Tonse N. K. Raju

Gaithersburg, MD, United States

|

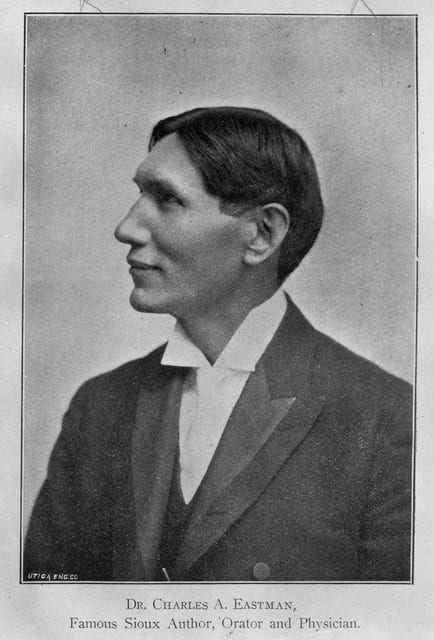

| Figure 1. Dr. Charles Alexander Eastman; Reproduced with permission, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN |

On March 15, 2021, the United States Senate confirmed Rep. Deb Haaland (D-NM), a member of the Laguna Pueblo Tribal Nation, as Secretary of the Department of Interior. This historic action marks the beginning of an end to centuries of invisibility of Native Americans in high-profile government positions. Even previously famous Native Americans have faded into collective amnesia.1

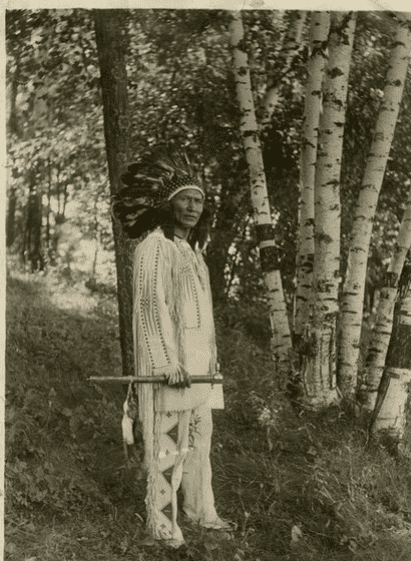

Consider Dr. Charles Alexander Eastman (1858–1939), a pioneer Native American doctor, known as “Ohiyesa” to his family and to the members of the Santee Sioux Native American tribe (Figure 1 and 2). He graduated from an Ivy League college in the nineteenth century and obtained an MD from a US medical college.2 A reformer, pioneer, and an author of nearly a dozen books,3-12 Eastman was the topic of a biography,2 a documentary,13 and the focus of the 2007 HBO film Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee based in part on a 1970 nonfiction book.14-15 One of the most famous Native Americans during his time, Eastman is hardly remembered by the medical community today.

Ohiyesa’s maternal grandmother, a Medwankton Sioux, married well-known artist Captain Seth Eastman. Their daughter, Mary Nancy Eastman, married Chief Many Lightnings, a Wahpeton Sioux in 1847. Charles was their fifth child. Sadly, his mother died following his birth. At age four, he was given the Native Indian name “Ohiyesa” (the Winner). During the Sioux Uprising of 1862, he got separated from his father and fled from Minnesota to Canada with his grandmother and his father’s brother Mysterious Medicine (whose other names were White Foot Print, Big Hunter, and Long Rifle).14 As Ohiyesa grew up, he learned the ways of Native American culture and heritage. When he was fifteen, he reunited with his father, returning to their home in today’s South Dakota.

Ohiyesa, renamed Charles Eastman,2 earned a BS from Dartmouth College in 1887 and an MD in 1890 from the Boston University School of Medicine. He was the third Native American to earn a medical degree in the United States—after Dr. Susan LaFlesche Picotte of Omaha, who was the first, and Dr. Carlos Montezuma from Chicago, who was the second; both received their MDs in 1889. Eastman took up employment in the Office of Indian Affairs later that year and was assigned to work as a physician at the Pine Ridge Agency in South Dakota.

Then, there was the Wounded Knee Massacre on December 29, 1890. Although he was not an eyewitness to the massacre, he arrived at that site on New Year’s Day 1891 despite a blizzard and the US Army’s efforts to delay him. To his horror and sorrow, he saw the scattered remains of the dead and wounded who were (as he wrote later) “. . . relentlessly hunted down and slaughtered while fleeing for their lives.” He added, “. . . When we reached the spot where the Indian camp had stood, among the fragments of burned tents and other belongings, we saw frozen bodies lying close together or piled one upon another. It took all my nerve to keep my composure in the face of this spectacle, and of the grief of my Indian companions, nearly every one of whom was crying aloud . . .” He was the only doctor available and did his best to treat the wounded and helped to bury the dead.

|

| Figure 2. Portrait of Dr. Charles A. Eastman (Ohiyesa), at the estate of Mr. Ward Burton, Lake Minnetonka. Reproduced with permission, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, MN |

Eastman continued working as a reservation physician until 1903. He was the president of the Society of American Indians following World War I. During the 1920s, he served as an inspector of the conditions of Native American reservations. He died on January 8, 1939.

Eastman has been hailed for his remarkable ascent within the ranks of white society’s social and administrative domains and for extraordinary contributions to educate and preserve Native American identity. He accomplished these through a set of brilliant writings (assisted by his wife Elaine Goodale Eastman), lectures, and government work. He also cultivated relationships with legislative branch members and served on key committees, such as the Committee of One Hundred Advisory Council, which recommended reforms on federal Indian policies.14 He encouraged outdoor education and worked as Indian secretary for the YMCA. Later he helped found the Boy Scouts of America. Between government posts, he continued to practice medicine while being active with his lobbying efforts. The cumulative effect of such efforts increased acceptance of Indian culture and rights in the general population.

Dr. Eastman was a pioneer, social activist, and a man with a vision and a noble soul. He tried to educate society about the contributions of Native Americans to American culture and civilization. Yet, he is hardly remembered these days.

This can be rectified, as the selection of Ms. Deb Haaland as the Secretary of Interior has attempted to rectify past wrongs. In her role, she will supervise the operations of one-fifth of the United States land mass which once belonged to Native Americans.

To honor Dr. Eastman, professional medical societies can create awards or scholarships in his name, and his biography could be included in the curriculum of medical colleges, encouraging generations of Americans to learn the legacy and contributions of Native Americans to all Americans.

Acknowledgment: I wish to thank Dr. Gail Johnson, Ms. Diane D. Evans, and Dr. Jeffery Evans for their help with making sure the accuracy of the contents of this paper.

References

- Reclaiming Native Truth, A Project to Dispel America’s Myths and Misconceptions. https://rnt.firstnations.org/. Published 2016-2018. Accessed January 24, 2021.

- Wilson, R. Ohiyesa: Charles Eastman, Santee Sioux. Urbana, University of Illinois Press 1983.

- Eastman, CA. Memories of an Indian Boyhood, autobiography; McClure, Philips, 1902.

- Eastman CA. Indian Boyhood, New York; McClure, Phillips & Co., 1902.

- Eastman CA. Red Hunters and Animal People, legends; Harper and Brothers, 1904.

- Eastman CA. The Madness of Bald Eagle, legend; 1905.

- Eastman CA. Old Indian Days, legends; McClure, 1907.

- Eastman CA, Goodale-Eastman, E. Wigwam Evenings: Sioux Folk Tales Retold, legends; Little, Brown, 1909.

- Eastman CA, Goodale-Eastman, E. Smoky Day’s Wigwam Evenings, 1910.

- Eastman, CA. The Soul of the Indian: An Interpretation, Houghton, 1911.

- Eastman CA. Indian Child Life, nonfiction, Little, Brown, 1913.

- Eastman CA. Indian Heroes and Great Chieftains, Little, Brown, 1918.

- Beane, K. The Vision Maker Media documentary OHIYESA The Soul of an Indian (2018).

- HBO film Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee (2007).

- Brown, D. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, 1971 New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1970.

TONSE N. K. RAJU, MD (Pediatrics), DCH, FAAP, completed a pediatric residency at Cook County Hospital and a Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine fellowship at the University of Illinois in Chicago, where he served as Professor of Pediatrics. He is currently an Adjunct Professor of Pediatrics at the Uniformed Services University in Bethesda, and the Deputy Editor for the Journal of Perinatology. He is the author of two medical history books, one of which is titled The Importance of Having a Brain: Tales from the History of Medicine.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Winter 2021 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply