|

| German zoologist Fritz Schaudinn. Source Fritz Schaudinns, Verlag Leopold Voss, Hamburg und Leipzig 1911. Via Wikimedia. |

Beginnings

The origins of syphilis have been subject to much debate. The disease has been claimed to be thousands of years old and originally to have evolved from yaws. Generally mistaken for leprosy and not recognized as a separate entity, it might have taken the form of a mild disease, prevalent in societies whose inhabitants paid more attention to personal hygiene.1 More popular has been the view that syphilis was brought to Europe by the sailors of Christopher Columbus and disseminated by the French soldiers of Charles VIII during their brief occupation of Naples in 1495. It then quickly spread to all corners of Europe as a particularly malignant sexually transmitted disease that acquired early on an infamous and disreputable name. The various populations of Europe blamed each other, as well as the Jews, for causing the disease, which became variously called the French disease, the Neapolitan disease, the German disease, the Spanish/Castilian disease, or (by Muslims) the Christian disease.1

Syphilis received its name from Girolamo Fracastorio of Verona, author of a poem in which the shepherd Syphilus offended Apollo and caused him to unleash on the world a hideous disease bearing his name.2 Paracelsus was one of the first to treat syphilis with mercury, which was toxic.3 Bismuth was introduced in 1884 and had fewer side effects. Paul Ehrlich, in his search for the magic bullet, introduced arsphenamine (Salvarsan) in 1908 and received the Nobel Prize,4 as did Julius Wagner-Jauregg in 1917 for treating patients with neurosyphilis by giving them malaria.5

On the diagnostic front, complement fixation or antibody tests were developed by Bordet and Gengou in 1901 and by Wasserman and colleagues in 1906.6 This was the era when scientists were discovering the bacterial causes of many diseases and often attached their name to them—sometimes in a Latinized form. It was also when the discovery of powerful microscopes allowed Fritz Schaudinn to see the organism causing syphilis.

Fritz Richard Schaudinn7-9

Schaudinn is best described as a zoologist. Born in 1871 in what formerly was East Prussia, he matriculated in philosophy in Berlin and then switched to natural sciences, especially zoology. He went to Bergen in Norway to study the Arctic fauna, became a private dozent in Berlin, went back to the Arctic, and then was assigned to a town in Dalmatia. There he studied malaria, amoebiasis, and treponemas. Returning to Germany, he became director of an institute of protozoology and was given the task to study hookworm disease, which at the time was afflicting German miners. He then studied syphilis as part of a scientific team that came to the dubious conclusion that the same common bacterium was causing scarlet fever, smallpox, foot and mouth disease, and syphilis.

A joint clinical and parasitological investigation was continued with the help of the dermatology clinic the Charité hospital in Berlin, where Schaudinn collaborated with the dermatologist Erich Hoffman and the bacteriologist Fred Neufeld. Using a state-of-the-art microscope he saw against a dark background in the fluid of a syphilitic papule a pale spiral bacterial rod among many other organisms present. He called it Spirochaeta pallida and at first thought it was a saprophyte, such as often found in non-syphilitic lesions such as condylomas. On March 10, 1905, Schaudinn and Hoffman reported finding the Spirochaeta in syphilitic lesions without claiming it necessarily was the cause of the disease.7-9 In May they presented their finding to the Berlin medical society, cautiously suggesting this could be the etiologic factor of syphilis. The paper was not well received and the meeting was eventually adjourned by the chairman “until another agent responsible for syphilis engages our interest.”9

Several other investigators also found the spirochete in syphilitic lesions but were not able to grow it in culture. Meanwhile, Schaudinn took a leave of absence from the ministry of health in order to work in the new protozoology laboratory in Hamburg. He developed a rectal abscess and died from septicemia the following year.

|

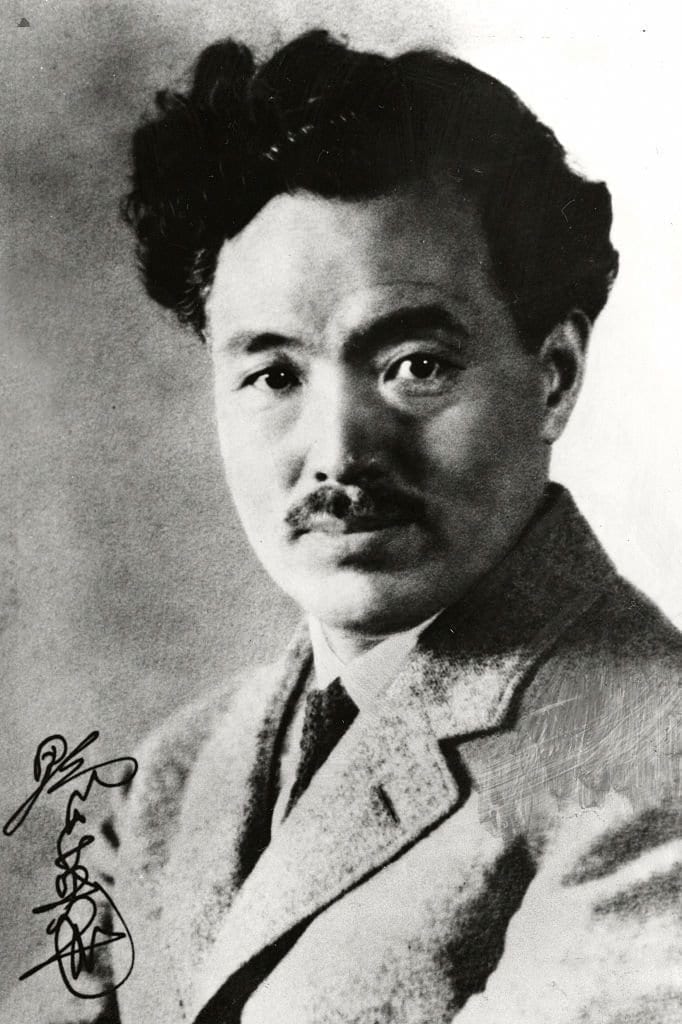

| Portrait of Hideyo Noguchi. Unknown author. Taisho era. Via Wikimedia. |

Hideyo Noguchi

The scene now shifts to an illiterate poor boy living with his mother in a small village in northeastern Japan and remarkable for his ability to work hard, sleep little, and seize the right opportunity in life.10 As a young boy he had upset a simmering pot of rice, sustaining a severe injury to his left hand that the village doctor was unable to treat. The boy, who later changed his name to Hideyo Noguchi, was sent to an elementary primary school and taken under the wing of a teacher who recognized his potential. Thanks to generous contributions from his teacher and his friends, he underwent surgery and recovered about 70% function and mobility of his left hand. Through the contributions and influence of a physician school inspector, the boy was able to attend school, where he had to walk three miles each day in summer and winter to get there. He was adopted by the physician who took him on as an assistant and offered him opportunities to read books and also to use a microscope. At age twenty, Noguchi walked twenty miles on foot to Tokyo, got a job cleaning oil lamps at a medical school, and eventually was admitted and graduated as a doctor. There he met Simon Flexner, then visiting professor, who made the vague promise that he would help him if he came to America.

Noguchi then became a quarantine officer, spent some time in China working on plague, and eventually secured a passage to America. There he obtained a job with the aging Dr. Weir Mitchell, whose interest in his retirement was to study snakes and make antidotes against their poison. On that basis, Noguchi was awarded a fellowship to study in Europe and eventually was hired by Simon Flexner as his assistant at the newly formed Rockefeller Institute. With his experience he was able to develop a method to culture the silver spirochete discovered by Schaudinn, using a special culture medium in a tubular device five feet tall nearly filled with blood in which the organism would grow. It was thus that Noguchi made the vital contribution that this spirochete could be transmitted from one person to another, thus fulfilling Koch’s postulates. He also demonstrated the presence of this spirochete in the brains of patients with neurosyphilis. Later he switched his interests to other diseases and sadly died in Africa while trying to develop a vaccine against yellow fever.10

Resolution

The final drama in the fight against the pallid spirochete took place in England and has been much written about.11-16 It centers on Scottish-born Alexander Fleming, who in 1922 had already discovered lysozyme, a chemical capable of destroying bacteria. On returning from a vacation in 1928, he found several culture plates contaminated by a mold that was killing the staphylococci around it. He grew some of the mold in a liquid broth and found it contained a substance capable of destroying many pathogenic organisms and suggested it might be an ideal antiseptic.11-14 He was ignored and nothing happened until World War II when its manufacture and mass production became possible owing to the work of Sir Howard Florey and his research team in Oxford.15,16 Penicillin became the therapeutic agent that could kill the Treponema pallidum, so that syphilis is no longer one of the major scourges of mankind. It has not been completely eliminated from the face of the earth, and it undergoes periodic resurgences due to increased international travel and changes in societal behavioral patterns, so that it is down but not completely out.17

References

- Tampa M, Sarbu I, Matei C et al: A brief history of syphilis. J Med Life 2014; 7: 4.

- Dunea G: Fracastorius, the man who named syphilis. Hektoen International, [Infectious diseases section. 6:1. Winter 2016]

- Sonoc AG. Paracelsus: physician and alchemist. Hektoen International. [Art flashes section, Winter 2014]

- Dunea G. Paul Ehrlich: from aniline dyes to the magic bullet: Hektoen International. [Science section, Fall 2018]

- Karamanou M, Liappas I, Antoniou C, et al. Julius Wagner-Jauregg (1857-1940): Introducing fever therapy in the treatment of neurosyphilis. Psychiatriki 2013;24: 208.

- Bialynicki-Birula R: The 100th anniversary of Wassermann-Neisser-Bruck reaction. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26(1):79-88.

- Lennox Thorburn A: Fritz Richard Schaudinn, 1871-1906. Protozoologist of syphilis. J. Vener. Dis. 1971: 47: 459

- Editorial: Schaudinn: Protozoologist of syphilis. JAMA 1965:192.

- De Souza EM: A hundred years ago, the discovery of Treponema pallidum. Ann Brazil Dermatol 2005;80:547

- Harley Williams: Hydeyo Noguchi, in Masters of Medicine, p220, Pan Books, Ltd, London,1954.

- Ugokwe E: Penicillin’s unique discovery. Hektoen International, [Infectious diseases section 5:4, Fall 2013]

- Kingston W: Chance in the origins of antibiotics. Hektoen International, [Infectious diseases section 6:3 Summer 2014]

- Radhakrishnan J: Sir Alexander Fleming: A microbiologist at work and play. Hektoen International, [Infectious diseases section. Winter 2020].

- Slingerland AS and Brown K: Mary’s Hospital, birthplace of penicillin. Hektoen International, [Hospitals of note section, 11: 2, Spring 2019]

- Cracolici V: Lord Howard Florey and the use of visual art in medicine. Hektoen International, [Art section, Summer 2016]

- Philip John Ryan: Lord Florey and the other war. Hektoen International. [Infectious diseases section 8:3, Summer 2016]

- Schmidt R, Carson PJ, and Jansen R: Resurgence of syphilis in the United States. Infect Dis (Auckl), 2019; 12, Oct 16.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Winter 2021 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply