JMS Pearce

East Yorks, UK

|

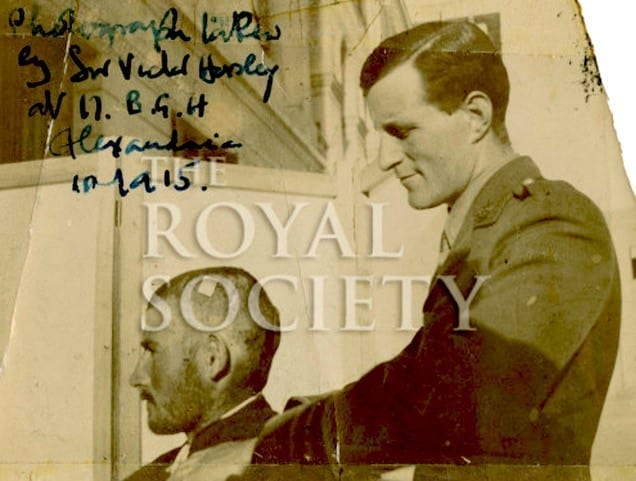

| Fig 1. Portrait of F.M.R. Walshe in profile wearing Royal Army Medical Corps uniform viewing a patient in Alexandria, Egypt. “Photograph taken by Sir Victor Horsley at 17. B.G.H. [British General Hospital] Alexandria in 1915.” Credit: © The Royal Society |

Francis Martin Rouse Walshe (1885-1973) (Fig 1) was a remarkable man, that rare mixture of clinician and student of basic science. He was always in pursuit of the mechanisms and physiology of nervous disease, always questioning received dogma, and always critical of sloppy thinking and writing. Born in London of Irish descent he was educated at Prior Park College, Bath, and read medicine at University College London, graduating in 1910. The teachings of Professors Bayliss and Starling impressed him and Sherrington’s recently published Integrative Action of the Nervous System (1906) excited his curiosity.1 Importantly, familiar figures of his youth were Sir William Gowers and Hughlings Jackson.

At University College Hospital he was house surgeon to Sir Victor Horsley. He trained at Queen Square as House Physician and Resident Medical Officer, obtaining the MD in 1912, MRCP in 1913, and FRCP in 1920. He was appointed Consulting Neurologist to the British Forces in the Middle East during World War I, was awarded the OBE in 1919, and was mentioned in dispatches. Returning to London, his flare and brilliance were rewarded when he was appointed Physician at Queen Square in 1921 and University College Hospital in 1924.

Walshe’s role was essentially as a clinician and incisive critic of theories of neurophysiology, especially their clinical relevance.2 Few controversies or doubtful speculations evaded his attention.

Early in his career he analyzed the physiology of human reflexes. From his studies of wartime spinal cord injuries he reported that the reflexes, including the Babinski phenomenon, were part of a “paraplegia in flexion” that originated in the cord and were independent of the cerebral cortex.3 He published weighty papers on neural physiology, mainly in Brain. He gave detailed accounts of the giant cells of Betz, the motor cortex, and the pyramidal tract.4 His long paper “On the anatomy and physiology of cutaneous sensibility”5 is a model of profound reasoned conclusions in which he rejected Head’s then widely accepted notions of epicritic and protopathic sensation.

|

| Fig 2. Walshe’s Diseases of the nervous system |

His later writings on the brain stem in relation to consciousness6 criticized the publications of Penfield and others; he rejected Penfield’s famed homunculus as pure jabberwocky. He became involved with controversies about the management of poliomyelitis and its spread. He appraised the prevalent movement disorders in encephalitis lethargica.7

These and many other lucid observations and exemplary, logical writings influenced the neurological community worldwide.8 Hughlings Jackson’s concepts clearly resound throughout his writings, yet he was immersed in contemporary investigations, but applied them only when he thought them clinically relevant.

. . . There can, I believe, be no doubt that for too many of us there is an occult virtue in experimentally obtained proof that clinical proof lacks. Yet, of course, this view is quite illogical.1

Walshe mastered a remarkable array of knowledge recorded in his Diseases of the nervous system (Fig 2), Critical Studies in Neurology, and Further Critical Studies in Neurology (Fig 3). They covered comparative anatomy, cytoarchitecture, and experimental physiology, in addition to clinical phenomenology. Yet the imprecise thinking of other authors to unsolved problems was often the butt of his acidulous critiques; for example on the origin of the pyramidal tract he concluded:

“Yet when all has been said about defects in technical method, there remain clear indications that the defects of the intellectual method have been equally responsible for the slow and wavering character of advance in our knowledge.”9

Following a dictum of Hughlings Jackson, Walshe pointed out in 194710 that to define the function of a brain region in terms of the symptoms following its damage is likely to result in a misidentification of the functions of that brain region. His example was a broken tooth on a gear in a car’s transmission, which results in such symptoms as a “thunk” heard once each revolution. The function of the tooth was not to prevent thunks, and the function of the peri-Sylvian regions is not to prevent aphasia, he said.

“Language cortex . . . Defining its function by what stops working in its absence confuses a correlation with a cause.”

|

| Fig 3. Walshe’s Critical Studies in Neurology and Further Critical Studies in Neurology. |

Honors abounded. He was made DSc in 1924 and delivered the Oliver Sharpey Lecture of the Royal College of Physicians. He edited Brain from 1937-1953. He became FRS in 1946 and delivered the Harveian oration of the Royal College of Physicians in 1948. He was President of the Association of British Neurologists in 1950-1951 and President of the Royal Society of Medicine, 1952-1954. He was awarded the Ferrier Lecture of the Royal Society entitled: The contribution of clinical observation to cerebral physiology. All these achievements and widespread recognition attest to his scholastic prowess—today still evident and stimulating in reading his works. At meetings, he was an outspoken critic of anything he considered tenuous or ill considered. I recall several occasions when his cutting wit humbled many an aspiring trainee or seasoned proponent of unproven conjectures. From 1953, he became increasingly absorbed in philosophical aspects of mind-brain relationships.11 Devoted to Queen Square, he described it as “Queen Square: The Cradle Of British Neurology.”12 His preeminent scientific and critical studies were rewarded by election to the Royal Society in 1946. He was knighted in 1953.

Some brief insights

His orientation remained essentially clinical; he once remarked:

“The more resources we have, and the more complex they are, the greater are the demands upon our clinical skill. These resources are calls upon judgment and not substitutes for it. Do not, therefore, scorn clinical examination; learn it sufficiently to get from it all it holds, and gain in it the confidence it merits.”

He was renowned and feared for his outspoken skepticism of woolly unscientific thinking, and uncritical use of language. Equally concerned with the literary qualities of hospital notes, he wrote in The Lancet, 1956:

“How rarely is the eye, as it traverses these deserts of nouns and of plus and minus signs, refreshed by some flash or originality of observation or presentation. I suggest that what would revive our clinical nosography is a return for refreshment to the clinical writings of forty or more years ago.”

He was likewise critical of fancy, portentous terminology, which he believed clouded the understanding of basic mechanisms.

Walshe the man

At times he appeared remote, difficult to know, for he did not encourage those who sought his affection or approbation. Even in old age he was strikingly handsome, elegantly dressed, and seemed to exude an unconscious authority, which is also inescapable in his writings. Critchley, who worked with him13 for fifty years noted:14

“For sheer intellectualism he towered above his colleagues, highly gifted individualists though they were . . .”

“There was no one like Walshe when it came to distinguishing hocus from pocus.”

“. . . His command of language was superb, but he did not allow persiflage to debase the seriousness of his work. He kept his quips and wisecracks for his conversation and letter-writing.”

His work itself perhaps conceals his underlying concern with the ailments of humanity, well illustrated in his Linacre lecture: Humanism, History and Natural Science in Medicine.15 Interestingly, he opposed the inception of the National Health Service, objecting not to free treatment for the needy, but to hospitals being funded by the government. He refused all financial payments for his own hospital practice throughout a long career. Charging remarkably modest fees, he managed all his affairs on his earnings in private practice. Into his ninth decade, he continued to write to friends and colleagues. He had few other hobbies.

He married Bertha Marie Dennehy in 1916 by whom he had two sons, one of whom, JM Walshe, pioneered the treatment of Wilson’s disease with penicillamine.

Walshe’s Books16

Diseases of the Nervous System. E & S Livingstone, Edinburgh & London, 1940, 11th edition 1970.

Critical Studies in Neurology. E & S Livingstone, Edinburgh & London, 1948.

Further Critical Studies in Neurology. E & S Livingstone, Edinburgh & London, 1965.

With Gordon Holmes and James Taylor, edited Selected Writings of John Hughlings Jackson. 2 volumes, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1931-1932.

Neurological sections of Conybeare’s (1936) and Price’s (1937) Textbooks of Medicine.

References

- Walshe FMR. Some Problems Of Method In Neurology. . Canad. M. A. J 1953;68:21-29.

- Phillips CG. Francis Martin Rouse Walshe 1885-1973. Biogr Memoirs Royal Society. 1974. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/pdf/10.1098/rsbm.1974.0020

- Walshe FMR. The physiological significance of the reflex phenomena in spastic paralysis of lower limbs. Brain 1914; 37: 269–336.

- Walshe FMR. The giant cells of Betz, the motor cortex and the pyramidal tract: a critical review. Brain 1942 b; 65: 409–461.

- Walshe FMR. The anatomy and physiology of cutaneous sensibility: a critical review. Brain 1942a; 65: 48–114.

- Walshe FMR. The brain stem conceived as the ‘highest level’ of function in the nervous system; with particular reference to the ‘automatic apparatus’ of Carpenter (1850) and to the ‘centrencephalic integrating system’ of Penfield. Brain 1957; 80: 510–39.

- Walshe FMR. On the symptom-complexes of lethargic encephalitis with special reference to involuntary muscular contractions. Brain 1920; 43: 197–219.

- Pearce JMS. Sir Francis Walshe. J Med Biogr 2006;14:93-5

- Walshe FMR. The problem of the origin of the pyramidal tract. In: Scientific aspects of Neurology. Ed Hugh Garland. Edinburgh and London, E & S Livingstone1961. p. 15.

- Walshe, FMR. Diseases Of The Nervous System. Edinburgh E & S Livingstone 1947.

- Walshe FMR. Thoughts upon the equation of mind with brain’ Brain1953; 76: 1-18.

- British Medical Bulletin, 1945;3:3–5

- Critchley M. Sir Francis Walshe. (1886-1973). J Neurol Sci. 1973;19:255-6.

- Critchley M. The ventricle of memory. New York, Raven Press. p.193-207.

- Walshe FMR. Humanism, History, and Natural Science in Medicine The Linacre Lecture, E & S Livingstone, Edinburgh, 1950.

- Walshe Papers Reference code(s): GB 103 MS ADD 301. University College London.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is an Emeritus Consultant Neurologist Department of Neurology, Hull Royal Infirmary, and an author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Leave a Reply