Josephine Ensign

Seattle, Washington, United States

|

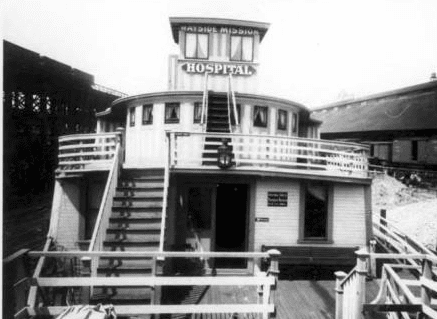

| Entrance to Wayside Mission Hospital housed on the steamboat IDAHO, Seattle, circa 1900. Photo: University of Washington Libraries, Special Collections UW6573. |

Short of stature and tall of tales, Alexander de Soto was by some accounts a highly educated, skilled, compassionate physician and surgeon, and by other accounts a charlatan, medical quack, faith healer, and quixotic dreamer. Born on July 24, 1840, in the Canary Islands to the Spaniard Alexander de Soto and American Elizabeth Crane, Dr. de Soto claimed to have been a descendent of the sixteenth-century Spanish explorer to America, Hernando de Soto. He told people that as a young man in Spain he had studied for the Jesuit priesthood, fell out with the Catholic Church, and completed his education at the University of Madrid.1

In 1862, de Soto moved to New York City where it does not appear that he tried to practice medicine of either the faith or conventional sort. Instead, he became a professional gambler and a morphine addict. He lived in rooming house tenements and police station homeless shelters. De Soto cured himself of his addictions in 1890 through the Holiness Movement at the Bowery Street Mission, one of the first such missions in the country.

De Soto was living and working at the Bowery Street Mission when he caught gold fever. He led a proselytizing expedition, setting out on foot from New York City to Seattle, hoping from there to take a boat to the gold fields in the Yukon. He planned to preach on the sins of greed and debauchery in Alaska. He called their group the Gospel Argonauts.2 Upon his arrival in Seattle, likely in early June 1898, de Soto sought out local newspaper reporters to cover his missionary work.

In a half-page article titled “De Soto’s Descendant and His Proposed Christian Work” in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer on Sunday, July 31, 1898, Irving Safford described de Soto as “a little blue-shirted man” with a “cultured Castilian accent.” De Soto had plans for a floating hospital he called Christ Hospital that he wanted to have built in Seattle, transported to Dawson City, and established there as a mission hospital. “The work, it needs me you know,” he is quoted as saying, with a parenthetical addition by Safford that “he himself is a physician”—as if it just occurred to de Soto that he could become a physician as well as a captain.

At that time throughout America many people could and did become physicians, not through formal, then termed “regular” medical school training, but through apprenticeship and by simply presenting themselves as physicians. Regulation and licensing of medical practitioners were rudimentary at best, even in older cities like New York. In Washington, which had only become a state in 1889, physician licensing was just beginning.3

De Soto decided to stay in this frontier city of Seattle. He moved into an abandoned barn in the Skid Road area at the mouth of the Duwamish River. The marshy area where Dr. de Soto and his homeless patients lived was called the Lava Beds for its numerous brothels and saloons. De Soto began a Robin Hood sort of medical practice. He charged high fees for medical consultations on rich people in their homes and then provided free medical care and food for the homeless and poor in Skid Road.

By February 1899, de Soto had moved to a rented basement in a tenement building in the heart of Skid Road. He turned the basement into the Wayside Mission, presumably named for its location along the waterfront as well as for the mission’s focus on health care and other services for people who had become society’s castoffs.

After a wealthy Seattle woman died under the care of de Soto, a group of Seattle physicians accused Dr. de Soto of being a faith healer, a Christian Scientist, and not a regular physician. They pointed out that he had no documented medical education and that he had not applied for a medical license in Washington State. De Soto claimed that these physicians were picking on him because he was successfully caring for Seattle’s “unfortunate souls” when they were not.

Dr. de Soto met wealthy Seattle philanthropists and a Seattle judge who supported his idea of opening a hospital mission on a boat along the Seattle waterfront. They formed the Seattle Benevolent Association, convinced city officials to rent space to their association at the City Dock, found and bought the decommissioned former opium-smuggling side-wheeler Idaho, and proceeded to convert the boat into a hospital. De Soto likely knew about and had seen the “fresh air” boats and floating hospitals for babies and for tuberculosis patients in New York City. The Wayside Mission Hospital in Seattle opened in early April 1900.

The June 1900 United States census for Seattle Precinct 1 in Skid Road records Alexander de Soto, physician, as head of “household” of the Wayside Mission Hospital, accompanied by forty-nine “lodgers.” Of the nine female lodgers, two are listed as nurses, including head nurse, Irene Byers. Dressmaker, servant, cook, and hairdresser are listed as professions for the other women. For the men, there are six “seamen” or sailors, lumbermen, carpenters, cooks, day laborers, a steamboat captain, a saloon keeper, and a druggist.

In a late October 1900 newspaper article, Dr. de Soto is described by his “soft, feminine, gentle hands.”4 The reporter adds that de Soto’s detractors accuse him of having an “oriental imagination,” emphasizing his exotic “otherness” and perhaps Moorish influence to the majority white Seattle population. But the reporter counters this with the doctor’s “systematic plan of applied Christianity,” which had attracted many supporters of his mission work to provide medical care to those in need but “not to harbor ‘hobos.’” He is described as a “practical mystic.”

Dr. de Soto received funding directly from the city of Seattle for the care of patients addicted to morphine, as well as care for indigent patients. At the time, Seattle and King County had an agreement that the city would care for “ill paupers” if they had been in Washington State for less than six months.5 In addition, the city agreed to take care of all emergency cases since King County Poor Farm and Hospital south of Seattle in Georgetown was too far removed from the city and was not equipped for emergency care.

A Seattle area newspaper, The Commonwealth, carried an article by Malcolm McDonald on May 23, 1903. Titled “The Samaritan Spirit—Seattle’s Pharisees,” McDonald reports that the city wants to develop the land and dock where the Wayside Mission Hospital is located. “It is the only hospital in the city ready at all times to receive the poor—the utterly poor who in sickness know no relief but death or the help of the Good Samaritan.” McDonald points to the high commercial value of land along the Seattle waterfront and asks, “Is any land too valuable for the saving of a human life? Is there no room in Seattle for an institution that has pity and not profit for the motive of its existence?”

In July 1904, Dr. de Soto was forced out of his work with the mission by the city and by members of the Benevolent Association because his management became unsatisfactory. The specific concerns are unclear. Whatever the reasons for Dr. de Soto being forced out of the medical mission he had dreamed of, started, and run for four years, the floating hospital, now called the Wayside Emergency Hospital, was turned over to Fanny W. Connor and Marion Baxter, social reformers. Under their leadership, the renamed Wayside Emergency Hospital continued to operate much as before onboard the Idaho along the Seattle waterfront.6

De Soto continued to work in Seattle as a physician. At age ninety-three he married Irene Byers, mother of his two children and a former nurse at the Wayside Mission Hospital. Three years later, he died of injuries sustained in a fall in Brooklyn, New York.7

In 1907, the Idaho became too leaky to repair and the Wayside Emergency Hospital was moved to the Sarah B. Yesler building. The Wayside Emergency Hospital continued to function until 1909 when Seattle opened its own clinic and hospital downtown along Yesler Way in the Public Safety Building. On the last day of March 1909, nineteen patients were moved from the Wayside Hospital to the new Seattle City Hospital.8

Dr. Alexander de Soto and his Seattle waterfront floating mission hospital are much more than just quirky side notes in the medical history and legacy of care for homeless people in Seattle. The Gospel Argonaut, the practical mystic, through his medical mission work, forced the citizens of Seattle to not only confront the reality of an increasing number of ill homeless people in their midst but also to find innovative solutions for their care.

This piece is excerpted from Skid Road: On the Frontier of Health and Homelessness in an American City, forthcoming from Johns Hopkins University Press.

Notes:

- Irving Safford, “De Soto’s Descendent and His Proposed Christian Work,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 31, 1898.

- “Klondiker’s Souls,” Evening Journal, November 9, 1897.

- Nancy Rockafellar and James W. Haviland, “The Broad Sweep: A Chronological Summary of the First 100 Years of Medicine and Dentistry in Washington State, 1889-1989,” in Saddlebags to Scanners: The First 100 Years of Medicine in Washington State, ed. Nancy Rockafellar and James W. Haviland (Seattle:Washington State Medical Association, Education and Research Foundation, 1989), 1-26.

- “Dr. De Soto and His Work,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 28, 1900.

- King County Washington Commissioners, Beginnings, Progress and Achievement in the Medical Work of King County, Washington (Seattle, WA: Peter’s Publishing, 1930).

- Katharine Major, “Nursing Seattle’s Unfortunate Sick,” American Journal of Nursing 6, no. 1 (1905):32-34.

- “Dr. De Soto, 96, Dies after Falling into Bay,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 12, 1936.

- King County Washington Commissioners, Beginnings, Progress and Achievement.

JOSEPHINE ENSIGN, DrPH, ARNP, is professor of nursing and adjunct professor in the School of Arts and Sciences, Department of Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies at the University of Washington in Seattle. She teaches public health, health policy, and health humanities. Ensign is the author of Catching Homelessness: A Nurse’s Story of Falling Through the Safety Net and Soul Stories: Voices from the Margins. She was a 2018 U.S.-U.K. Fulbright scholar, based in Edinburgh, for research on the history of English and Scottish Poor Laws. Her book, Skid Road: On the Frontier of Health and Homelessness in an American City is forthcoming (2021) from Johns Hopkins University Press.

Fall 2020 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply