Tony Ryan

Cork, Ireland

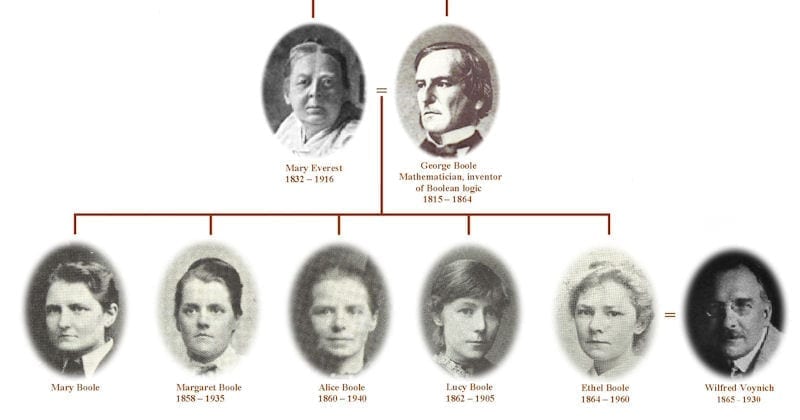

This is a story of a medical atlas, the author, the illustrator, and her great-uncle. The book, the Atlas of the Diseases of the Membrana Tympani, was written by Dr. Henry MacNaughton Jones in 1878. This atlas of diseases of the “eardrum” was illustrated by nurse and artist, Margaret Boole. This story also involves Sir George Everest (1790–1866), Surveyor General of India, who was an uncle of Margaret’s mother, Mary Everest Boole (figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. The Boole family tree. The Everest family name was pronounced “EVE rest.” Image: Kevin Boole, Boole – Ancestors and Descendants. Source. |

Margaret Boole was the second daughter of George Boole, foundation Professor of Mathematics at Queens College Cork, (now University College Cork). George Boole designed the true/false-as-1/0 algebraic system that underlies today’s computer circuits. Stephen Hawking included Boole among the seventeen most influential mathematicians from “the geometry of Euclid, through the calculus of Newton, the probabilities of LaPlace to the thoughts of Boole.”1

The Boole family lived in Lichfield Cottage, a Georgian cottage of Strawberry Hill Gothic design.2 The Boole daughters (figure 1) were all extremely talented.3,4 Two were scientifically inclined, while three were oriented towards the humanities.5 Alicia was a mathematician, and Lucy became the first woman Fellow of the London Institute of Chemistry. Mary Ellen, the eldest, was a published poet while the youngest sister, Ethel Lillian, was the author of a best-selling novel, The Gadfly. This sold many million copies in Russia alone because of its inspiring revolutionary themes, and was later made into a film with a soundtrack composed by Dmitri Shostakovich. She married Wilfred Voynich, discoverer of the mysterious Voynich Manuscript, an illustrated codex written in an unknown, and possibly meaningless, writing system.

|

|

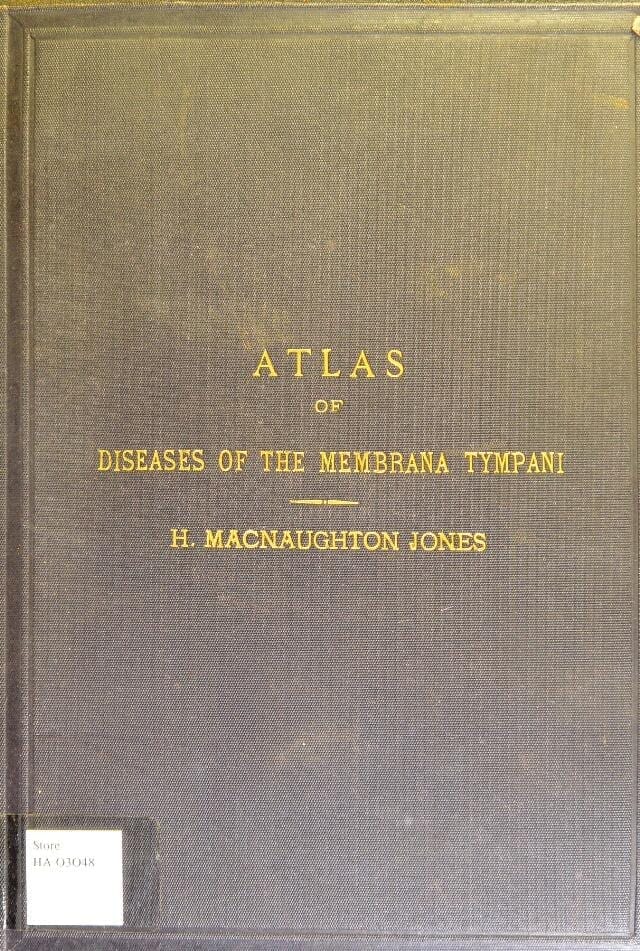

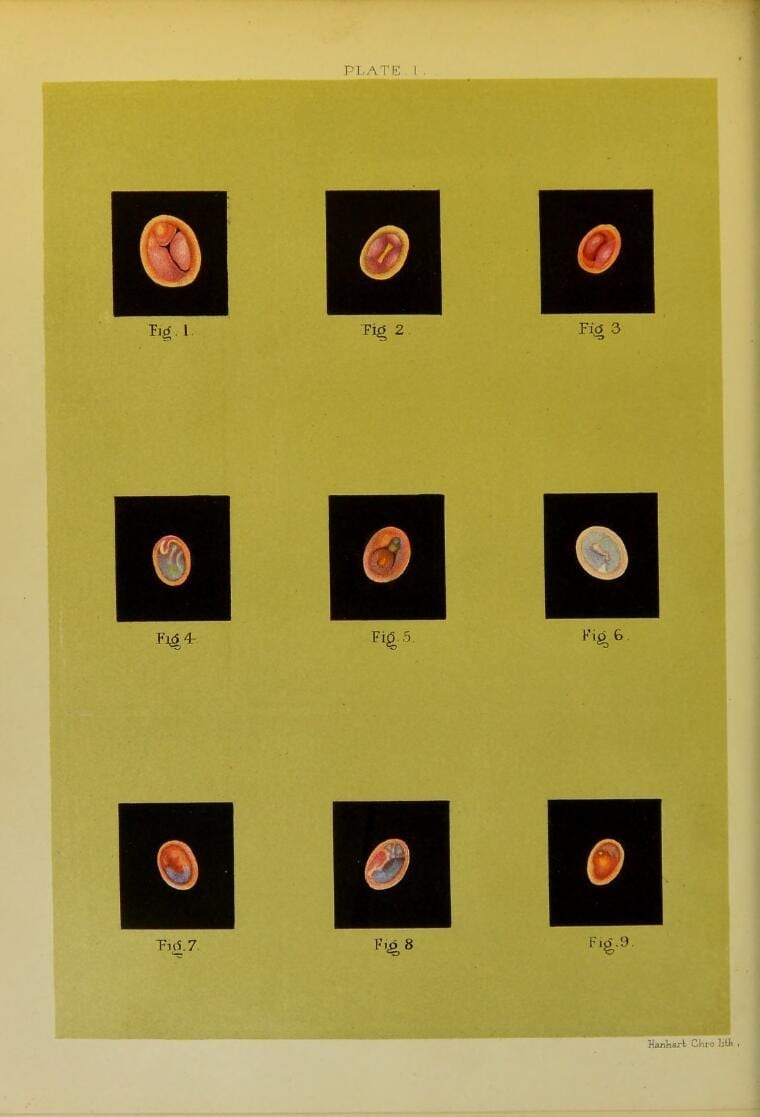

| Figure 2 a & b. Original front cover (a) and chromolithograph (b), from the Atlas of Diseases of the Membrana Tympani: London, J. & A. Churchill, New Burlington Street, 1878. Chromolithographs are signed by the Hanharts. Online copy from the Welcome Trust History of Medicine, Wellcome Collection. The original copy may be consulted at The University of Glasgow Library. Image Public Domain. | |

Margaret Boole was just six years of age when, along with her mother and her sisters, she left Ireland for London following the death of her father from pneumonia in December 1864. Ten years later, she returned to Ireland to train as a nurse in the Cork Ophthalmic and Aural Hospital founded by Dr. Henry MacNaughton Jones in 1868. However, she had other ambitions in addition to nursing. She proved to be a gifted artist and undertook formal studies at the Cork School of Art, gaining a prize in 1879.

Henry MacNaughton Jones (1844–1918) was born in Cork City, Ireland, and graduated with an MD at the Queen’s College, Cork in 1864, the year of George Boole’s death. His book, the Atlas of the Diseases of the Membrana Tympani, was published in 1878 (Philadelphia, Lindsay & Blakison).6 It contained his treatise on the diagnosis and management of aural afflictions, with fifty-four chromolithograph plates based on detailed color illustrations by Margaret Boole (figure 2).

While Dr. MacNaughton Jones examined the eyes, ears, and throats of the people of Cork, Margaret Boole peered into his instruments and drew colored illustrations of the incredible variety of ear pathology that affected the population at that time. As well as lending her artistic talents, Margaret Boole also afforded her nursing skills to the good doctor. Yet despite her major contributions, and perhaps a sign of the patriarchal Victorian times, her name did not appear on the book’s cover. Nor did her signature appear on any of the lithographic plates. Nevertheless, the author, MacNaughton Jones, gratefully acknowledged her contribution in the introduction:

I then had the advantage of having associated with me in the Cork Ophthalmic and Aural hospital one whose patience and assiduity were only equalled by her love of these special branches, and her peculiar aptitude both for the Aural and Ophthalmoscopic work to which she then devoted herself.

For the labour, care and patience, which she bestowed on these drawings, I cannot too heartily thank the artist, Miss M. Boole, to whose devotion to the study of the diseased conditions portrayed, and selected from a large number of aural patients, I am indebted for these most truthful representations.

|

| Figure 3. The cover of the Nidal Press edition of Atlas of Diseases of the Membrana Tympani showing what look like the Himalayas peaks along with the name of the author (but not that of the illustrator). |

He acknowledged that the atlas was truly a collaborative effort between the physician and artist:

All those chosen for this Atlas were completed under my constant supervision, and in no instance was a drawing of a membrane regarded as perfect until we were both fully satisfied of its being an unexaggerated as well as truthful of the diseased or abnormal condition. Thus at least I am enable to vouch for the strict accuracy of these drawings. Faithful representations have never been sacrificed for artistic effect.

Boole’s colored illustrations were turned into chromolithographs by Michael and Nicholas Hanhart, a London lithograph publishing house (1830–1902). MacNaughton Jones was well pleased with the work of the Hanharts, who used a complex layering of tint stones to produce work unique in coloration and tonal values (figure 2b). He wrote:

I was much afraid that a great difficulty would rise in the attempt (for the first time in this country) to lithograph the drawings, but Messrs Hanhart, who have for the publishers completed this part of the work, have exceeded, in the execution of these plates, my utmost expectations; and owing to their kindness in repeatedly visiting any figures not deemed perfectly satisfactory, they have produced copies not to be distinguished from the originals.

Following an online search we discovered, much to our surprise, a newly published edition of the atlas. Disappointingly, it turned out to be a bound photocopy of the book by Nabu Public Domain Reprints, with the original text intact but all Margaret Boole’s beautiful illustrations reduced to poor quality black-and-gray images. According to a stamp on an inner page, it appeared to have been copied from an original in the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine at Harvard. We were, however, intrigued by the cover artwork of the volume. It was bound with a color illustration of snow-covered peaks in what appeared to be the Himalayas, including perhaps Mount Everest, on a clear blue sky background.

|

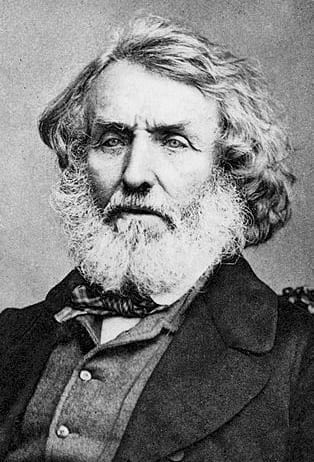

| Figure 4. Sir George Everest, Surveyor General of India. Photo by Maull & Polyblank, before 1866. Via Wikimedia. |

Mount Everest, the world’s highest mountain, was named after George Everest, Margaret Boole’s maternal grand-uncle (figure 4). He was the eldest son and third of six children born in Greenwich, London. He was educated at the Royal Military College in Marlow, England, and commissioned as a second lieutenant into the Bengal Artillery in India in 1806. He rose through the ranks and became Surveyor General of India.7

According to his biographer John Keay, George Everest was a cantankerous genius of a man who overrode ill health, native sensibilities, and the difficulties of India’s terrain and climate to complete a mammoth task of scientific enquiry and imperial drive.8 His great achievement was to complete, in 1843, Colonel William Lambton’s Great Trigonometric Survey, which mapped the spine of India from its southern tip to the Himalayas, a meridian known as the Great Arc. This great project set the scene for the British conquest of India and the foundation of its Victorian empire. The trigger for ultimate conquest was the Indian Mutiny of 1857, which led to a massive construction of roads, railways, telegraph lines, and canals throughout India, all of which depended heavily on the accuracy of the maps which the Great Arc had made possible.

Everest was responsible for appointing Andrew Scott Waugh as the Surveyor for India and it was Waugh who made the first formal observations of the mountain he called Mont (sic) Everest. In March 1856, Waugh wrote to the Royal Geographical Society to announce that the mountain was believed to be the highest in the world, and proposed that it be named “after my illustrious predecessor” as it was “without any local name that we can discover.” The ever restless George Everest never saw the mountain that bears his name. His achievements are largely forgotten in history, but “his name is just a little nearer the stars than that of any other lover of the eternal glory of the mountains.”7

We wondered if some Boolean scholar in Nidal press, with knowledge of the family tree, had paid a subtle tribute to Margaret Boole by placing Mount Everest on the cover of their reprint of the atlas. However, a further search showed that this publisher reprinted a number of public domain titles, with this same image as cover art. We must therefore conclude that the Atlas cover art was just a coincidence, not an acknowledgment to Margaret Boole’s ancestor or indirectly to the artist herself.

When Margaret Boole returned to London in the early 1880s, she worked as an ophthalmological artist at Moorfield’s Eye Hospital where her watercolors and drawings of the retina were published in the Transactions of the Ophthalmic Society of the UK (1883–86). She met her husband, Edward Ingram Taylor, at the Slade School of Art and they married in 1885. They had two children, Geoffrey, a scientist, and Julian, a surgeon. Despite her accomplishments, she apparently regarded her life as somewhat a failure compared to her brilliant sisters.2 Perhaps if she had received due recognition for her remarkable artistic talents during her lifetime, this would not have been the case.

References

- Hawking, S. God Created the Integers: The Mathematical Breakthroughs That Changed History. Running Press Book Publishers, 2005, p. 1160. ISBN 0-7624-1922-9.

- https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/20868114/lichfield-cottage-blackrock-road-ballintemple-blackrock-cork-city

- MacHale D. The Life and Work of George Boole: A Prelude to the Digital Age. Cork University Press, 2016.

- MacHale D, Cohen Y. New Light on George Boole. Cork University Press, 2018.

- Kennedy G. The Booles and the Hintons: Two Dynasties that Helped Change the Modern World. Cork University Press, 2016.

- https://wellcomecollection.org/works/rd2awwjt/items?langCode=eng&sierraId=b21468825&canvas=67

- Sir George Everest. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Everest

- Keay J. The Great Arc: The Dramatic Tale of How India was Mapped and Everest was Named. Ed Harper Collins, 2000.

TONY RYAN, MB, MD, FRCPI, MAHTL, is a Consultant Neonatologist following 25 years at Cork University Maternity Hospital, and an Associate Professor in the Department of Paediatrics & Child Health at University College Cork, Ireland. Having raised his own family with his wife, JoAnn, in Lichfield Cottage, Ballintemple, Tony’s interest in the Boole family has been stimulated by the fact that Lichfield Cottage was the Boole’s family home until the premature death of their father, George Boole, founder of Boolean Algebra, from pneumonia in 1864, leaving behind his wife, Mary Everest Boole and five young talented daughters.

Fall 2020 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply