|

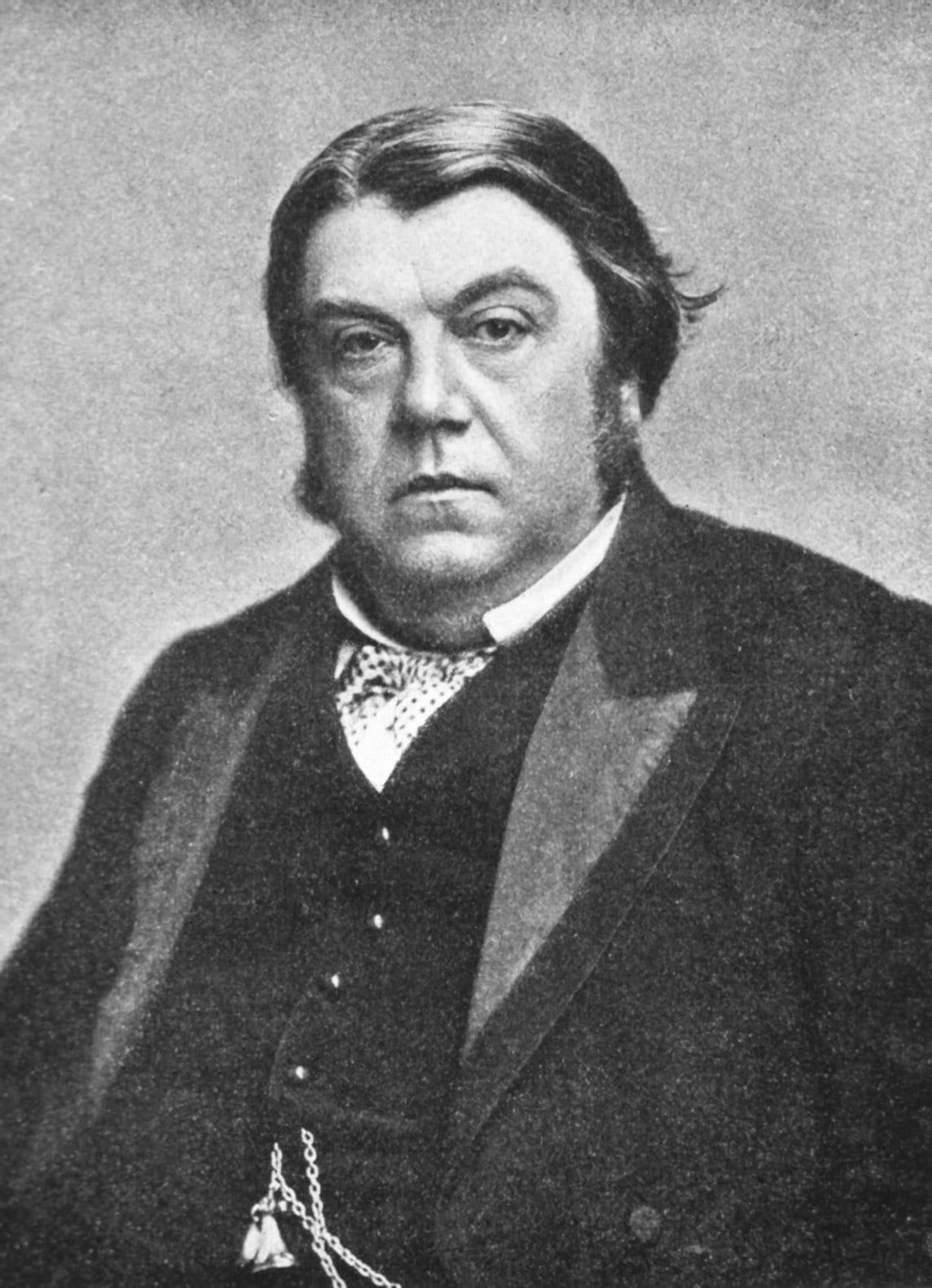

| Robert Lawson Tait. via Wikimedia. |

Robert Lawson Tait was fifth in a dynasty of pioneers who helped transform surgery from a primitive craft to a sophisticated life-saving art. They all worked for a time at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary—James Syme (the “Napoleon of Surgery”), Robert Liston (“time me, gentlemen”), James Simpson (“made childbirth painless”), and Robert Lister (“antiseptic surgery”)—and with the exception of the latter were all Scotts.1

Tait himself was born in 1845 in Edinburgh, entered the University on a scholarship in 1860, studied art for one year, then changed to medicine.2-6 He was apprenticed for six years to Alexander McKenzie Edwards, a lecturer in surgery4 and upon graduation acted as his assistant. While in medical school he lived in the home of James Simpson and later also became his assistant. Because of their striking resemblance, both being short, heavy-set men with thick necks, heavy shoulders, and large heads, it was rumored that Tait was Simpson’s natural son.4 This is generally believed to be unlikely, but be it as it may, Tait was greatly influenced by James Simpson, whom he idolized and whose aggressive style he strove to emulate.

After graduation from medical school in 1867, Tait worked for three years as house surgeon in Wakefield, a market town in Yorkshire.2-6 Here he began his career as a surgeon of women’s diseases, performing during his stay five operations for removing ovarian cysts.2-6

In 1870 Tait took over a surgical practice in Birmingham.2-6 He worked assiduously to promote himself, joined medical societies, and frequently debated. He became a member of the staff of a local newspaper and wrote leading articles regularly to augment his funds and further his reputation.2-6 He gave lectures and became known in the local community and to local professors. He passed the examination for fellowship in the Royal College of Surgeons and aggressively campaigned to establish a women’s hospital.

The hospital was founded in 1871 in a three-story house and he was appointed one of the three attending surgeons. It was there that he performed his first gynecological operation. This was followed by a veritable surgical avalanche, and within a few years he became one of the greatest of the early abdominal surgeons. By 1884 he had performed 1,000 operations on the abdomen, by 1888 a further 1,000, and another 2,000 in the following ten years, with a lower than 10% mortality, using a mixture of chloroform and ether.2-6

There were no operating rooms in those days. A table would be wheeled into the patient’s room and Tait, wearing an apron, would operate with scrupulous cleanliness and the smallest number of instruments. He insisted on absolute asepsis, not using Lister’s carbolic spray or other antiseptics, but sterilizing every dressing, wearing rubber gloves, and making sure that the walls and floors were scrubbed clean with carbolic acid. Before closing the abdomen he would wash the peritoneum with large amounts of water as a means of maintaining sterility and achieve hemostasis.3

He was first to tread where others feared to enter—into the abdomen.2-6 Many of his operations were historical firsts,2 such as in 1872 when he removed a chronically infected ovary or in the same year when he removed both ovaries to “arrest menstrual hemorrhage due to uterine myoma.” In 1873 he excised a dead extrauterine fetus but did not remove the placenta because of the risk of severe hemorrhage.6 In 1874 he did his first hysterectomy for a uterine fibroid or myoma that weighed eleven pounds. Throughout his surgical career, he continued to drain pelvic abscesses, remove infected organs, excise large ovarian cysts, and operate to staunch bleeding. He did oophorectomies for abdominal pain and for excessive bleeding. He saved countless lives by introducing salpingectomy for ectopic pregnancies and in 1883 operated for a ruptured ectopic pregnancy and saved the patient’s life. He performed one of the earliest appendectomies. In 1883 he was one of the early pioneers of gallbladder surgery, removing gallstones and, in 1879, performing one of the earliest cholecystectomies. In 1880 he operated on the liver to remove a hydatid cyst of the liver with a very large amount of cystic material. He was the first to describe the association between ovarian fibroma and pleural effusion (Meigs syndrome).7

Tait broke with Lister on the issue of antiseptic surgery and never used the carbolic acid spray except to clean the wall, the floors, and the instruments and materials in his operating room.2-6 He did not believe in the existence of bacteria and later would make derogatory comments about Lister’s antiseptic system of surgery.

Throughout his career, Tait published extensively. At age twenty-three he described minute tubercles on the surface of the lungs of swallows and wrote on tapeworms in birds. Between 1873 and 1888 he published extensively on diseases of women and specifically of ovaries.2-6 Notably in 1877 he authored an influential textbook on Diseases of Women.2-6 In the same year he wrote An Essay On Hospital Mortality, in which having studied hospital mortality for fifteen years he concluded that mortality was lower in small hospitals and that any hospital with more than 100 beds presented a grave danger. In this he agreed with Florence Nightingale that fewer people would die if left at home than if exposed to the risks of being in hospital. In 1879 he wrote about operations for repair of the perineum.

Tait was a controversial figure but probably the most skillful surgeon of his time. To his distress, the success of his operations prompted other surgeons to perform abdominal surgeries and remove normal ovaries. He took great pains to correct this misunderstanding, but for a time was interested in removing essentially normal ovaries for the treatment of neurosis in women, a procedure of female castration popular in America for a time but soon condemned as inappropriate. He seems to have believed in “ovarian epilepsy” and reported that excision of the ovaries in a few cases with severe epilepsy was followed by great improvement but did not press this approach.

He became professor of gynecology at Queen’s College in 1887 and was instrumental in it eventually becoming part of the newly founded University of Birmingham. He was heavily involved in the British Gynaecological Society, the British Medical Association, the Medical Defense Union, and the local city council, and was often seen as antagonistic and overstepping his place. He had wide interests and was a member of various health committees and societies of anatomy, art, natural history, philosophy, and design. His work was recognized in America and he received honorary degrees or fellowships from various colleges and universities. He attempted to enter parliament but was unsuccessful.

He charged up to one thousand pounds for a consultation and his income was over 20,000 pounds a year,2 but he treated many poor people for free. He became exceedingly rich, owned four houses, but was reportedly mean about small sums of money.2 In 1892 he was offered a baronetcy but declined.5 He was a hard fighter, used rough language, was ill-tempered and difficult to live with but kind to patients and animals. He was an avowed antivivisectionist, a strong and outspoken opponent of the use of animals for research, instruction, or practice. He and his wife were exceedingly fond of cats and he made scientific observations that he published periodically in Nature. He noted that some white cats, and only white ones, had a congenital form of deafness due to an abnormality in their tympanic membrane.8 He argued that cats, squirrels, and other animals had developed bushy tails in order to preserve body heat and on winter nights would lay them over their feet as one would a blanket.9 He was impressed with the “intellect” of cats and noted that his own cat developed a mutual dislike with a visitor to his house, and although it had clean habits would always “make a mess” in their bedrooms.10

Tait was a bon viveur who loved good food, alcohol, and cigars. At age fifty he became embroiled in a paternity suit and a libel action, became financially embarrassed, and had to sell off his country house, his houseboat, and his yacht.4,5 In 1897 he had surgery for the removal of a urethral calculus and nearly died under anesthesia. In 1889 he developed renal failure and uremia. A few hours before his death he insisted on smoking a cigar, saying it would be his last.2-6 He is remembered as the first surgeon to enter the abdomen with impunity, and has appropriately been regarded as a father of aseptic surgery and of gynecology.

References

- For further notes on these distinguished surgeons please see Dunea G. in the Sections on Surgery or in Birth, Obstetrics, and Gynecology.

- Royal College of Surgeons of England: Tait, Robert Lawson (1845-1899), 27 November 2012.

- Harley Williams: Masters of Medicine, page 118, Pan books Ltd, London, 1854

- Flack IH: Lawson Tait. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1948;2(4): 165.

- Glen J & Irvine LM. Dr Robert Lawson Tait: The forgotten gynecologist. J. Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 2011; 31: 695.

- Laman A. Gray: Lawson Tait (1845-1899) The Innominate society. www.innominatesociety.com

- Christopher C: Lawson Tait: the rebellious surgeon (1845–1899)

- Tait, L: Notes on deafness in cats. Nature 1883; 29: 164.

- Tait, L. The Uses of Tails. Nature 1879; 20:603.

- Tait, L. Intellect in Brutes. Nature 1879;20:147.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply