Saty Satya-Murti

Santa Maria, California, United States

|

| Figure-1: Timothy Leary at work, circa 1920. Credit: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Source |

Most people know the name of Timothy Leary as an American counterculture guru and psychologist who had a massive following in the mid-twentieth century. He invoked the names of Gandhi, Jesus, and Socrates as his martyred models; was associated with Aldous Huxley, John Lennon, and Jack Kerouac; and fissioned the country’s sense of morals and mores. He was a fugitive, hiding in Algeria and Switzerland to deflect Richard Nixon’s wrath, and earned the label of the “most dangerous man in America” even as he predicted that “there will be a statue of me” in gratitude for his work to society. He expected a global spiritual conversion enabled by the use of LSD (Lysergic Acid Diethylamide) and was the author and subject of many books and articles.1

Another Timothy Leary (1870-1954) from a century ago is, however, unfamiliar to most. The controversies generated by his later namesake, counterculture Timothy Leary (1920-1996), subdued recognition of the former. Did they share anything in common besides a name?

The elder Leary was born in May 1870 as one of eight siblings to a Waltham, Massachusetts grocer. A graduate of Harvard Medical School (1895), he was later a professor of pathology at Tufts College Medical School from 1900 until his retirement in 1929. (Figure 1) He served as a pathologist (1898-99) in charge of the Vaccine Corps at the U.S. Army Hospitals in Ponce, Puerto Rico and Santiago, Cuba. His wife, Olga Cushing Leary (1878-1960), was also a pathologist at Tufts until 1929. Subsequently, she ran a first-of-its-kind independent clinical and tissue pathology laboratory with her husband in Boston. Of their three children, two were physicians. In later life, osteoporosis and back pain confined Leary’s activities, but he continued to pursue his professional interests and his hobbies of art, gardening, and history.2

|

|

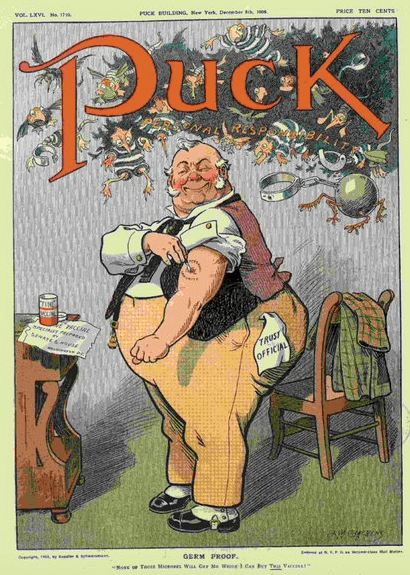

Figure-2: “None of those microbes will get me while I can buy this vaccine!” A 1909 Puck Magazine satirical cartoon depicting a vaccine’s ability to protect from diseases and bestow political immunity for evading personal responsibility. Artist: L.M. Glackens (1866-1933). Credit: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Source |

Leary as vaccinologist

The Vaccine Corps was a cadre of trained persons in charge of administering vaccines in Cuba and Puerto Rico during the mid-to-late 1800s. One of these was the Central Vaccine Board of Cuba that promoted smallpox vaccinations.3 It is likely that Leary served in the Spanish-American War as a physician-vaccinologist before returning to Boston to take up a faculty position at Tufts Medical College in 1900.

Success with smallpox prevention elevated the value of vaccines. In the early 1900s, enthusiasm kindled hopes that vaccines could cure cancers, typhoid, cholera, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases. The typhoid vaccine was probably the most effective in the military.4 Leary had begun his “antitoxin” (vaccine) against pneumonia and typhoid circa 1909. Initially, he was cautious because of his “too small” sample size and had urged about “ten years” of study before promoting his discovery.5 Opposition for vaccination as a dangerous, “unacceptable invasion of personal liberty” was also equally strong. These antipodal constructs of individual choice vs public safety generated piquant debates then, as they still do now.6 Drawing upon anecdotes and testimonials, newspapers touted the power of vaccines. The now defunct humor magazine PUCK (1871-1918) promoted and caricatured an imaginary vaccine’s protective power against illness, and consequences for irresponsibility and venality. (Figure 2)

This milieu was an apt setting for the entry of a vaccine to prevent mortality and morbidity, especially from pneumonia, during the 1918-19 influenza pandemic.7 Influenza itself was erroneously attributed to Pfeiffer’s (Hemophilus Influenzae) Bacillus; knowledge of its viral origin had to wait till 1933. The essential ingredients of the 1918 vaccines were bacterial cultures from influenza patients grown in vitro, extracted, and sterilized. Several such vaccines were available, and the one from Leary was a mix of three strains: “Carney” from a nurse’s nostrils, “Navy” from Chelsea Naval Hospital, and “Devens” obtained from two other physicians. A 1918 article gave detailed accounts of vaccine preparation, sterilization, and dosing for both prevention and reduction of illness severity in all but “moribund cases.” Leary himself claimed that “marked amelioration of symptoms” occurs after vaccination.8 Among known recipients were about 2,000 healthcare personnel in New York, 2,188 in Tewksbury Infirmary, Massachusetts, about 20,000 in San Francisco, 39,000 in Newark, and several in San Quentin Prison.9–11 Another vaccine from the University of Pittsburgh was also available.7,12–14 Several reports about these vaccines pointed to variable or questionable beneficial results. A comprehensive evaluation was difficult because of permissive methodologies and heterogeneity, inherent in studies from 100 years ago. Recent reviews of data from past studies, however, acknowledged that the potential to prevent and reduce secondary pneumonia did exist.15,16 Likewise, the lax methodologies of early studies notwithstanding, convalescent plasma also may have conferred some benefit.17 Thus, it is possible that both the vaccines of that day and the convalescent sera were helpful in some circumstances. This intent to relieve suffering is noble and laudable, even if it lacked the sophistication available to us today.

|

|

Figure-3: Leary teaches Pathology at City Hospital, circa 1920. Credit: Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University. Source |

Leary as pathologist and medical examiner

Leary served as chair of pathology for twenty-nine years. The department gained prestige during his tenure for distinction in teaching and the development of a testing laboratory. His reputation brought in increasing numbers of applicants and needed revenue. (Figure 3)

As a medical examiner for Boston and Sussex County, his forensic skills at detecting the inapparent culprit received national attention. He investigated the infamous Boston Night Club Fire of 1942 that claimed 491 lives. He attributed many deaths to poisonous emissions, carbon monoxide, and flames. He was also the pathologist involved in the autopsy of a Cincinnati Reds catcher’s suicide. 2,18,19

Control of infectious diseases improved throughout the early twentieth century as their causes were better understood. The burden of morbidity began trending towards non-infectious chronic illnesses. Medical sciences entered the dawn of the “golden age of medicine” (1930s to 1980s). Its energies and resources tilted away from social to technological determinants of health.20,21 Leary commented on the increasing longevity of the population and chronicity of non-infectious diseases.22 His focus shifted from proximate (immediate) causes of morbidity to distal and chronic accretive determinants of ill-health. He believed that the origins of coronary artery pathology were traceable to habits, living circumstances, and dietary and alcohol “excesses.”

Following retirement from Tufts in 1929, he focused his attention on the study of atherosclerosis. Based on his findings of nearly 15,000 autopsies, he made seminal observations about atherogenesis and the histopathology of atherosclerosis. His study of cholesterol-fed rabbits and human tissues led him to conclude that dietary fat, especially egg yolk, milk, and pork fat intake in adulthood contributed to atherosclerosis. Leary’s past work on rheumatic endocarditis had impressed Ludvig Hektoen (1863-1951), the well-reputed Chicago pathologist and a kindred spirit. Leary’s eleventh Hektoen lecture asserted that atherosclerosis was “a metabolic disease.”23 He urged “prevention” through avoidance of certain dietary fats. Such advocacy was an early example of today’s common refrain. Nutrition and healthy diet are structural elements of the social determinants of health. Leary’s contributions during this period (1930-1945) spanned both medical and social underpinnings of health by its emphasis on both animal models and ill-constructed dietary factors.

Relevance to current times

The “crisis atmosphere of the pandemic” in 1918 generated the Pittsburgh vaccine in “one week” for distribution. Such urgency did not extinguish the coexisting opposition to vaccines and masking. A variety of vaccines were manufactured. These circumstances are reminiscent of our current pandemic with its “warp speed” multi-sourced vaccine production, and a resistance to vaccine acceptance and mask donning. Convalescent plasma use also was prevalent then, as it is now during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, although details differ, many core principles and practices, both safe and unsafe, are alike. Current realization about the social causes of illness and wellness was also a precept well-known a century ago. Leary’s contemporaries, Alice Hamilton (1869-1970) and Richard Cabot (1868-1939), reached beyond blaming immediately apparent causes of illness to inapparent social structures and inequalities as the “causes of causes” for ill health.24–26 Nowadays we aspire to find a sage balance between providing individualized medicine and improving socially rooted imbalances. Leary’s research also recognized both the distal dietary origins and a proximal occlusive precipitating event for myocardial ischemia.

Were the Learys related?

This brings us to the connection between the erudite elder Leary and the younger, better-known psychedelic sixties Leary. They shared a name, but the fundaments of their reputations diverged widely. The most credible available evidence tells us that our Leary, not widely recognized now, was the great uncle of the hallucinogen-loving, publicity-seeking younger namesake.27 He was a different trendsetter deserving of our gratitude for his scientific enthusiasm and uncontroversial contributions.

References:

- Minutaglio B, Davis SL. The Most Dangerous Man in America: Timothy Leary, Richard Nixon and the Hunt for the Fugitive King of LSD. Twelve, New York; 2018.

- Timothy Leary. New England Journal of Medicine. 1954;251(27):1115-1116. doi:10.1056/NEJM195412302512715

- Gonzalez SH. The Cowpox Controversy: Memory and the Politics of Public Health in Cuba. Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 2018;92(1):110-140. doi:10.1353/bhm.2018.0005

- Copgrove J. “Science in a Democracy”: The Contested Status of Vaccination in the Progressive Era and the 1920s. Isis. 2005;96(2):167-191. doi:10.1086/431531

- A NEW ANTITOXIN.: One Discovered at Tufts Checks Pneumonia, Blood Poisoning, and Typhoid. – ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times – ProQuest. New York Times. Published February 12, 1909. Accessed December 19, 2020. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.sfpl.org/hnpnewyorktimes/docview/96927994/E82697C6332C40C2PQ/1?accountid=35117

- PALMER JF. A CRITICISM OF” FACTS AGAINST VACCINATION”. The Public Health Journal. 1913;4(9):506-508.

- Eyler JM. The State of Science, Microbiology, and Vaccines Circa 1918. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(3_suppl):27-36. doi:10.1177/00333549101250S306

- Leary T. THE USE OF INFLUENZA VACCINE IN THE PRESENT EPIDEMIC. Am J Public Health (N Y). 1918;8(10):754-768.

- BOSTON EPIDEMIC WANES.: Adjacent Industrial Cities, However, Report Grip Spreading. New York Times. October 4, 1918:24.

- SF Chronicle 29 Oct 1918. 20,000 DOSES OF SERUM ARE BROUGHT HERE: Representative of Boston Mayor Arrives in S. F. to Fight Epidemic NEEDS TO BE SUPPLIED City Complimented for Work Accomplished in War on Influenza Germ – ProQuest Historical Newspapers: San Francisco Chronicle – ProQuest. Published October 29, 1918. Accessed December 28, 2020. https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lapl.org/hnpsfchronicle/docview/576726386/fulltextPDF/54F63D8B68EC4EB1PQ/1?accountid=6749

- Stanley LL. Influenza at San Quentin Prison, California. Public Health Reports (1896-1970). 1919;34(19):996-1008. doi:10.2307/4575142

- Barnes HL. THE PROPHYLACTIC VALUE OF LEARY’S VACCINE. JAMA. 1918;71(23):1899-1899. doi:10.1001/jama.1918.02600490031009

- University of Pittsburgh. School of Medicine author. Studies on Epidemic Influenza : Comprising Clinical and Laboratory Investigations.; 1919. Accessed December 24, 2020. http://archive.org/details/35010560R.nlm.nih.gov

- Schwartz JL. The Spanish Flu, Epidemics, and the Turn to Biomedical Responses. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(11):1455-1458. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2018.304581

- Chien Y-W, Klugman KP, Morens DM. Efficacy of Whole-Cell Killed Bacterial Vaccines in Preventing Pneumonia and Death during the 1918 Influenza Pandemic. J Infect Dis. 2010;202(11):1639-16438. doi:10.1086/657144

- Smith AM, Huber VC. The Unexpected Impact of Vaccines on Secondary Bacterial Infections Following Influenza. Viral Immunology. 2017;31(2):159-173. doi:10.1089/vim.2017.0138

- Luke TC, Kilbane EM, Jackson JL, Hoffman SL. Meta-Analysis: Convalescent Blood Products for Spanish Influenza Pneumonia: A Future H5N1 Treatment? Annals of Internal Medicine. 2006;145(8):599-609. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-145-8-200610170-00139

- Gas in Deadly Fire Traced: Investigators of Boston Disaster Call Painter Who Decorated Club. Los Angeles Times (1923-1995). December 4, 1942:16.

- Cincy Catcher Hershberger Kills Self: Ex-Star Player Suicide Victim Red Receiver Becomes Despondent After Team Loses Twin Bill Hershberger, Red Catcher, Kills Himself. Los Angeles Times (1923-1995). August 4, 1940:A9.

- Satya-Murti S, Gutierrez J. Addressing the Social Determinants of Health: A Los Angeles Community Center’s Narrative from 1915 to 1925. Southern California Quarterly. 2019;101(4).

- O’Mahony S. After the golden age: what is medicine for? The Lancet; London. 2019;393(10183):1798-1799. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30901-8

- Leary T. Arteriosclerosis. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 1941;17(12):887.

- Leary T. ATHEROSCLEROSIS, THE IMPORTANT FORM OF ARTERIOSCLEROSIS, A METABOLIC DISEASE: ELEVENTH LUDVIG HEKTOEN LECTURE OF THE FRANK BILLINGS FOUNDATION OF THE INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE OF CHICAGO. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1935;105(7):475-481.

- Jacobson A. Alice Hamilton: physician and scientist of the dangerous trades – Hektoen International. Published Winter 2019. Accessed January 9, 2021. https://hekint.org/2019/03/08/alice-hamilton-physician-and-scientist-of-the-dangerous-trades/?highlight=alice%20hamilton

- Cabot RC. Social Work; Essays on the Meeting-Groung of Doctor and Social Worker. Boston and New York; 1919. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015028059452

- Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 2014;129(Suppl 2):19-31.

- Kamiya G. Devastating outbreak of flu starting in 1918 – San Francisco Chronicle (CA) – September 12, 2015 – page C1. San Francisco Chronicle. Published online September 12, 2015:3.

Acknowledgments: I extend my gratitude to Pamela S.M. Hopkins, Public Services and Outreach Archivist at Tisch Library, for facilitating access to images 1 and 3.

SATY SATYA-MURTI, MD., FAAN, is a clinical neurologist and health policy consultant on a limited basis. Following retirement, Saty has spent time researching cognitive biases, the social underpinnings of clinical medicine, Progressive Era medicine, forensic sciences, grandparenting, solar cooking, and volunteering.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Winter 2021 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply