Lea C. Dacy

Eelco F.M. Wijdicks

Rochester, Minnesota, United States

In a previous article, we reviewed the plausibility of opera deaths in wasting diseases such as that of Violetta in La Traviata. But operatic death is not always gentle: murder, suicide, and executions regularly befall operatic heroes and villains. These often make a great impression but do not necessarily make sense. In operas based on mythology or fairy tales, there is no need to explain anything, so that the protagonists of the Ring Cycle may die whenever Wagner decided they must. But works based (albeit loosely) on history or semi-realistic novels or plays must bear some semblance to reality or they become parodies. While willing to suspend belief in exchange for an uplifting musical experience, audiences remain bemused by deaths unrealistically extended by a farewell aria, rigor mortis with an immediate onset, and other farfetched scenarios.

To avoid such implausibility some composers have executions and murders occur offstage. In Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana Turidu dies offstage and we hear only the gunshot and screams from the chorus. Giordano’s Andrea Chénier and Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmélites use execution by (offstage) guillotine, as do Donizetti’s Tudor operas, Anna Bolena and Maria Stuarda. (Trills and coloratura gymnastics are what motivate ticket sales; a beheading onstage would either offend or lend itself to unintended comedy.) In Il Trovatore, Manrico’s execution ordered by his brother Di Luna also occurs offstage but does not lessen the sudden and shocking revelation that Di Luna unknowingly committed fratricide. In Tosca, Cavaradossi dies immediately by firing squad; in a quirky twist, he believes it is a mock execution in which he has only to pretend to die (second-nature for an operatic tenor) while his lover applauds his realistic acting, and then Tosca herself leaps to certain death from a parapet of Castel Sant’Angelo. Lenski in Eugene Onegin dies in a duel; Tchaikovsky prudently places his lengthy farewell aria before the exchange of gunfire. (Alexander Pushkin, who created the novel in verse on which Tchaikovsky’s opera is based, also was killed in a duel. Unlike Lenski, he lingered for several days and reportedly experienced a period of terminal lucidity similar to La Traviata‘s Violetta.1,2) The mezzo-soprano in the title role of Carmen, after having sung for most of the three previous acts as well as a lengthy, fractious duet with the tenor just before her fatal wound, is allowed to die immediately after being stabbed. These deaths, exquisite to the ears and harrowing to the eyes, still seem logical. But then there are others . . .

We expect a composer to concentrate on music, leaving details of plot progression and plausibility to the librettist. However, Giuseppe Verdi was spectacularly let down by a librettist. Based on an outline by Egyptologist Mariette Bey, who insisted that the plot was based on true events, the action occurs “sometime between 3,000 and 1,000 BC.” While critics praised Verdi for his music, they jeered at the thin plot and particularly at Aïda’s improbable death.3 Learning that her lover Ràdames has been condemned to death by suffocation in an underground tomb, Aïda conceals herself in the tomb to share his fate and intriguingly manages to die at the end of their final duet. Verdi himself, who wrote the first draft of the libretto, tried to make her death seem more logical. Verdi’s original draft had Aïda recite these lines: “My heart knew your sentence. For three days I have waited here.” Certainly, this would make her death from oxygen deprivation scarcely ten minutes after Ràdames enters the tomb more believable. However, Italian journalist Antonio Ghislanzoni, who finalized the libretto, cut these lines and left audiences, at least those not transported by the glorious strains of O terra addio, shaking their heads.3

Poison often appears as a means of murder or suicide, but the mechanism of action of these agents is based more on demands of the plot than on the properties of any toxic chemical. The title character of Simon Boccanegra receives a poisoned glass of water near the beginning of Act II but does not drink it until the end of the act, several arias and ensembles later, after surviving an assassination attempt with a knife. In Act III, at least several days have passed until Simon finally succumbs before the curtain falls. Verdi’s other two operas featuring poison, Il Trovatore and Luisa Miller, use faster-acting solutions so that the heroines can drink and die in the same act. However, the most implausible poison is the one death that appears in Cilea’s Adriana Lecouvreur, where only the title character succumbs to a bouquet of poisoned violets sent by her nemesis; her lover and her best friend are also exposed but remain apparently unaffected.

Stabbing can cause immediate death, as in Carmen. Scarpia in Puccini’s Tosca only lingers long enough to hurl some curses. Here the post-mortem event, rather than the death itself, defies physiology when the deceased goes immediately into rigor mortis. Before the stabbing, Tosca persuades Scarpia to provide a safe-conduct for her and her lover to leave Rome. He clutches this document in his hand as he dies. Directors typically have Tosca struggle to free it from his grasp; in reality, his hand should still be flaccid. However, some stabbed heroes have plenty of time to sum up their lives or issue a warning in song. Rodrigo in Don Carlo manages to sing while grimacing in pain between verses. Riccardo in Un Ballo in Maschera squeezes out a high C and even scrambles to his feet after a knife is plunged in his abdomen or chest (depending on the production).

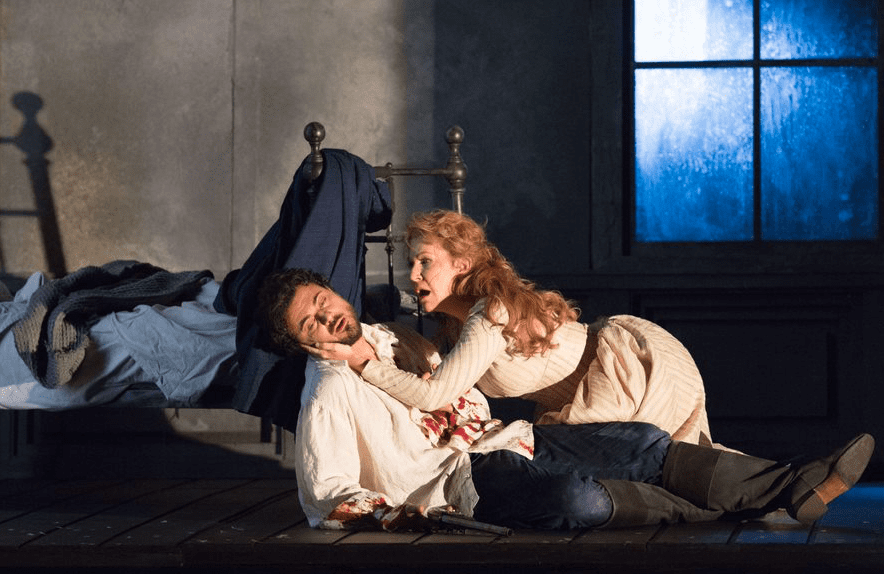

In contrast to suicide in real life, where loved ones are often left to wonder why, the operatic characters planning suicide often explain their motivation in great detail.4 Puccini’s heroines, Madame Butterfly and Tosca, commit suicide because they feel they have no other option:5 the geisha has lost her honor and the diva faces arrest for murder. Similarly, Massenet’s Werther (and the 1774 Goethe novella on which it was based) exemplify the romantic concept of self-destruction as inevitable. However, its operatic treatment is also highly improbable. Werther’s self-inflicted gunshot to the abdomen causes copious amounts of arterial blood to splat against the wall (Figure). In reality, death would quickly follow such profuse blood loss, but Werther manages to hang on until his beloved Charlotte arrives. He goes in and out of consciousness while singing. Some directors have him move around, assisted by (and bleeding copiously on) Charlotte—from bed to floor and back again, exertions that would normally hasten a bleed-out death.

Operatic deaths are often unduly protracted given the injuries and their normal progression in real life. Filmed opera, such as the Metropolitan’s Live in HD series, must capture two audiences, the one present in real-time in the house during filming and the audiences watching live in a cinema. Some of the latter may have never seen an opera in its original setting of the opera house, but most have seen death depicted in R-rated films, where fake blood and moulage are standard. And certainly these devices are helpful to the novice, struggling to understand a plot in Italian or Russian with often-unreliable subtitles. However, if Werther’s blood does not splat dramatically against the wall, the first audience, in an immense performance space, will miss it. Likewise, singers must exaggerate their movements, even if the nature of their “injury” is such that they would not be able to move at all in the real world, much less sing in their upper register.

Some singers grasp the entry wound with a loud cry and a grimace, only softening or returning during progress into the aria. Many fall down limp or move their head suddenly sideways as an unrealistic death-defining moment. Breath control is unimpaired and even optimized for the high notes. Trauma physicians know that stab or bullet wounds to the chest cause immediate lung collapse and may hit the heart, causing bleed-out very quickly. Further, wounds to the abdomen may eviscerate the gut, lacerate large arteries or the liver and spleen with rapid loss of blood and excruciating pain before the victim lapses into unconsciousness. Medically, there is no time for a final, heart-wrenching aria. There is often no time (or clarity of mind) to call for help. Fortunately, real-life patients arriving in the emergency department compos mentis often have a chance to survive with the right surgeon at hand. In opera, there will always be a tradeoff of reality and lyricism. Deaths, including violent ones, are a necessity in opera and are enjoyable even when implausible, thanks to the singers and orchestra.

References

- Macleod AD. Lightening up before death. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(4):513-516.

- Lim CY, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Terminal lucidity in the teaching hospital setting. Death Stud. 2020;44(5):285-291.

- Simon H. A Treasury of Grand Opera. New York Simon & Schuster; 1946.

- Feggetter G. Suicide in opera. Br J Psychiatry. 1980;136:552-557.

- Stack S. Opera subculture and suicide for honor. Death Stud. 2002;26(5):431-437.

LEA DACY, AB, is an Administrative Assistant in the Mayo Clinic Department of Neurology, a freelance musician, and a lifelong opera devotee.

EELCO WIJDICKS, MD, PhD, is a Professor of Neurology and History of Medicine at Mayo Clinic with subspecialty interest in Neurointensive Care and the author of Cinema MD: A History of Medicine on Screen (Oxford University Press 2020). Thanks to the not-so-subtle encouragement of his wife Barbara and his secretary (Lea Dacy), he has recently become an opera aficionado.

Leave a Reply