Enrique Chaves-Carballo

Overland Park, Kansas, United States

|

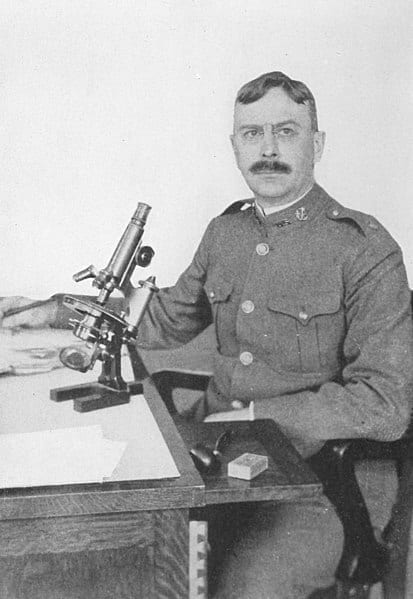

| Charles Wardell Stiles (1867-1941). Parasitologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Portrait ca. 1912. Wikimedia Commons |

Rockefeller Foundation

The Rockefeller Foundation was chartered on June 1909 “to promote the well-being and to advance the civilization of the peoples of the United States and its territories and possessions and of foreign lands in the acquisition and dissemination of knowledge, in the prevention and relief of suffering, and in the promotion of any of the elements of human progress.”1 One month later the first major subdivision of the philanthropic empire, the International Health Commission, was established for the main purpose of eradicating hookworm disease, a scourge that “prevails in a belt of territory encircling the earth for thirty degrees on each side of the equator, inhabited according to current estimates by more than a thousand million people.”2

Charles Wardell Stiles

Charles Wardell Stiles, a zoologist and public health official at the U.S. Marine-Hospital Service and later a parasitologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture, was convinced that hookworm was responsible for many, if not all, of the physical and mental deficiencies ascribed to minority populations in the southern states and was willing to sermonize to anyone who would listen about what he called “the germ of laziness.”3 A golden opportunity came when he presented his ideas to members of the Rockefeller Foundation. Almost immediately, the Rockefeller Commission for the Extermination of [the] Hookworm Disease was created in the autumn of 1909 with a gift of one million dollars from John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937).4

Cooperative agreements were established with eleven states. An army of sanitary inspectors was deployed, each one equipped with a Bausch & Lomb collapsible microscope designed to fit in a saddlebag, a supply of medicine, popular literature for distribution among the curious, photographs and charts to illustrate daytime lectures, and a lantern with slides for evening demonstrations.5

International Health Commission

A more ambitious effort was launched in 1913 with the creation of the International Health Commission to expand the work of the Sanitary Commission to “other countries and other nations.” In the end, the work was extended to fifty-two countries and to twenty-nine islands.6 Members of the Health Commission agreed from the start that philanthropy should not be confused with charities. Philanthropy should be offered to government agencies and not individuals; it should be of limited duration so as to stimulate self-help not dependence; and it should be withheld unless recipients showed promise of continuing to work after aid had ended.

Hookworm dispensaries

The dispensary was at the center of the hookworm campaign, providing education and treatment to targeted audiences. The first dispensary was established in Columbia, Mississippi on December 17, 1911.7 At the end of the five-year effort, the commission conducted 517 dispensary campaigns, microscopically examined 692,765 samples, and treated 382,129 persons infected with hookworm.4

The international effort required cooperative agreements with the governments of the countries involved. The Board provided technical expertise and a portion of the expenditures, while the host countries facilitated the process and contributed in varying amounts. Once the project was assured completion, the Rockefeller team would gradually withdraw and place the responsibilities on local government and sanitary officials. This practice attempted to create goodwill, assure cooperation, reduce any misperceived prominence for the visiting experts, and emphasize the slogan of the International Health Board: “A partner but not a patron.”6

School of Public Health

Visionaries at the Rockefeller Foundation soon realized that a bottleneck in the campaign to eradicate hookworm disease was a lack of trained personnel. In 1914 the need for establishing a school of public health emerged and in 1918 the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health was endowed and opened with William H. Welch (1850-1934) as its director.8 Students were required to take courses in bacteriology, biostatistics, epidemiology, sanitary engineering, and public health administration. For the first time, a thorough training was provided for full-time public health officials in the US. The International Health Board then expanded this initiative to “girdle the globe” with schools and institutes of public health in Prague, London, Toronto, Copenhagen, Budapest, Oslo, Belgrade, Zagreb, Madrid, Cluj, Ankara, Sofia, Rome, Tokyo, Athens, Bucharest, Stockholm, Calcutta, Manila, and Sao Paulo. Over $25 million was spent in this gigantic undertaking and, as a consequence, improvement in public health around the world was attained “beyond reckoning.”8

Uncinariasis

The parasite responsible for anemia and lassitude in lower socioeconomic populations, although probably alluded to in ancient records such as the Ebers papyrus and Hippocratic writings, was not specifically identified until 1838, when Italian pathologist Angelo Dubini found it in the body of a Milanese woman. Dubini published his findings in 1843 and named the parasite Anchylostoma (from the Greek words for “hook” and “mouth”) duodenale (anatomical location where it was found).9,10 Although Dubini did not identify the pathogenic importance of hookworm, investigators in Egypt and Brazil correlated the parasite with chlorosis (an anemia that affected young women and gave them a greenish pallor) and tropical anemia.11 A peculiar habit of eating dirt (pica) among inhabitants of Fort Meade, Maryland was also related to hookworm infestations.11 Further description of the clinical manifestations stated: “The victims of this invading host become increasingly anemic. Strength is dissipated and growth is stunted. The familiar symptoms are emaciation, protruding shoulder blades—’angel wings’—a bloated stomach, and swollen joints. Ulcers form on the legs and are not easily healed, and the skin becomes sallow. In advanced cases, the appetite is perverted and dirt-eating is not uncommon.”12

Uncinariasis (from the Latin uncina or hook), or hookworm disease, is a helminthic parasitosis classified as a soil-transmitted disease and declared by the World Health Organization as one of the Tropical Neglected Diseases (TND) affecting about 900 million persons worldwide.13 Infected individuals deposit hookworm eggs by defecating. Filariform larvae hatched from eggs in warm, moist soil penetrate the skin of barefoot victims, enter the vasculature, and migrate to the lungs where larvae are swallowed into the digestive system and finally reside in the distal jejunum, where they attach to the mucosa with hooks or dental plates and feed on blood. The worms secrete proteases and anticoagulants that keep the blood from clotting. Each worm consumes from 0.03 to 0.15 ml of blood per day as well as an additional amount lost from incidental mucosal bleeding.14 Females lay up to 30,000 eggs daily and these are then passed out in feces. Heavily infected victims may harbor up to a thousand worms and suffer from severe anemia and hypoalbuminemia. Adult worms are about one cm long and characteristically have a bend or hook near the rostral end, which gives rise to its given name. Two species are identified in humans: Anchylostoma duodenale (Old World worm) and the more prevalent Necator americanus (New World worm). Lewis B. Hackett (1884-1962), director of the Rockefeller hookworm campaign in Panama, had on his desk a jar containing over two thousand worms from a seven-year-old boy whose hemoglobin was only ten percent of normal.15

Treatment

Treatment of hookworm infestation consisted of an initial purge with castor oil or Epsom salts, followed by therapeutic oral doses of thymol or oil of chenopodium. A second treatment was given if stool examinations remained positive. Modern and more effective anthelmintics include mebendazole, albendazole, and pyrantel.16

Conclusion

The Rockefeller international campaign against hookworm was eventually abandoned to focus instead on malaria and yellow fever. At the end of the five-year plan, the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission reported that over one million microscopic examinations had been done and almost half a million people were treated for hookworm disease.4 Frederick Taylor Gates (1853-1929), financial advisor to the Rockefeller Foundation, concluded: “On the whole the evidence seems to show that the campaign of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission against [the] hookworm disease is the most effective campaign against a widespread disabling disease which medical science and philanthropy ever combined to conduct.”17

References

- Farley J. To Cast Out Disease. A History of the International Health Division of the Rockefeller Foundation (1913-1951). New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, 3.

- Ettling J. The Germ of Laziness. Rockefeller Philanthropy and Public Health in the New South. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1981, 187.

- Stiles CW. Early history, in part esoteric, of the hookworm (uncinariasis) campaign in our southern United States. J Parasitol 1939; 25: 283-308.

- Rose W. Work of the Rockefeller Sanitary Commission. Rockefeller Foundation (typed manuscript 8 pp.), Aug. 13, 1914, 4 https://rockfound.rockarch.org/digital-library-listing/

- Ettling, 138.

- Fosdick RB. The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1952, 33-34.

- Ettling, 157.

- Fosdick, 42-43.

- Dubini A. Nuovo verme intestinale umano (Anchylostoma duodenale)constituente un sesto genere del nematoidei proprii dell’uomo. Ann. univ. di med. e chir. Milano, 1843, 106: 5-13.

- International Health Board. Bibliography of Hookworm Disease. The Rockefeller Foundation (Publication No. 11), New York City: Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company, 1922, 16.

- Ettling, 24-26.

- Ettling, 31.

- WHO Expert Committee. Prevention and control of intestinal parasitic infections. WHO Technical Report Series No. 749. WHO; Geneva, 1987, 86 pp.

- Crompton DWT. The public health importance of hookworm disease. Parasitology 2000; 121: S39-S50.

- Isthmian Canal Commission. Canal Record vol. 8, No. 10 (Oct. 28), 94-95, 1914.

- Dock G and Bass CC. Hookworm Disease. Etiology, Pathology, Diagnosis, Prognosis, Prophylaxis, and Treatment. St. Louis, C.V. Mosby Company, 1910, 207-236.

- Gates FT. Chapters in My Life. New York: The Free Press, 1977, 224-225.

ENRIQUE CHAVES-CARBALLO, MD, is a pediatric neurologist and clinical professor, Department of History and Philosophy of Medicine, Kansas University Medical Center, Kansas City, KS.

Spring 2021 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply