JMS Pearce

East Yorks, England

|

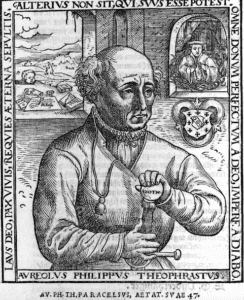

| Fig 1. Aureolus Philippus Theophrastus von Hohenheim (Paracelsus). Via Wikimedia. |

Alterius non sit qui suus esse potest

Let no man be another’s who can be himself

Paracelsus 1552

Paracelsus was the most original, controversial character of the Renaissance,1 who brazenly questioned and condemned the dictates of Galen and other ancient physicians. In an age of mysticism and alchemy, this solitary figure laid the foundations of medicinal chemistry and rational science by means of observation, experiment, and deduction.

Born in Einsiedeln in Switzerland, Philippus Aureolus Theophrastus Bombastus von Hohenheim, known as Paracelsus (1493-1541) (Fig 1), was the only son of an impoverished German doctor and chemist. In childhood, his father taught him the rudiments of alchemy, surgery, and medicine. His mother died when he was young, and his father moved to Villach in Austria. There, Theophrastus trained at Fugger’s mining school, learning about metallic ores and the Philosopher’s Stone;a he also studied at the Benedictine monastery at Lavanttal.

He learned about metallic ores in smelting vats, and the notion of changing lead into gold—the claim of alchemists of the time. In 1507, he impressed the humanist Vadianus, who encouraged him to study medicine. His experiences in metallurgy and chemistry founded his later original ideas, from which evolved an early pharmacotherapy, which he held in alliance with his more abstruse ideas of mystic stellar influences and religion. In later years he believed that metals were the key elements of the universe, controlled by God the “great magician,” who created nature. But he discarded the alchemists’ notion of changing base metals into gold.

His teacher Johann Trithemius, a practitioner of magic, alchemy, and astrology, and abbot of St. Jacob at Wurzburg (1461-1516), was a major influence. From 1507 Paracelsus traveled all over Europe and the Middle East, attending the Universities of Basel, Tübingen, Vienna, Wittenberg, Leipzig, Heidelberg, and Cologne. He continually sought knowledge of alchemy and science to uncover “the latent forces of Nature” and their use.

He who is born in imagination discovers the latent forces of Nature . . .

Befriended by its rector Vadianus, he graduated from the University of Vienna in medicine in 1510/11. He probably received a doctorate degree from the University of Ferrara in 1516. No journeyman, he then began immodestly to use the name “Paracelsus”—comparing himself to Aulus Cornelius Celsus, the revered first-century Roman medical encyclopedist.

With his critical mind he was appalled by, and frequently upbraided, many practices he encountered. He became an outspoken, heretical, anti-authoritarian freethinker. He asked how “the high colleges managed to produce so many high asses,” a typical Paracelsian taunt. He said: “A doctor must be a traveller . . . Knowledge is experience . . .”; “the crude language of the innkeeper, the barber, and the teamster had more real dignity and common sense than the dry scholasticism of Aristotle, Galen and Avicenna”—all cherished authorities in his time. He disparaged universities’ teachings, so a doctor must seek out old wives, gypsies, sorcerers, wandering tribes, old robbers, and such outlaws and take lessons from them.

|

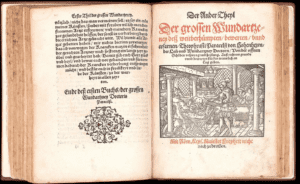

| Fig 2. Der Großen Wundartzney 1863 3rd edn. from: Museum Für Medizinhistorische Bücher Muri. Marktstrasse 4 CH-5630 Muri. |

Between 1524 and 1527, he settled in Salzburg, practicing medicine. He exercised his art as both physician and teacher of alchemy, believing medicine and alchemy should be integrated. He treated all who came to him regardless of their wealth or political creed; he included gravely ill patients rejected as hopeless by other doctors. He allegedly had success in patients suffering leprosy, cholera, and cancer, often without charging a fee. He fled Salzburg, having been accused of treating peasants in their revolt against the authorities. Meanwhile his miraculous cures had made him famous.

In 1527 he successfully treated a leg infection of Johann Froben, a prominent publisher and friend of Erasmus (1466-1536). On their recommendation and with support from his friend Wolfgang Capito and patron Oecolampadius, in June 1527 he was appointed a Town Physician of Basel. The appointment subsumed Professor in Physic, Medicine, and Surgery at the university. But troubles were imminent.

A rebellious outsider, his unorthodox methods, his teaching in German rather than conventional Latin, and his haughty superiority provoked widespread jealousy and disdain. But he was popular amongst visiting students from Europe. His lectures stressed the healing power of nature and scorned many orthodox methods.2 He advertised his lectures on June 5, 1527, inviting not only students but also the public. The university authorities were less than happy. Three weeks later, in front of them, Paracelsus burned the writings of Galen and Avicenna; he explained: “Reading never makes a physician. Medicine is an art and requires practical experience.” The town’s authorities recalled the heinous act of Luther, who in 1520 at Wittenberg had burned a papal bull that threatened excommunication. Paracelsus refuted this comparison.

He derided the use of many pills, salves, infusions, electuaries, fumigants, and drenches. Not surprisingly, by 1528 he had fallen into disrepute with local doctors, apothecaries, and magistrates, and without support from Froben—now dead—he was exiled from Basel.

|

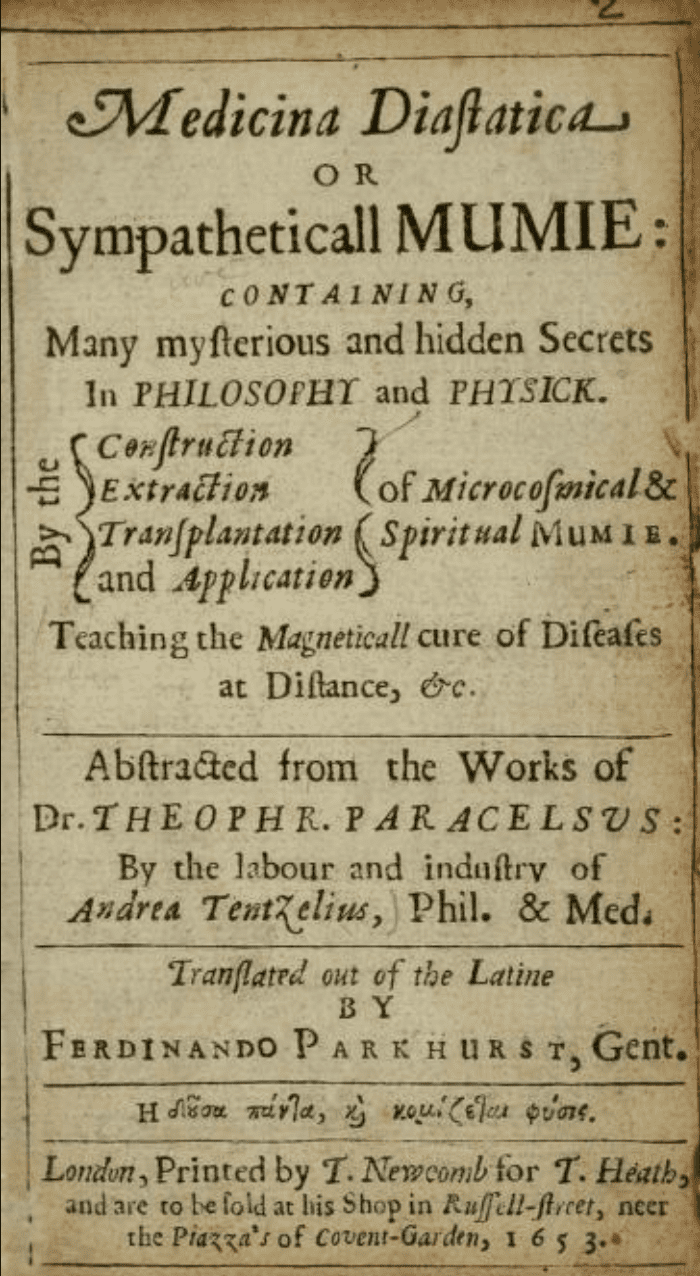

| Fig 3. Paracelsus. Medicina Diastatica Containing Many Mysterious And Hidden Secrets In Philosophy And Physic. 1653. Via the Internet Archive. |

Ever restless, ever hungry for knowledge, he traveled to the Upper Alsace, dressed like a vagabond, impecunious and reviled for his work. Leipzig’s medical faculty forbade printing of his books. He again moved on to Regensberg, Switzerland to visit his old friend and mentor, Vadianus. He was given full citizenship and the freedom to practice his art and publish his writings. From Regensberg he wandered the Canton for three years; his practice and writing now veered towards speculation and meditation of spiritual matters.

In 1536, based on his wartime surgery, he compiled his Der grossen Wundartzney—Great Surgery Book (Fig 2), which helped to resurrect his reputation and practice. But most of his copious articles emerged after his death, compiled by Johannes Huser and published by the Waldkirch Publishing House in ten volumes at Basel in 1589-1591.3 (Fig 3)

In May 1538, he returned to Villach to see his father, only to find that he had died four years earlier. In 1541 after making a comprehensive will, Paracelsus died at the White Horse Inn, Salzburg, though the cause was subject to many dramatic, speculative suggestions. He was forty-seven years old. In spite of his seditious behavior, a strong if controversial Paracelsian movement and later iatrochemists arose in the century after his death.4

Contributions to medicine

To understand the complexities of Paracelsus we have to remember his prime purpose was to translate alchemy into the most effective chemical treatments of disease and to discover how to employ the latent forces of nature. His applied chemistry superseded ancient theories of earth, air, fire, and water.

Paracelsus believed that man was the epitome of a divine heaven that exists outside of man but is ingrained within him. His universe as a macrocosm connects with the human being as a microcosm.1 It was the physician’s job to unravel these natural phenomena to show how the organs work in health and disease. The distribution of the different salts in the outside world constituted an anatomy of its own: the Anatomia Elementata.5

Paracelsus investigated many diseases, and conjoined alchemy and secret remedies (Fig 3) with chemical medicines.1 Having experience as a military surgeon with both Dutch and Venetian armies, he opposed the separation of medicine from surgery: “there can be no surgeon who is not also a physician.”

He initiated the use of iron, sulfur, mercury, arsenic, and antimony, thus applying chemistry to medicine, as acknowledged by the first London Pharmacopoeia, 1618. And he developed an alcoholic tincture of opium that he called laudanum;b he had acquired opium in Constantinople and was rumored to have hidden it in the handle of his sword. The pain and anxieties of his patients (and millions thereafter) responded to his prescription of laudanum.

He denounced the treatment of wounds by padding with moss or dried dung.

The wounds must drain, for “if you prevent infection, Nature will heal the wound by herself.”

He also recognized psychological symptoms; Carl Jung later wrote “we see in Paracelsus not only a pioneer in the domains of chemical medicine, but also in those of an empirical psychological healing science.”6

“Miners’ disease” (silicosis) he attributed to the inhalation of metal vapors and not, as generally believed, a punishment for sin administered by spirits.

Long before Sydenham described rheumatic chorea in 1686, Paracelsus recognized “chorea naturalis,” an emotional instability and loss of voluntary motor control in Saint Vitus’ dance.

He recorded the symptoms and signs of dropsy and observed that in the late stages the urine “decreases and thickens.” By adding wine or vinegar to urine he noted it curdled because of precipitation of albuminous protein.7

In De generatione stultorum he reported in Strasbourg the correlation between cretinism and endemic goiter, suspecting a cause in drinking water long before the identification of iodine deficiency.

In 1530 Paracelsus wrote a clinical description of syphilis, described congenital transmission, and its treatment with mercurials.

Though mostly sound in his opinions, at times he inclined to the bogus practice of homeopathy, advocating “small doses of what makes a man ill also cures him.” He was alleged to have cured many victims of plague in Stertzing in 1534 by administering a pill made of bread containing a minute amount of the patient’s excreta he had removed on a needlepoint.

Legacy

Paracelsus remains a mysterious personality but was undoubtedly one of the founders of modern scientific medicine.8 He was a Laputan, a free and independent spirit, but a deeply religious idealist and original thinker who was acknowledged as an exceptional physician in his time. He related knowledge to cosmic influences and failed to understand how a cadaver could shed light on disease; thus his contempt for anatomy.

With his egregiously abrasive opinions, he provoked jealousy and many victims of his scorn understandably disliked him. However, Paracelsus insisted that doctors based their medicine on four pillars: Philosophia, the custom of natural substances; Astronomia, connects the universe as a macrocosm with the human being as a microcosm; Alchemy, an art of extracting the effective healing principle from natural substances; and virtus, the virtue that assures the doctor of God’s love.

He built the foundation for the advances of the seventeenth-century Enlightenment, exemplified by William Harvey, Descartes, and Newton.

Several literary figures recognized his learning and influence. In Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well, Act 2, Scene 3 we read:

PAROLLES: So I say, both of Galen and Paracelsus.

LAFEW: Of all the learned and authentic fellows—

And the Victorian romantic poet Robert Browning extolled him in a five-part saga Paracelsus in 1835, (Fig 4) in which a lengthy dialogue shows his ambition to attain ultimate truths through intellectual accomplishment, as well as showing his character flaws.

Perhaps we can see him as a man so relentlessly driven by pursuit of knowledge to benefit the health of the common man that he was undaunted by the hostility he provoked in his contemporaries.

Stamps issued in Hungary, Austria, and Germany commemorate him. (Fig 5)

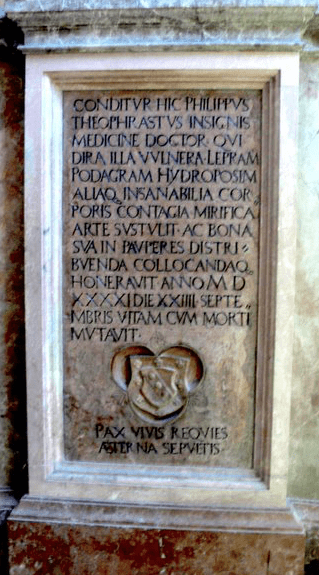

His gravestone in Salzburg recounts (Fig 6):

“Here lies Philippus Theophrastus, Doctor of Medicine of great renown, whose art most wonderfully healed even wounds, leprosy, podagra, dropsy, and other incurable diseases; and who is honored by having his possessions distributed to the poor. He passed from life to death on September 24 of the year 1541.”

|

|

|

| Fig 4. Paracelsus by Browning. 1835. Image via John Windle Antiquarian Bookseller | Fig 5. Paracelsus stamp | Fig 6. Paracelsus’ Gravestone, St Sebastian, Salzburg |

End Notes

- The Philosopher’s Stone was a legendary alchemical substance with magical properties. It was used to create the Elixir of Life, which made the drinker immortal, as well as transforming any metal into gold. Its re-discovery and destruction are told in JK Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone.

- Paracelsus’s laudanum in addition to opium contained powdered gold, amber, and pearls. But he frequently used opium as liquors, sucus, and opium papavere. Thomas Sydenham developed a purer alcoholic tincture of laudanum in 1676.

References

- Pagel W. Pagel W. Paracelsus. An Introduction To Philosophical Medicine In The Renaissance. Basel 1958. 2nd edn. Karger 1982

- Grell OP. ed, Paracelsus The Man and his reputation, his ideas and their transformation. Leiden, Boston, Koln. Brill 1998

- Sudhoff K. The literary remains of Paracelsus. In Garrison F, ed. Essays in the History of Medicine. Medical Life Press: New York, 1926

- Trevor-Roper H. The Paracelsian Movement. In: Renaissance Essays. London 1985, pp.149-99.

- Pagel W, Rattansi P. Vesalius and Paracelsus. Cambridge Univ Press 1964;309-328 https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/BB50FE88A7122B0FD602742ABCC3E8AE/S0025727300029781a.pdf/vesalius-and-paracelsus.pdf

- Hargrave John. The Life and Soul of Paracelsus. London, Gollancz 1951.

- Eknoyan G. On the contributions of Paracelsus to nephrology. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996;11: 1388-1394.

- Sigerist H ed. Four Treatises of Theophrastus von Hohenheim Called Paracelsus. Baltimore Johns Hopkins Press. 1941

JMS PEARCE is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine

Winter 2021 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply