Stephen Martin

Durham, England, and Thailand

The recent film The Dig1 has brought into the wider public eye the story of an Anglo-Saxon ship burial.2 The burial mound, at Sutton Hoo, in Sussex, England,3,4 contained a high-status figure, almost certainly Royal. The most expensive of the grave goods5 are high-craftsmanship gold, set with very finely-cut garnets and some minuscule blue glass fragments in inspired designs. They are breathtaking masterpieces. Similar examples from the time are to be seen from Street House, Loftus, England,6 the Staffordshire hoard,7 and the pectoral cross of Saint Cuthbert in Durham.8 It is an interesting question as to how many English workshops produced this kind of jewelry and where. We simply do not know, but they cluster in Anglo-Saxon England.

|

|

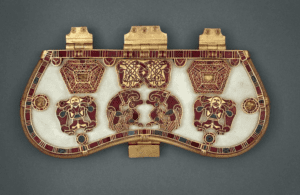

Fig 1. The Sutton Hoo purse lid. Gold, glass, and garnets, early seventh century. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 © The Trustees of the British Museum. |

The likely candidate for funding and occupying the ship burial is King Redwald, who ruled over East Anglia in the first quarter of the seventh century. The Venerable Bede described9 that Redwald killed the Christian King Edwin of Northumbria in battle, when Redwald’s son, Raegenhere, was also killed.10 Edwin had earlier been banished to Redwald’s court.11 Bede was appalled that, despite converting to Christianity in Kent, Redwald was “seduced” by his wife and “perverse teachers” into the depraved worship of Christ and demons, both at the same time, at separate altars in the same temple.12 Bede also described Redwald, “the same pagan King,” as later killing the Christian King Oswald of Northumbria in an intense battle.13 A candidate site for Redwald’s headquarters has been found at the Anglo-Saxon settlement outside nearby Rendlesham village, with a hall, metalworking, and some fine gold objects.

The purse lid (Fig 1) has seven images in two rows, with left-right symmetry. Other components riveted to the purse in wood, leather, or cloth had decayed. The lid’s upper row has corner decorations of two intricate, filigree-pattern, irregular hexagons. Between these is a panel with two trees of life, each having a central leaf. As a symbol further strengthening the trees’ power, each of these emblems of survival is supported by a pair of muscular boars with rough-haired backs. The central two are intertwined. The tree of life was a prominent Germanic religious theme, linked to the venerated tree Irminsul. Charlemagne destroyed it to bring in Christianity. Tree of life motifs lasted well into Christian times on Anglo-Saxon and Viking crosses, and still appealed to William Morris in Arts and Crafts design. Its choice on the purse must have been a protective amulet. Redwald’s risk of death and wounding was high as a battle commander. The apparent psychology of a sense of protection was surely no coincidence.

The bottom row has a curious repetition of a motif. In the knowledge of the images’ likely meaning, there is an explanation for this. There are outer scenes of a mustached man, with two arms and two hands,14 his knees bent as if seated to eat, with two wolf-like figures apparently licking an ear each in gratitude. The Nordic-Germanic god Odin had two wolf companions—Geri and Fleki, meaning Greedy and Glutton. Odin did not eat, but was self-reliant enough to give all of his food every night to the wolves.15 That story symbolizes the ability to survive death from famine, a real risk in living memory in those times.

|

| Fig 2. Bracteate amulet brooch, from Funen, Denmark, c. AD 500. The raven is facing Odin in eye-to-eye conference. An early ward round? The foal holds up its injured left fore-leg. It is not Odin’s horse, Sleipnir, which had eight legs. National Museum of Denmark, Copenhagen. CC BY-SA 3.0. In online cat. as asset 19455. |

Next, are a pair of typically-stylized, Saxon-Viking curved-beak ravens, both eating ducks, starting with the heads.16 Odin had two ravens, Huggin and Munnin, who flew around the world during the day and reported back to him on the day’s dead and wounded.17 They had to eat. Their reports linked to Odin’s role in resurrection. A single raven also occurs on numerous protective amulet brooches from Denmark and Sweden, with Odin healing a wounded foal. The runes of the one illustrated (Fig 2) refer to Odin as the high one and probably contain the word alu, ᚨᛚᚢ, meaning heal, protection, or amulet. Importantly, this precedes the date of the purse, proving that the Odin amulet and healing concepts were already established. Furthermore, ale and heal appear to be in the same word field, implying that early beer was seen as medicinal. The purse’s ravens are also a potential medical invocation, helping Odin with any healing.18

With Odin seated again with his grateful wolves, lower right, the scenes have come full circle across twenty-four hours, from one evening meal to the next. That seems to refer to surviving a day and warding-off death, disease, injury, and famine. It is a purse, so having the coinage resources to do all that links to the object, as well as its amulet status.19

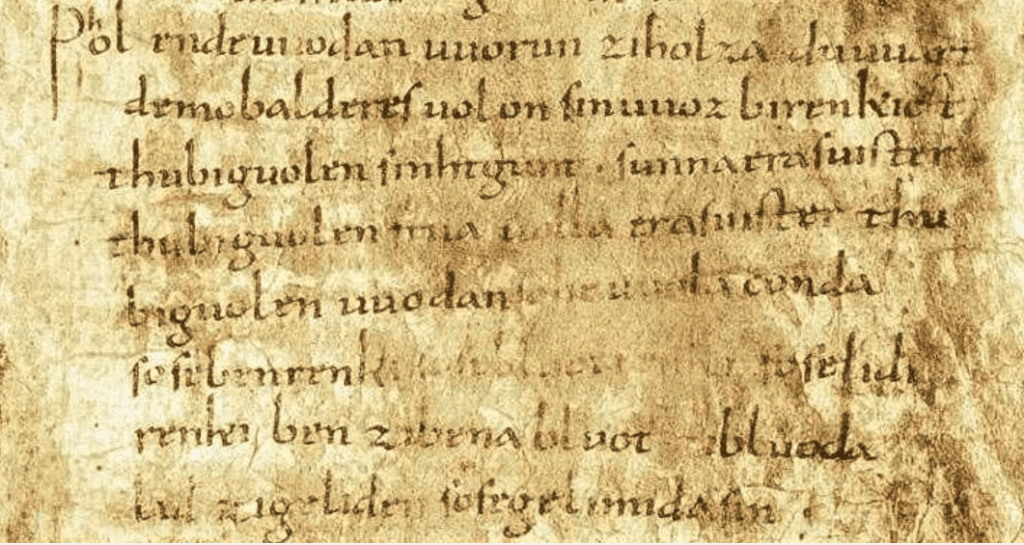

An additional clue to the purse images as an amulet lies in a surviving description of Odin healing the foal, transcribed in the early AD 900s.20 The manuscript came from Fulda, Hesse, and was noted by Jacob Grimm in his folk tale research. It is an addition to a book leaf, now in Merseburg Cathedral library. (Fig 3) Odin is mentioned in Germanic form as uuodan on line 5. The incantation is the last three lines. Odin and two women, Sinthgunt (line 3) and Frija (line 4), conjure a spell, categorizing the leg’s anatomical damage:21

So se ben renki so se bluot renki so se lidi

renki ben zi bena bluot zi bluoda

lid zi geliden so se gelimida sin.

So the bone wrenched, so the blood wrenched, so the tendon

wrenched. Bone to bone, blood to blood,

tendon to tendon, so let it all be rebound.

Renki is very similar to wrenched. The idea of blood wrenched might relate to damaged blood vessels viewed in the same system as blood. The word leader is used for tendons in some northeast English and northwest German dialects, like lidi. Gelimida is in the same linguistic word field as boundary, hence the translation rebound.

Besides battle, what were the frightening threats to life in Anglo-Saxon times that needed hope, comfort, and the relief of anxiety? Between 5,000 and 30,000 people migrated from northwest Germany. Factors may have included the Justinian plague in AD 542 from Constantinople, or famine in AD 535-536, when a likely volcanic eruption caused worldwide cooling, darkness, and crop failures.

|

| Fig 3. The story of the injured foal and the healing incantation. Merseburg Cathedral Library, Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. Codex 136, f. 85r. Public domain. |

In neuropsychiatry, there is important literature on how mood chemistry, mood itself, time of day, and the cortisol hormone system interact. The Anglo-Saxons used a word uhtceare, meaning sorrow at dawn,22 a surprising insight into the diurnal variation of endogenous depression, now known to be related to stress hormone damage and subsequent cortisol hormone dysfunction. This affects mood and activity cyclically. Low adrenal gland function and compensatory gland enlargement are common in chronic depression. The Saxons’ wide range of terms for depression indicated great psychological mindedness, consistent with a sense of healthy mental diurnality, in the frieze of the purse lid.

The purse motifs should not be underestimated as simple design or mythological stories. Interpreting images and emblems of Odin, chief of the early Anglo-Saxon gods, makes them more powerful in their original meaning, with greater psychological impact, importance in protection, and warding off evil: apotropaism. We readily disconnect from spirituality in early religion, but on the basis of human need, human function, and human stresses, faith and mysticism must always have been operant. Exploring the Rhineland for Roman remains in churches, I was surprised and moved to see a candle burning on a Viergötterstein of four Roman gods inside a beautiful, ancient Christian church tower.23 This stone originally topped a column in the village. I was not horrified at paganism, but touched by a tolerant homage to previous faiths. It seemed to bow to those who, 2000 years ago, had no idea of present religions, yet still drew respect for their long-forgotten religious faith, which must have been just as valuable to them as it is to us now. There is an argument for past, as well as present religious tolerance to help us to open our eyes and learn more.24

The Dig has a poke at the academic establishment for scoffing at semi-professionalism. There may have been an element of that in the real-life excavation. It still goes on. Nowadays there are, thankfully, more organizations that are true open institutions, fostering new thinking from scholars at all levels. Long may they thrive.

The French historian Marc Bloch wrote that there should be more work reading art for historical meaning,25 without documents. This is important, as so much visual material has no record. It is also tricky, because it needs knowledge across disciplines and time to consider the factors. It also needs caution. However, if you put the hours in, it can, on occasion, open doors to wonderful revelations. There comes a point where so many factors slot together, that you know with a warm gut feeling when other explanations are highly unlikely. There is also a point of proof in statistical probability, when you multiply the pool of factors. Bloch’s method is therefore an art and a science.26

What is striking in the Sutton Hoo purse lid is that the owner was a wealthy connoisseur, keenly interested in contemporaneous, selected religious emblems. He had a sense of the interplay between survival, health, wealth, contentment, and the daily round. He did not want to be killed or injured. The function of the purse as an Odin amulet is a new concept, linking to fascinating evidence for Odin as a healer. This purse analysis is a good fit for Redwald, given Bede’s account, and a substantiation—though not absolute proof—of him as the occupant of the ship. Either way, Redwald must have been rich from conquest, and clinging extravagantly to paganism against the tide of Christianity.

End notes

- The Dig, directed by Simon Stone, Magnolia Mae Films, Clerkenwell Films, distributed by Netflix, 2021.

- Brown, B. Basil Brown’s diary of the excavations at Sutton Hoo, in 1938-1939, chap. 4, in Bruce-Mitford RLS. Aspects of Anglo-Saxon Archaeology: Sutton Hoo and other discoveries. Harper & Row Publishers, New York, 1974. Most British burial mounds are from the Bronze Age, but those at Sutton Hoo are late examples. They are anachronistic by a millennium, because they persisted in Germany throughout Romano-Germanic centuries.

- Phillips C W. The Excavation of the Sutton Hoo Ship-burial. The Antiquaries Journal, Society of Antiquaries of London. XX (2), 1940, pp. 149–202.

- Bruce-Mitford, RLS. The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial. Vols. 1-3, British Museum, London, 1975, 1978, 1983.

- Williams G. Treasures from Sutton Hoo. British Museum Press, London, 2011.

- Sherlock S J. A Royal Anglo-Saxon Cemetery at Street House, Loftus, North-East Yorkshire. Tees Archaeology Monograph Series, Vol 6, 2012. The finds are in Kirkleatham Museum. The inclusion in one of a Whitby jet centerpiece implies local manufacture, but possibly by an itinerant goldsmith.

- Fern C, Dickinson T, Webster L, Eds. The Staffordshire Hoard: An Anglo-Saxon Treasure. Research Report of the Society of Antiquaries of London, 2019.

- http://collections.durhamcathedral.co.uk/Details/collect/3230 Accessed March 2021.

- Bede. Historical Works. Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation. Ed. & trans. King JE, after Stapleton, T. Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London England, 1933, reprinted 1999. Book II, Chapter V, pp. 224-5. He wrote ‘Reduald rex Orientalium Anglorum.’

- Bede, op. cit., Book II, Chapter XII, pp. 278-9. Raegenhere is possibly another candidate for the ship burial.

- Bede, op. cit., Book II, Chapter XII, pp. 270-1.

- Bede, op. cit, Book II, Chapter XV, pp. 292-3. He wrote ‘Reduald iamdudum in Cantia sacramentis Christianae fidei imbubtus est, sed frustra: nam rediens domum, ab uxore sua et quibusdam perversis doctoribus seductus est, atque a sinceritate fidei depravatus habuit posteriora peiora prioribus; … Atque in eodem fano et altare haberet ad sacrificium Christi, et arulam ad victimas daemoniorum.’

- Bede, op. cit, Book III, pp. 368-9. He wrote ‘… occisus est comisso gravi praelio, ab eadem pagana gente paganoque rege Merciorum, a quo et praedecessor eius Aeduini peremptus fuerat, …’

- The god Týr/Tiw had a hand eaten by a single wolf, so this gravitates against him on the purse. See version in Dodds J. The Poetic Edda. Coach House Books, Ontario, 2014.

- Faulkes A. Trans. Edda. Everyman, London, 1995. The exact date and origin of the themes in this Icelandic poem are not known, but it is reasonable to assume Germanic roots from Germanic theology.

- Bede repeatedly showed an urgent sense of a gentle Christianity displacing the death, violence, and aggression of Germanic polytheism, which was intrinsically linked to warfare. Large corvids typically stun and kill with beak blows to the cranium, a level of symbolic violence that looks carefully selected here. Raptors kill with talon trampling. Corvids commonly have beak supercurvature, a point of potential marvel for early observers. It may be viral in origin: https://www.usgs.gov/centers/asc/science/possible-causes-beak-deformities?qt-science_center_objects=0#qt-science_center_objects Accessed March 2021.

- Faulkes, A. Edda. Op. cit.

- The Sutton Hoo shield also had a single raven appliqué, as if to say the raven of doom has already been here. It looks like a heraldic prototype, starting as an apotropaic device. Illustrated in: Williams, Treasures, op. cit. Redwald was obviously no stranger to death in ‘grave battle’ and bereavement with the death of his son. He also knew what he did to Edwin and Oswald could be done to him.

- Amulets are still ubiquitous in south and southeast Asia – a sense of their Anglo-Saxon use helps to illustrate their origins in times of greater threat to life.

- Fuller SD. Pagan Charms in Tenth-Century Saxony? The Function of the Merseburg Charms. Monatshefte, Vol. 72, No. 2, Summer 1980, pp. 162-170. Fuller argues persuasively for the date of the text, taken from previous oral tradition.

- Author’s translation. As a medical student in the Rhineland, I took histories from many patients who only spoke dialect and no high German or English. Like Newcastle Geordie, it was an unplanned insight into the basis of a lot of Anglo-Saxon words.

- Anon. The Wife’s Lament. The Exeter Book. Folio 115, Exeter Cathedral Library, UK. The book is probably late tenth century. The date of the original writing is unknown.

- This is at Hottenbach, in the Hunsrück. They are Juno, Minerva, Mercury, and Hercules. Several Christian churches in the Rhineland Palatinate are built on top of Roman villas and temples, an obvious cultural continuity in using both ideational and structural foundations.

- The University of Trier, in a city with strong Roman Catholic links since it was Constantine’s Christian imperial capital in the fourth century AD, commendably encourages doctoral study in comparative religion.

- Bloch M. Apologie pour l’histoire ou métier d’historien. Libraire Armand Colin, Paris, 1941. Published in several English editions as The Historian’s Craft.

- Bloch was murdered for his religion in World War II, otherwise he could have lived to exercise greater influence over history in images.

STEPHEN MARTIN is Honorary Professor of Psychiatry at Chiang Mai University, a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, and a Member of the British Neuropsychiatry Association. He holds approbation to practice medicine in the Rhineland Palatinate, Germany. He won the Newcastle upon Tyne University George Henderson Scholarship for Medical History, supervised by Professor Norman McCord. Before part-retiring, he also held professorships in psychiatry in the UK and in the arts studying cultural history. As a boy, he grew up in the trenches of his father’s archaeological digs in Yorkshire.

Winter 2021 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply