The Luggnaggians are a polite and generous people . . . they show themselves courteous to strangers.

One day . . . I was asked by a person of quality, “whether I had seen any of their struldbrugs, or immortals?” . . . He told me “that sometimes, though very rarely, a child happened to be born in a family, with a red circular spot in the forehead, directly over the left eyebrow, which was an infallible mark that it should never die.” . . .

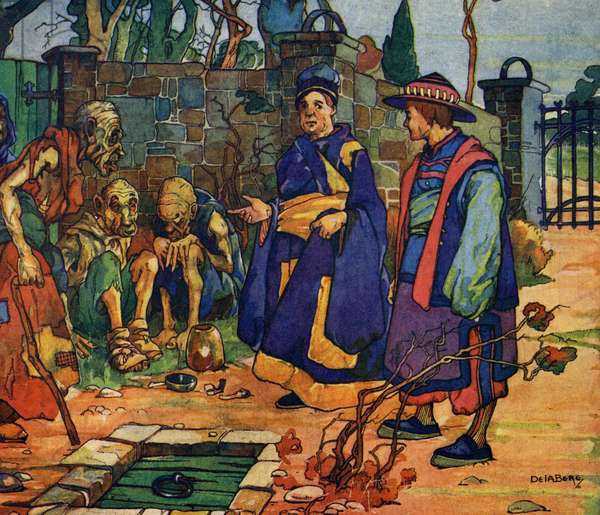

After this preface, he gave me a particular account of the struldbrugs among them. He said, “they commonly acted like mortals till about thirty years old; after which, by degrees, they grew melancholy and dejected. . . . When they came to fourscore years, which is reckoned the extremity of living in this country, they had not only all the follies and infirmities of other old men, but many more which arose from the dreadful prospect of never dying. They were not only opinionative, peevish, covetous, morose, vain, talkative, but incapable of friendship, and dead to all natural affection. . . . Envy and impotent desires are their prevailing passions. But those objects against which their envy seems principally directed, are the vices of the younger sort and the deaths of the old. By reflecting on the former, they find themselves cut off from all possibility of pleasure; and whenever they see a funeral, they lament and repine that others have gone to a harbour of rest to which they themselves never can hope to arrive. They have no remembrance of anything but what they learned and observed in their youth and middle-age. . . . The least miserable among them appear to be those who turn to dotage, and entirely lose their memories. . . .

“As soon as they have completed the term of eighty years, they are looked on as dead in law; their heirs immediately succeed to their estates; only a small pittance is reserved for their support; and the poor ones are maintained at the public charge. After that period, they are held incapable of any employment of trust or profit; they cannot purchase lands, or take leases; neither are they allowed to be witnesses in any cause, either civil or criminal. . . .

“At ninety, they lose their teeth and hair; they have at that age no distinction of taste, but eat and drink whatever they can get, without relish or appetite. The diseases they were subject to still continue, without increasing or diminishing. In talking, they forget the common appellation of things, and the names of persons, even of those who are their nearest friends and relations. For the same reason, they never can amuse themselves with reading . . . and are deprived of the only entertainment whereof they might otherwise be capable.

“The language of this country being always upon the flux, the struldbrugs of one age do not understand those of another; neither are they able, after two hundred years, to hold any conversation . . . and thus they lie under the disadvantage of living like foreigners in their own country.” . . .

They were the most mortifying sight I ever beheld; and the women more horrible than the men. Besides the usual deformities in extreme old age, they acquired an additional ghastliness, in proportion to their number of years, which is not to be described. . . .

The reader will easily believe, that from what I had heard and seen, my keen appetite for perpetuity of life was much abated.

Abridged from Jonathan Swift (1667–1745): Gulliver’s Travels or Travels into several remote nations of the world, part 3, chapter 10.

Highlighted Vignette Volume 13, Issue 2 – Spring 2021 & Volume 15, Issue 1 – Winter 2023