Adil Menon

Cleveland, Ohio, United States

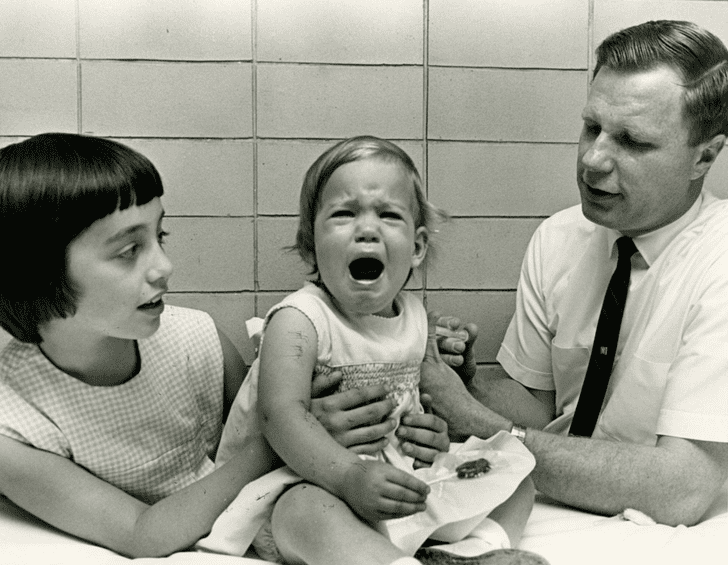

Working my way through a biography of pioneering vaccine developer Maurice Hilleman titled Vaccinated, I was struck by how often the researchers of his era, such as Jonas Salk, tested their vaccines both on their own children as well as on children with cognitive challenges. If indeed the latter were taken advantage of because they were unable to give consent, then why did the researchers likewise risk their own children? Hilleman argues that if all babies were to be vaccinated against mumps without their explicit informed consent, why should mentally challenged children not also be protected. Clearly, the guidelines promulgated for the protection of vulnerable subjects in research can inadvertently be detrimental or exclusionary to those they are designed to protect.1

Somewhat counter-intuitively, the current informed consent process put in place to safeguard subjects may also engender disparities. In obtaining informed consent for research on children, not only must the entire family be involved but consent from the child is also sought. For subjects age six to seven a simple oral description of the child’s involvement is given to the participant and verbal assent is requested. For those above thirteen written assents are requested from both parent and child, using age-appropriate and background-appropriate documents. Effort is made within the study design to ensure that pediatric trial participants understand their situation, with a focus on appropriate age and educational background not always considered in adults. In some cases, however, the informed consent process designed to reassure and convince patients of the value and safety of research may be confusing and frighten them away instead.2,3

Rigorous exclusion criteria, purportedly written to improve safety, may further compound the issue. For example, African Americans have higher incidences of co-morbid conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease, and may therefore be excluded from clinical trials.4,5 Furthermore, research by Dr. Michelle Van Ryn of the Mayo Clinic, shows how real risks of comorbidity and treatment interactions intertwine with a clear pro-white bias on the part of physicians. Healthcare providers in the study rated Caucasians as having a lower risk for substance abuse, and higher rates of compliance to treatment, even when controlling for an extended set of covariates. At the same time, African Americans were perceived as less likely to desire an active lifestyle, participate in prescribed rehabilitation, and as having a greater risk of low social support. Physicians in this study also rated African Americans as less intelligent and educated than their white counterparts. Controlling once again for socioeconomic status (SES), and accounting for patients’ self-reported years of education, physicians rated African Americans “very” intelligent half as often as they did whites and were less than 2/3 as likely to view them as “very” or “somewhat” educated.6,7 A constellation of exclusion criteria means that even if African Americans are willing to participate in research, they are often barred from doing so, which lends credence to the idea that perhaps protocols and researchers have become so skilled at excluding vulnerable populations that the system has become overzealous.

End Notes

- Paul A. Offit, Vaccinated: One Man’s Quest to Defeat the World’s Deadliest Diseases. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 2008.

- Aviva, Katz, and Sally Webb. “Informed Consent in Decision-Making in Pediatric Practice.” Pediatrics 138, no. 2 (August 25, 2016). Accessed December 23, 2020. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1484.

- “Process for Handling Referrals to FDA Under 21 CFR 50.54 – Additional Safeguards for Children in Clinical Investigations.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration. December 2006. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/process-handling-referrals-fda-under-21-cfr-5054-additional-safeguards-children-clinical.

- Michelle Van Ryn, and Jane Burke. “The Effect of Patient Race and Socio-economic Status on Physicians Perceptions of Patients.” Social Science & Medicine 50, no. 6 (2000): 813-28. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x.

- Ivy W. Maina, Tanisha D. Belton, Sara Ginzberg, Ajit Singh, and Tiffani J. Johnson. “A Decade of Studying Implicit Racial/ethnic Bias in Healthcare Providers Using the Implicit Association Test.” Social Science & Medicine 199 (February 2018): 219-29. Accessed December 23, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009.

- Michelle Van Ryn, and Jane Burke. “The Effect of Patient Race and Socio-economic Status on Physicians Perceptions of Patients.” Social Science & Medicine 50, no. 6 (2000): 813-28. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x.

- Ivy W. Maina, Tanisha D. Belton, Sara Ginzberg, Ajit Singh, and Tiffani J. Johnson. “A Decade of Studying Implicit Racial/ethnic Bias in Healthcare Providers Using the Implicit Association Test.” Social Science & Medicine 199 (February 2018): 219-29. Accessed December 23, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009.

Bibliography

- Katz, Aviva, and Sally Webb. “Informed Consent in Decision-Making in Pediatric Practice.” Pediatrics 138, no. 2 (August 25, 2016). Accessed December 23, 2020. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1484.

- Maina, Ivy W., Tanisha D. Belton, Sara Ginzberg, Ajit Singh, and Tiffani J. Johnson. “A Decade of Studying Implicit Racial/ethnic Bias in Healthcare Providers Using the Implicit Association Test.” Social Science & Medicine 199 (February 2018): 219-29. Accessed December 23, 2020. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009.

- Offit, Paul A. Vaccinated: One Man’s Quest to Defeat the World’s Deadliest Diseases. New York, NY: Harper Perennial, 2008.

- “Process for Handling Referrals to FDA Under 21 CFR 50.54 – Additional Safeguards for Children in Clinical Investigations.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration. December 2006. Accessed December 23, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/process-handling-referrals-fda-under-21-cfr-5054-additional-safeguards-children-clinical.

- Ryn, Michelle Van, and Jane Burke. “The Effect of Patient Race and Socio-economic Status on Physicians Perceptions of Patients.” Social Science & Medicine 50, no. 6 (2000): 813-28. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00338-x.

ADIL MENON is a fourth-year medical student at Case Western Reserve School of Medicine. Before medical school, he earned honors in the History of Science and Medicine at the University of Chicago and received his master’s degree in bioethics from Harvard Medical School. His written work may be found in journals including Hektoen International, the Harvard Medical School Bioethics Journal, The Pathologist, and JAMA Cardiology, with additional work found on Student Doctor Network and the Merck Manuals Med Student Stories. His professional interests include microbiology, hematopathology, medical education, and global health equity and infrastructure.

Leave a Reply