Stephen Martin

Durham, UK, and Thailand

|

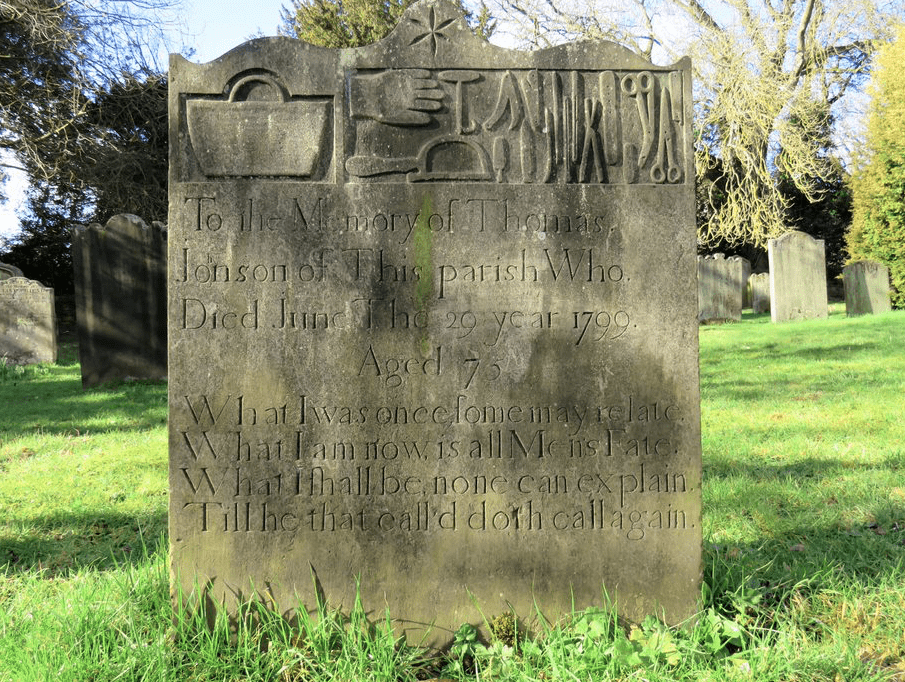

| Fig 1. Monument to Thomas Johnson, Brancepeth. Source: photo © author. Public domain for non-commercial use |

In the churchyard of St. Brandon in Brancepeth1 village, County Durham, UK, is an unusual headstone monument.2 (Fig 1) Dating to the very last year of the eighteenth century, it has three sections, including the name and dates, and then a cryptic verse pertaining to judgment. Carved in relief within two panels at the top are a medical bag and a set of surgical instruments. The inscription is:

To the Memory of Thomas.

Johnson of This parish who.

Died June The 29 year 1799.

Aged 75

What I was once, fome may relate.

What I am now, is all Men’s Fate.

What I fhall be, none can explain.

Till he that call’d doth call again.

It is a high-quality carving in carefully selected hard sandstone, which has survived in fine condition with no significant weather erosion. Six of the instruments even have neatly drilled, realistic rivet holes. Two defects in the scissors match the size of one on the frame of the group and appear to be artifacts from the stone’s geological formation. It is interesting that the stonemason was still using the medieval style of f for s at the beginning of words, which died out in the coming decades. The script is beautiful, with hints of some semi-literacy from the corrected surname spelling and erratic use of capitals and full stops. Mr. Johnson appears to have composed the text himself, with a notably modest avoidance of declaring his profession. Literally and figuratively, he put his instruments above his persona.

|

| Fig 2. Detail, Surgical Instruments of Thomas Johnson. Source: photo © author. Public domain for non-commercial use |

|

| Fig 3. Folding fleam set, by Wingfield Rowbotham and Wade, after 1818. Source: © Nigel Pierlejewski, Piers Antiques, Curios and Collectibles, Penclawdd, Swansea and reproduced here with his kind permission |

The instruments touch the top or bottom of the frame. (Fig 2) With this as a reference, these are discussed working around clockwise, starting with:

1. The bag. This is of a grip-style, of unusual trapezoid shape for medical use. The Gladstone bag we all expect was a relatively recent late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century proliferation. There appears to be a lock carved as three central horizontal bars.

2. The glove is remarkable as these were rarely used at the time. The mason carved a circular indentation representing the collapse of a glove not in use. Leather looks the most likely material, judging from the bulk of the item, which is presumably realistic, given the mason’s capacity for delicate carving in the other instruments. If it was leather, protection of the surgeon from injury and sepsis may have been intended. Before bacterial infection was understood in the mid-nineteenth century, it was still obvious that sepsis was a dangerous and often fatal condition. There was an idea that poisonous miasma could transfer from the patient to the surgeon.3 Those who were interested were onto something. In 1758, the Lübeck obstetrician Johann Julius Walbaum (1724-1799) protected his hand with a damp sheep’s cecum, as a barrier in the obstetric procedure of turning a baby within the womb.4 Thomas Johnson was an exact contemporary of Walbaum and it is plausible that he somehow learned from continental Europe. Early gloves of cotton and silk were also used, but not until 1899 did Halstead employ the first surgical rubber glove in Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore.

3. Skin retractor—it has an unusual transverse handle and end probe. It is quite short in proportion to the folding scalpels, which gravitates away from other kinds of medical hooks. Large laparotomy retractors did not arise until von Langenbeck’s experience with bullet wounds in the mid-nineteenth century.5

4. Curved folding scalpel—this has a hinge rivet and case end rivet, with an opening lever to keep the fingers away from the blade. Folding instruments were common in eighteenth-century sets.

5. Straight folding scalpel—again, with the same rivets and lever.

6. Rigid straight scalpel.

7. Tweezer forceps.

8. Amputation knife—this has a four-rivetted handle. A spatula is also a possibility for this, but there would normally have been a large knife to work with the amputation saw and this fits it.

9. Angled scissors.

|

| Fig 4. Barge-flag: achievement of arms of the Worshipful Company of Barber-Surgeons of London. Gouache on cloth. Credit: Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) |

10. Folding fleam set—for blood-letting. Note the expanded end to house the side blades as in Figure 3, and another opening lever. Stylized fleams appear on the coat of arms of the Worshipful Company of Barber Surgeons granted by Elizabeth I in 1559. (Fig 4) They are the white objects with a blade and handle on either side of the chevrons. Galen’s idea of balancing the humors with blood-letting was about to fade in 1799. The Company survives today as a charitable organization, retaining the motto De Praescientia Dei, meaning From God’s Foresight.

11. Straight scissors.

12. Sharpening stone—notably this object has no rivet. Crucial for neat cutting.

13. Bullet forceps—not just for bullets.

14. Tweezer forceps—with a shorter handle.

15. Urethral Sound—probably not a curved scalpel, as it has heavier carving than the delicate knife to the side.

16. Large syringe—This was hard to identify, but, on magnification, the left-hand side of the plunger handle is cut as a notch, though not as distinctly as the other syringe.

17. Small Syringe

18. Amputation saw—with a bulbous handle, bow-framed to accommodate the limb tissue bulk and minimize damage, having five carved serration notches to the blade and a blade tensioner screw. A similar one survives in a set at the Royal College of Surgeons. (Fig 5)

|

| Fig 5. Mid to late eighteenth-century British amputation set. Source: photo © Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, RCSIC/I 51-f, reproduced here with kind permission |

Apprentice barber surgeons were bound to their masters for training by a contract, handwritten on paper or parchment, which was cut in two in a chaotic line—the indenture. This jigsaw symbolized and proved the agreement between the two specific individuals. The Newcastle upon Tyne Barber Surgeons’ Company archive6 describes a Thomas Johnson having withheld half the indenture of his apprentice William Thornton. The affair went on from 1779 to 1784. Johnson tried to keep Thornton bound to him as master surgeon and barred him from being free to work. This was apparently in an effort to have him work for him for longer because the apprentice had taken time off to travel, which was allowed for study in the last year. The company ruled that Thornton’s apprenticeship was complete and he was granted freedom from the indenture. Sadly though, for the apprentices, the surgeons also ruled that the Company had to approve all such travel in the future. Apprentice surgeons were no longer free to take study leave as they wished in the last of their seven years of indentured training. This can be interpreted either as a well-meaning effort to prevent skiving, or an early example of protective managerialism, getting more time from trainees with escalating medical bureaucracy.

It was common to refer to judgment in eighteenth-century philosophizing about mortality. Was Johnson ruminating anxiously on his maker being harsh to him, because he was unfair to his junior surgeon? Enough said. We may never know if we have the right Mr. Johnson. There is a fair chance of there being two surgeons with this same, common name, so we do not wish to smear the deceased man of Brandon as a mean and exploitative employer beyond reasonable doubt.

Johnson could have worked in Newcastle and retired to family in Brancepeth. Further records may yet come to light on this; we found nothing. It is common in early parish record searches to draw a blank, especially with transcription errors and spelling variations. Also, Thomas Johnson’s dates precede the various Northeast Trade Directories, which began in the Regency period. No Thomas Johnson is recorded in the Durham Trade Guild lists, either, who fits the dates of interest.7

|

| Fig 6. Detail, Monument to James Borthwick, Greyfriars Kirk, Edinburgh. Source: photo © Kim Traynor. (CC BY-SA 2.0) |

It is rare, but not unique, to see surgical instrument emblems carved on stone monuments. The eroding tomb of James Borthwick (1615-1675) (Fig 6) in Greyfriars Kirkyard, Edinburgh, from 1676, has instruments arranged in bundles, resembling Palladian motifs and the musical instrument groupings of the contemporaneous carver Grinling Gibbons. Borthwick jointly initiated the role of the Surgeon-Apothecary and taught anatomy.8

The 1719 wall monument (Fig 7) to Thomas Havers (1659-1719) outside Stoke Holy Cross Parish Church, Norfolk,9,10,11 has seven surgical instruments on a baroque panel in good condition, including an impressive, two-part catheter and introducer. He specialized in bladder stone extraction. Havers, not shy of polymathy, was also the local vicar and evidently his combined income could budget for a fine memorial.

Johnson’s headstone is a lot less architecturally sophisticated, but it is true to his professional life, as if his instruments are neatly laid out on a tray or a cloth. His stone still shows some style, with a serpentine top edge and a central star of six rays. Was this star Masonic, an Old Testament homage, or both? It could also have been an allusion to the Venerable Bede’s Christ is the morning star, from his commentary on the Book of Revelation, written in AD 710. Bede’s tomb is in Durham Cathedral, three miles from Brancepeth. From Bede’s writings, besides being a theologian and immensely knowledgeable historian, he was very interested in medicine from his monastery at Jarrow, County Durham.12

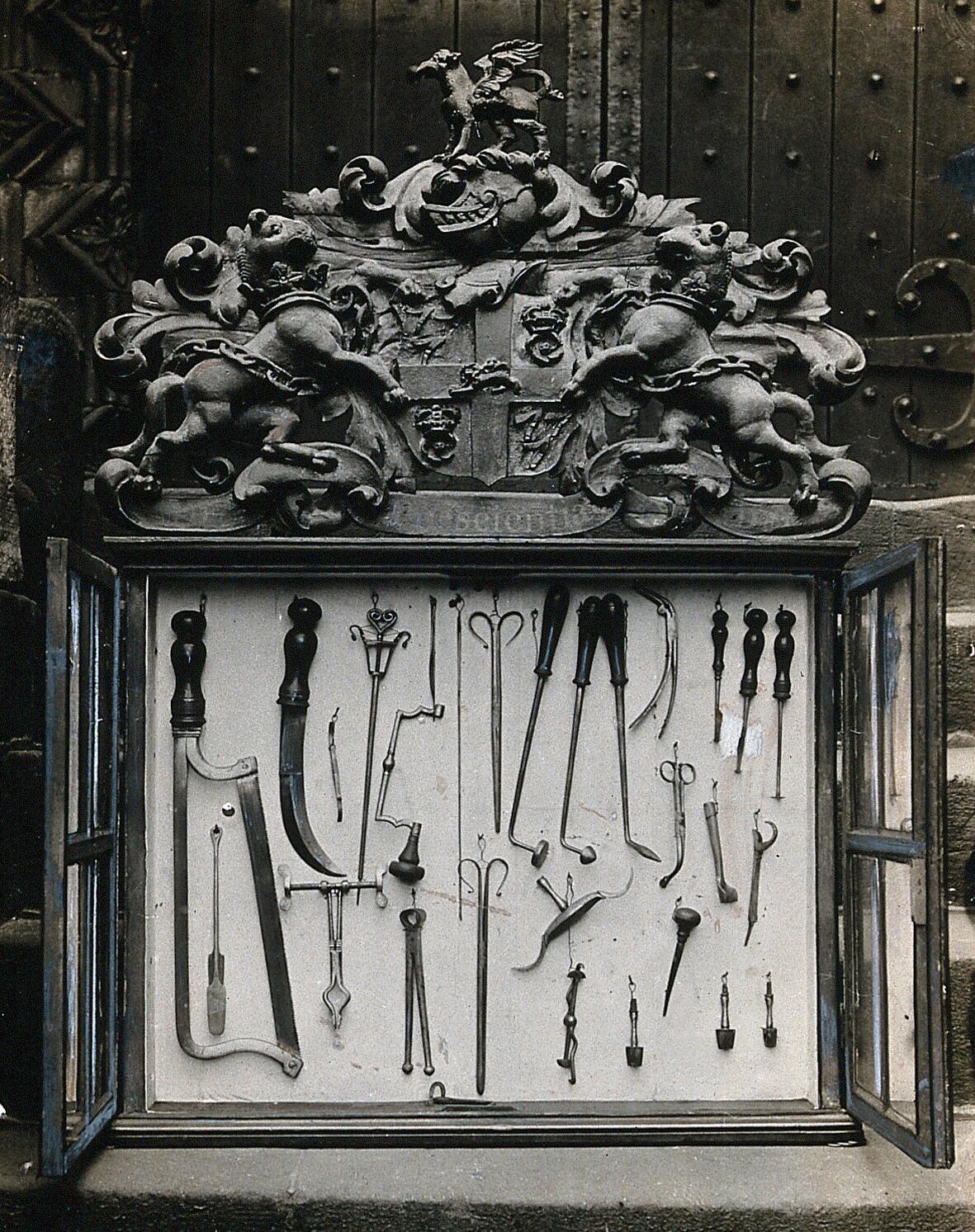

Newcastle upon Tyne still has an early set of barber surgeons’ instruments (Fig 8) in a case with the company’s arms carved in relief.13 The wood carver missed out the chevrons. These instruments are of different ages and styles, possibly originating from several surgeons. They were apparently for lending out14 and can be viewed as an emblem of the core importance of instruments. The value of Johnson’s monument, even in stone, is the record of a full armamentarium of surgical instruments belonging to one of the last individual barber surgeons. It might also be the oldest image of a surgical glove, perhaps more for armor than pre-conceived asepsis. This, as Johnson could have put it, still remained largely in God’s foresight.

|

|

| Fig 7. Detail, Surgical instruments on the monument of Thomas Havers DD, Stoke Holy Cross. Source: photo © Dr. Michael Fordham of Poringland Archive, reproduced here with his kind permission. | Fig 8. The Barber Surgeons’ Guild of Newcastle: surgical instruments in an armorial case. Photograph, ca. 1926. Credit: Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) |

References

- https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1311239 Brancepeth means Brandon’s Path, the lane to the Church of St. Brandon. This is St. Brendan of Clonfert, convincingly described as sailing to volcanic Iceland in the sixth century. The idea that he reached America seems to be a romantic notion, sadly with no good evidence. However, many church dedications in Britain are associated with places of the patron saint’s activity.

- Church burial reference: Old graveyard, section D 19, no 296, d 1799. The site is thirteen meters to the south of the church, from where the exterior aisle wall joins the center of the tower’s south side.

- Ellis, H. Surgical gloves. J Perioper Pract 2010 Jun; 20(6), pp. 219-20.

- Stanoslawski, N. Bakterielle Translokation durch Perforationen von chirurgischen Handschuhen unter realen Operationsbedingungen. Dr Med thesis, Ernst-Moritz-Arndt Universität, Greifswald, 2013. https://epub.ub.uni-greifswald.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/1285/file/Dissertation_Stanislawski_Bibliothek.pdf Also see Rutkow, IM. Surgery. An Illustrated History. Mosby, St .Louis, 1993.

- He is also credited with inventing the house officer system of residency training.

- Tyne & Wear Archive. GU.BS/24. Correspondence concerning apprenticeships, 24 September 1783 – 10 August 1840. Also discussed in Meades, C. https://cameofamilyhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Guild-Records.pdf

- http://reed.dur.ac.uk/xtf/data/pdf/DCGBarbers/DCGBarbers.pdf

- Cresswell, CH. The Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. Oliver & Boyd. Edinburgh, 1926, p.36.

- Pevsner N, Wilson B. The Buildings of England. Norfolk 2; North-West and South. Yale University Press, Newhaven and London, 1999, p. 673.

- https://www.poringlandarchive.co.uk/stoke-holy-cross/norwich-road

- Recording archive for public sculpture in Norfolk and Suffolk: http://www.racns.co.uk/sculptures.asp?action=getsurvey&id=609

- Gardner, R. Miracles of healing in Anglo-Celtic Northumbria as recorded by the venerable Bede and his contemporaries: a reappraisal in the light of twentieth century experience. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1983 Dec 24; 287 (6409), pp. 1927–1933.

- Now in the Discovery Museum collection, Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums. The early photograph held by the Wellcome Collection was taken on the steps of Newcastle’s Norman castle, as the Society of Antiquaries used to house the instruments in the castle’s Black Gate Museum until the 1980s.

- Pybus, F C. The Company of Barber Surgeons and Tallow Chandlers of Newcastle-on-Tyne. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, Section of the History of Medicine. 17 December 1924, pp. 7-16. Online link: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/003591572902200303.

STEPHEN MARTIN is a semi-retired neuropsychiatrist, Honorary Professor of Psychiatry at Chiang Mai University, and Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland.

Leave a Reply