Lea C. Dacy

Eelco F. M. Wijdicks

Rochester, Minnesota, United States

I know she had tuberculosis! She was coughing her brains out . . . but still she kept right on singing.*

Operatic death is often glorious, melodious, and heartbreaking. Naturally, composers and librettists can claim pristine ignorance when it comes to the process of dying. Leaving aside violent, premeditated death, terminal illness is a favored device to drive an opera plot to its inevitable, tragic end. The chosen diseases reflect the era in which the libretto was written, but often a terminal illness is only implied. Operagoers may wonder at times—what caused this death and why is it so prolonged? Moreover, is it plausible?

Opera singers must act, and this includes dying. Dying often is the apotheosis of the last aria. Singers sink, lifeless, and the curtain falls. None of this acting approaches reality. Indeed, reality is not expected because 1) it would require an opera singer to watch a dying person for inspiration, 2) it would distract from the iconic music, and 3) most opera singers can carry off their incredible demises with panache. Which diseases have entered the art form of opera?

Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis predominates in opera (as in literature). Tuberculosis has been around since ancient Egypt but became endemic after 1900 with industrialization. Until science established its infectious cause, tuberculosis, or consumption, carried a certain cachet. The artistically talented seemed to be predisposed to it; Chopin, Grieg, Carl Maria von Weber, and Paganini all were consumptives. The clinical symptoms (pale skin, intermittent flushing, slenderness, and a “febrile sexuality”) inspired the creation of pathos-inducing but still alluring operatic heroines.1 Toulouse-Lautrec’s famous 1887 painting of A Young Woman At A Table, Poudre de Riz exemplifies the “fashionable consumptive pallor.”2 But tuberculosis could be fulminant (“galloping consumption”) and quickly fatal. Advanced disease affected the larynx,3 making it impossible to sing—let alone reach a high B or C.

Operatic heroines were particularly vulnerable. La Traviata‘s Violetta is a fragile courtesan with a generous spirit. Verdi based her on Marie Duplessis, a courtesan in 1840s Paris, beloved of both Alexandre Dumas fils and Liszt.4 Reunited in the final moments with her beloved Alfredo, Violetta joins him in a tender yet passionate duet that drains her remaining strength until even Alfredo (tenors in opera are astoundingly obtuse) notices she is close to death. The score lingers and halts, perhaps suggesting breathlessness. But then, briefly, she experiences an absence of pain and feeling of wellness. “Oh joy,” she delivers on a high B before collapsing and dying in an unusual trajectory. The librettist may have implied the “unrealistically sanguine,” “euphoric” state also known as spes phthisica, often observed in patients with advanced disease.2 Verdi’s music swells at this moment to enhance the experience. Terminal lucidity, the illusion of well-being shortly before death, had credibility among physicians of the Victorian era5 but appears infrequently in contemporary literature, although MacLeod notes that sedation could mask it. In a retrospective study at a teaching hospital, Lim et al. examined levels of consciousness among 338 dying patients admitted over a one-year period, six of whom met their criteria for terminal lucidity.6 However, the lucid episodes witnessed all preceded coma, with death apparently occurring with a final breath rather than a high B.

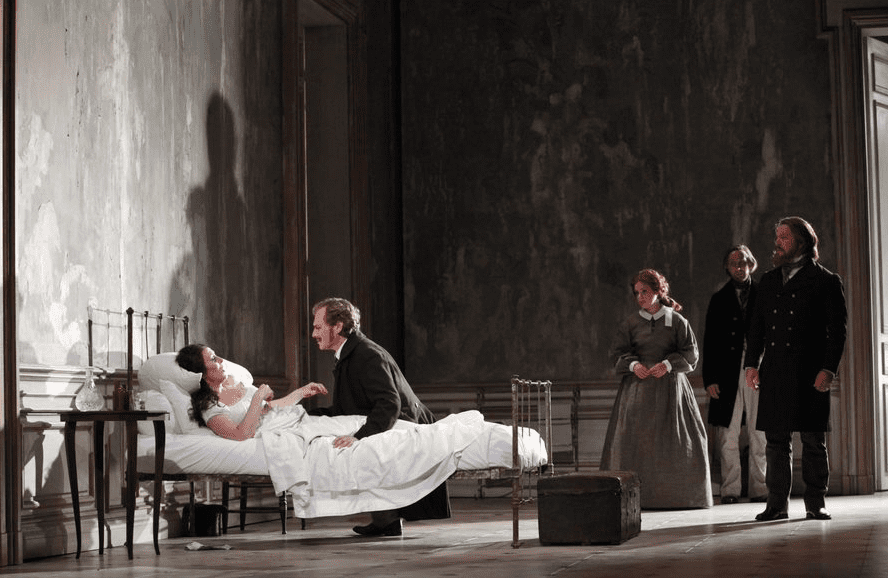

Sometimes an effort to inject subtlety or realism in opera infuriates the critics. Sir Jonathan Miller, a director of opera and theater (and a non-practicing physician), got panned for making Violetta’s death too medically realistic. He had her remain in bed during the whole final act under the plausible assumption that she would be too weak to get up.7 The critic, however, did not like being deprived of that triumphant leap with which sopranos traditionally deliver the final notes because it did not follow Verdi tempo change. Nonetheless, the implication that a real depiction of the dying process might not be dramatic enough is analogous to the choices film directors felt they needed to make as evidenced by many horrific death scenes in the setting of terminal illness.8

Like Violetta, Mimì of La Bohème was a courtesan with consumptive allure and also was based on an actual person, the sometime mistress of writer Henri Murger (immortalized as the opera’s Rodolfo), whose autobiographical novel, Scènes de la vie Bohème (1848), provided source material for the Giacosa/Illica’s libretto set to Puccini’s score.9 In Act I, she complains of breathlessness from climbing stairs. In Act III, her illness has progressed with increased fatigue and coughing. Several writers speculate that Rodolfo breaks off with Mimì in Act III because he fears catching the disease from her.1,10,11 While Puccini and his librettists surely would have known of Robert Koch’s 1882 identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Murger/Rodolfo, writing in the 1840s, would not, and Puccini et al. commit no literary anachronism. Indeed, nothing in the libretto supports this idea. Rodolfo’s true motivation for the break-up is his fear that his drafty, squalid garret will exacerbate Mimì’s illness. After returning to the artists’ garret to die, Mimì’s final sung notes fade away, creating more a realistic demise than Violetta’s. Her obtuse lover Rodolfo (a tenor, of course), assumes she is dozing peacefully until his friends tells him she is dead and he cries out “Mimì. Mimì,” falling over her body in total despair—curtains fall.

Other tragic opera heroines exhibit symptoms of consumption. Prévost’s 1731 novel Les aventures du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut inspired operas by both Massenet and Puccini. The privations, including internment, a cross-continental voyage in steerage (the Puccini version), and malnutrition preceding Manon’s death in the final act of each certainly were conducive to the development of tuberculosis. Mason also credits it with Antonia’s death in Act III of Les Contes d’Hoffman based on her pale cheeks, flushing, cough, and chest weakness.11

Sudden swoons into eternity

As the final act of Faust begins, Marguerite awaits execution for infanticide. In yet another “clueless-tenor” example, Faust, who has already sold his soul to the devil (who has accompanied him to the prison cell), naively believes he can rescue her. We, of course, know that Mephistopheles plans to gain Marguerite’s soul as well as Faust’s, but after rejecting Faust and launching fervent appeals to Christ, Mary, and all the saints, Marguerite falls lifeless and her soul ascends to Heaven, thus depriving both the hangman and the devil. Presumably, the Almighty can do as He pleases, but what about the numerous other operas where characters keel over for no plausible reason (without divine intervention)? Wagner used this extensively (e.g., Isolde, Elsa, Kundry). Some authors have posited a cardiac condition. Acute death (swooning is a better description) has been attributed to cardiac arrhythmias in congenitally abnormal hearts such as mitral valve prolapse unable to handle a stressful event.12 Cardiac arrhythmias cause a sudden faint and collapse and, to some extent, that is what opera singers can do. However, in dramatic operas with a sudden, non-violent heroine’s death, “heartbreak” is a common trigger. Physicians have diagnosed the so-called “broken heart syndrome” (stress cardiomyopathy) for years—mostly in middle-aged women (unlike tragic, usually young operatic heroines) after an unexpected, overwhelmingly stressful event. It causes cardiac shock and may even lead to an intensive care admission.13,14 Perhaps all the swooning and near syncope we see is a reflection of this physiologic state. Unlike Mason, Dauber attributes Antonia’s death in Les Contes d’Hoffman to this syndrome.12

Conclusion

Operatic deaths are often protracted, perhaps unduly so given the nature of the malady. In defiance of physiology and in physical pain, some operatic characters sing longer and more forcefully than any palliative care physician has ever witnessed. Operas based on mythology or fairy tales avoid these pitfalls of plausibility. However, the works based (albeit loosely) on history or semi-realistic novels or plays must bear some semblance to reality or become parodies of themselves. Directors seeking to make a work more relevant by moving it to a modern-day setting may inadvertently create additional plausibility issues, such as explaining away or providing a current substitute for Mimì’s or Violetta’s tuberculosis, a disease largely eradicated in the twentieth century.

A quiet death may occur in opera, which would reflect reality, but it is rare. Breath control is not impaired; in fact, it is optimized to create the high notes. Opera physicians often arrive too late (La Bohème). Inevitably, they are never helpful. “Monsieur Javelinot,” begs the prioress, Mme. De Croissy, in Dialogues des Carmélites, “I beg you to give me more of that medicine, just one more dose.” The physician refuses and lets her delirium go on untreated: “I’m afraid Your Reverence cannot take another dose.” Dr. Grenvil is similarly unhelpful in La Traviata. He tells Violetta she will recover but then, in an aside, tells her maid that the end is imminent.15 The worldly Violetta is undeceived: “Oh, the little white lie is permissible in a doctor.”

Filmed opera (most notably, the Metropolitan’s Live in HD series) is a new phenomenon, but audiences in a cinema should never forget that they are watching a filmed performance originally intended for a major (i.e., large) opera house. Filming places new demands on singers (better acting). Still, the singers must exaggerate movements because a nuanced performance is lost in the upper balconies, where some of the most loyal opera patrons typically sit. And opera audiences are good-natured when it comes to stretching reality. Where else could a heroine with impaired respiratory and pharyngeal function sprint across the stage to let go with that high B?

End note

* Cher as Loretta Castorini in Moonstruck (MGM/UA Communications, 1987) after watching a performance of La Bohème.

References

- Morse MM. Through the opera glass: a critical analysis of tuberculosis as presented in opera. Pharos Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Med Soc. 1998;61(4):11-14.

- Snowden FM. Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 2019.

- Bynum H. Spitting Blood: The history of tuberculosis 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012.

- Simon H. A Treasury of Grand Opera. New York Simon & Schuster; 1946.

- Macleod AD. Lightening up before death. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7(4):513-516.

- Lim CY, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Terminal lucidity in the teaching hospital setting. Death Stud. 2020;44(5):285-291.

- Madison WV. Glimmerglass 2009: La Traviata. In: Madison WV, Madison L, eds. BILLEVESÉES. Vol 2020. Paris2009.

- Wijdicks EFM. Cinema, M.D. New York: Oxford University Press; 2020.

- Simon H. 100 Great Operas and Their Stories: Act-by-act Synopses. Third ed. New York Random House; 1989.

- Hutcheon L, Hutcheon M. Opera: Desire, Disease, Death. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1996.

- Mason RB. Seeing medicine through opera glasses. CMAJ. 1996;154(6):921-923.

- Dauber LG. Death in opera: a case study, “Tales of Hoffman”–Antonia. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(7):838-840.

- Bybee KA, Prasad A. Stress-related cardiomyopathy syndromes. Circulation. 2008;118(4):397-409.

- Samuels MA. The brain-heart connection. Circulation. 2007;116(1):77-84.

- Willich SN. Physicians in opera–reflection of medical history and public perception. BMJ. 2006;333(7582):1333-1335.

LEA DACY, AB, is an Administrative Assistant in the Mayo Clinic Department of Neurology, a freelance musician, and a lifelong opera devotee.

EELCO WIJDICKS, MD, PhD, is a Professor of Neurology and History of Medicine at Mayo Clinic with subspecialty interest in Neurointensive Care and the author of Cinema MD: A History of Medicine on Screen (Oxford University Press 2020). Thanks to the not-so-subtle encouragement of his wife Barbara and his secretary (Lea Dacy), he has recently become an opera aficionado.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 2 – Spring 2021

Leave a Reply