Peter Arnold

Sydney, Australia

|

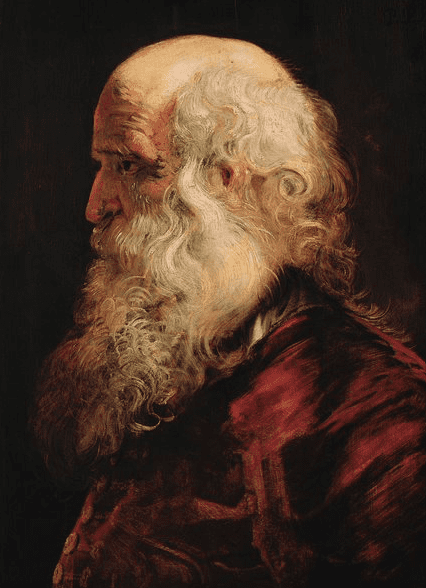

| Study of the head of an old man. Peter Paul Rubens. between 1610 and 1615. Kunsthistorisches Museum. Via Wikimedia. |

A noticeable phenomenon of the twenty-first century is the increasing frequency of friendships between older men. The importance of such friendships to both mental and physical health has been well documented.1,2,3 This issue has particular relevance to older male doctors, especially in the UK, where doctors tend to retire early.4

Many doctors establish close friendships during the long university years, junior hospital years, and specialty training. Many of these “comrades,” if they are lucky, survive into retirement and old age. Some might have left their homelands and emigrated to other countries as a result of scholarships, advanced research facilities, or better-paid jobs. They leave most of their early friendships behind, but in retirement, they have time to reflect. Where are those colleagues who once were close friends, and what have they done with their lives?

In the past, contact often fell away because of busyness and the delays of international communication. Today, the internet makes it possible to try to re-establish contact with old friends, even though COVID-19 has ruined any current possibility of meeting in person. What happened to their ideals and ambitions? Have they achieved their initial goals, or did some event change their direction and determine the course of their careers? Who or what played a part in their decisions? Are they single, married, divorced, or widowed? Have they lost spouses, children, or grandchildren—or yearned for children they never had?

Through decades of practicing medicine, patients are often doctors’ most enduring social contacts. Perhaps they were acquainted with other professionals, such as accountants, lawyers, or dentists—exceptionally, patients. Hospital-based work and professional organizations might also have provided opportunities to cement new friendships. But over the decades, one hears or reads of the deaths of colleagues who once were vibrantly alive and excelling in their careers. And many bright minds and erudite intellectuals have disappeared inside impenetrable shells of dementia.

Today, many nonagenarian doctors are widowers, stranded and companionless. Their children are often at the peaks of their own careers, and grandchildren are likewise establishing themselves in work and relationships. Solitude becomes the norm, whether at home or in an aged care facility, where there are few options to discuss issues of the day.

Depression often seizes this opportunity.

If an older doctor is fortunate, a younger retired colleague—who might once have referred patients to them—picks up the mantle of companionship, sharing an occasional meal at a favorite restaurant or café.

Is there a lesson to be learned? Why not think empathically about older retired colleagues and make a point of spending some time with them?

After all, we are all on different points of the same trajectory.

References

- Peter O. Peretti and Linda Tero, PSYCHOLOGY AND HUMAN DEVELOPMENT, (ISSN: 2537-950X), 1984, 1(1), 25–31

- John W. Osborne Psychological Effects of the Transition to Retirement. Canadian Journal of Counsellingand Psychotherapy, Vol. 46 No. 1 © 2012 Pages 45–58

- Toni M. Calasanti. Gender and Life Satisfaction in Retirement: An assessment of the Male Model. Journal of Gerontology: SOCIAL SCIENCE 1996, Vol. 51B,No. I.S18-S29

- Smith F, Goldacre MJ, Lambert TW. (2018) Retirement ages of senior UK doctors: national surveys of the medical graduates of 1974 and 1977. BMJ Open; 8:e022475. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022475

PETER ARNOLD is a retired family doctor and professional editor in Sydney. Former Chairman, Australian Medical Association.

Winter 2021 | Sections | Doctors, Patients, & Diseases

Leave a Reply