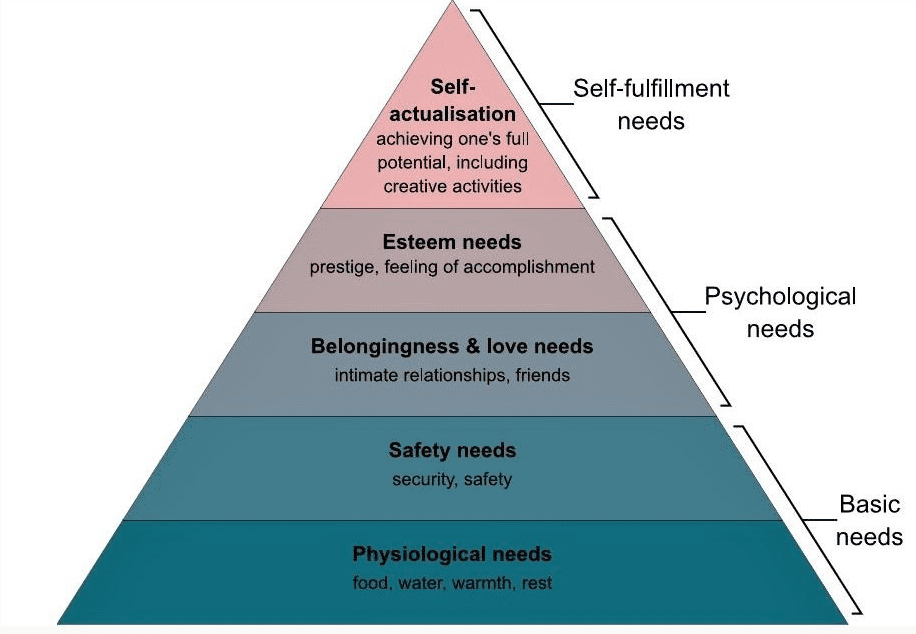

Abraham Maslow24 remains widely respected many decades on from publishing in his hierarchy of needs that self-actualization, including people’s high evaluation of themselves and their esteem, are basic satisfactions. (Fig 5) Pellew was happy with his achievements. It is too easy to be disdainful of success and to dismiss a right to recognition as showing off. Emphasizing Penrose’s delay relates to what was, at least, an unconscious sense of risk and uncertainty in the conflict. Bravely overcoming that allowed a military challenge against the slavery states of North Africa after they ignored diplomacy. The letter also highlights Pellew’s circle of friends, reflecting his own altruistic character trait. Considering character and mental mechanisms with a forensic psychiatric eye is valuable in history, yielding nuanced lessons and helpful truths, even from a simple letter.

|

|

| Lady Jane Munro (1795-1850) in a velvet dress, resembling the robes of a baronet, by Sir Martin Archer Shee PRA, 1769-1850. Oil on canvas. Reproduced with the kind permission of the National Portrait Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND. | Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Source Wikimedia, CC-BY-SA 4.0. |

End notes

- The action was on 27 August 1816. Pellew had reached Spithead from the Battle of Algiers on 5 October 1816. He wrote to the Admiralty from Portsmouth on the 6th and the flag was struck on the 8th. He arrived in London on 9 October 1816.

- Fremantle papers, letters sent and received, 1814. Pellew to Fremantle 27.8.14. Archives of Royal Museums Greenwich. Cat ref D/FR/32/7.

- Gwatkin T. Autograph Album, early nineteenth century. English Literature, History, Children’s Books and Illustrations sale. Sotheby’s, London, 10 December 2019. Cat ref Lot 12.

- Mahan A T. The Life of Nelson. Little, Brown and Co, Boston, 1899, pp. 600-602: Nelson had wanted to attack Mediterranean slave traders but was banned from doing so, due to agreements on the use of North African ports during the Napoleonic wars. In 1799, responding to slavers kidnapping Sardinians, he wrote “My blood boils that I cannot chastise these pirates.”

- Perkins R, Douglas-Morris K. Gunfire in Barbary. Admiral Lord Exmouth’s Battle with the Corsairs of Algiers in 1816. Kenneth Mason, Homewell, 1982, pp. 165-166. Discussion and transcript of House of Commons proceedings.

- Interestingly, even William Wilberforce himself passively declined to become involved in campaigning against Mediterranean slavery.

- Northcote Parkinson C. Edward Pellew, Viscount Exmouth, Admiral of the Red. Methuen and Co Ltd. London, 1934.

- Political and personal papers of Henry Addington, 1st Viscount Sidmouth, 1705-1824. 6.10.1816, letters from Pellew to Lord Sidmouth. Devon Heritage Centre, Devon Archives and Local Studies Service (South West Heritage Trust). Cat ref 152M/C/1816/ON.

- Sidmouth papers, Op. cit., item of 29.8.1816.

- Northcote Parkinson, Op. cit., p. 466.

- Marines Hymn, second line, US Marine Corps authorized version, 1929.

- Manneristic repetition, of an initially purposeful word, is more common when spoken (palilogia) than when written (paligraphia). It can occur in Tourette’s Syndrome. Head injury in Marines today continues to be researched.

- Gleig GR. Life of Munro. Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley. London, 1830. Vol 1, p. 401. Gleig described her as “accomplished . . . a lady remarkable for the correctness of her manners and steadiness of her principles, nothing could have befallen more fortunate or more beneficial in its general consequences.” Thomas Munro wrote to her from Madras, 16 May 1826, Gleig Op cit, p. 361: “I do not see what use either you or I can be of any longer in this country.” She had clearly been effective and involved, albeit with slow progress.

- Stephen L (ed). Dictionary of National Biography. Smith, Elder and Co, London, 1894, 39, under Munro, Thomas. Not expanded in later editions.

- Beaglehole T H. Thomas Munro and the Development of Administrative Policy in Madras 1792-1818. Cambridge University Press, 2010. Thomas Munro is still held in extraordinarily high regard by present day Indian politicians and academics. Sriram Venkatakrishnan wrote, “Munro was of a rare breed – a genuine friend of the Indian. His death was, therefore, the occasion for universal grief in the Madras presidency.” (https://sriramv.wordpress.com) He also noted in The Hindu, 26 July, 2010, “. . . the state administration could think of translating his statements into Tamil . . . Successive generations can then know of the requisites of good administration and also realise that all colonial masters were not evil.” Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, the first Indian-born Governor General and leader of the Indian National Congress said, “Whenever any young Civil Servant came to me for blessings or when I spoke to them in their training school, I advised them to read about Sir Thomas Munro, who was the ideal administrator.” K N Jayaraman wrote, “. . . there were, indeed, countless British administrators who had a soft corner for the Indian natives. Many of them worked hard and gave no room to corruption and under-handed dealings . . . Sir Thomas Munro was a humane and effective administrator.” (navrangindia.blogspot.com)

- Bharathy R. Sir Thomas Munro’s Minute on education – Its Effects. Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. Vol. 61, Part One: Millennium (2000-2001), pp. 1005-1010.

- Taylor S. Commander. The Life and Exploits of Britain’s Greatest Frigate Captain. Faber and Faber. London, 2012.

- Taylor, Op. cit., pp. 168, 185, 232

- Taylor, Op. cit., pp. 72, 88, 166

- Taylor, Op. cit., pp. 95

- Taylor, Op. cit., pp. 95, 195, 216, 225, 294

- Taylor, Op. cit., pp. 214, 227, 229

- Correspondence from Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth, to Lord William Bentinck, 1816-1825. Nottingham University Library, Department of Manuscripts and Special Collections. Cat ref Pw Je 619-652.

- Maslow A H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychological Review, 1943, vol 50, pp. 370-396. He wrote this in Brooklyn College: “All people in our society (with a few pathological exceptions) have a need or desire for a stable, firmly based, (usually) high evaluation of themselves, for self-respect, or self-esteem, and for the esteem of others.” He studied with Sigmund Freud’s colleague, Alfred Adler, and described “sick and healthy halves of psychology” as complementing Freud.

Acknowledgments

The letter facsimile reproduced here, and this first transcript with interpretation, are allowed with the kind written permission of the owner, Cat Ring Books, Amherst, Massachusetts, with no conflict of interest. We thank Surgeon Lt. Commander Duncan Veasey FRCPsych RN (Ret’d) and Ed Martin PGCE BA (Hons) for their scholarly comments.

STEPHEN MARTIN is Honorary Professor of Psychiatry at Chiang Mai Medical School and a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

AIDAN JONES, PhD is a neuropsychological Medicolegal Expert working in the British Courts and was Head of Service & Consultant Lead for neuropsychological rehabilitation in Oxford.

Spring 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply