George Venters

Scotland

|

| The “Old Surgical Hospital” as it is today. Courtesy of Dr. Iain MacIntyre. |

Faced with the danger of having his right foot amputated in 1873, the real “Long John Silver,” the English poet William E. Henley, turned for help to Joseph Lister and became a patient in the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. While there he was introduced to the Scots writer Robert Louis Stevenson. Born within a year of each other, they were kindred spirits. Companions in the adversity of chronic disease,1 they quickly became bosom friends and for the next decade worked together. Henley was the inspiration for the charismatic pirate cook Long John Silver in Stevenson’s most successful novel, Treasure Island. After its publication in 1883, Stevenson wrote to Henley, “I will now make a confession: It was the sight of your maimed strength and masterfulness that begot Long John Silver . . .”

The “Pirate”

Born the eldest of six children in Gloucester in 1849, Henley was brought up and schooled there.2 His headmaster, Thomas Edward Brown, was a distinguished academic and minor poet who became a lifelong friend and inspiration. He sowed the seeds of Henley’s career as a writer.

Suffering from bone tuberculosis since the age of twelve, Henley eventually had a below knee amputation at St. Bartholomew’s, London, when he was sixteen. It is easy to imagine how hard this was to bear. The pain of abscesses and their treatment, the frustration of being intermittently confined to bed, and the despair of finally losing a leg could have corroded the spirit of the strongest of individuals. Yet Henley did not buckle. His younger brother Joseph recalled how, as a youth, after his joints were drained, he would “hop about the room, laughing loudly and playing with zest to pretend he was beyond the reach of pain.” This indomitable spirit never left him. When local surgeons said that his right foot should also be amputated, he demurred and looked for advice elsewhere. At that time, the surgeons of the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh had a reputation second-to-none for surgical competence, so there he went.

The Place

Edinburgh University had established a Faculty of Medicine in 1726. From the outset, its teaching was modeled on Herman Boerhaave in Leiden, Holland. Instruction at the bedside of the patient was an essential part of his approach, however Edinburgh did not have a hospital. Fortunately, at that time there was a movement developing across the United Kingdom to set up charitable hospitals to treat the sick poor. Money was obtained from voluntary subscriptions by the public, and the Edinburgh establishment decided to set up the first voluntary hospital in Scotland and make it a teaching one from the start.3

In 1729 the Edinburgh Hospital for the Sick Poor opened with six beds in a house on a narrow street near the University. From these modest beginnings it grew over the next hundred years, propelled by rising demand and increasing prosperity in Scotland. It received a royal charter in 1736 as the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, and the first purpose-built new hospital admitted patients beginning December 1741. Designed to house 228 patients and built in sections as money became available, it was completed in 1748.

|

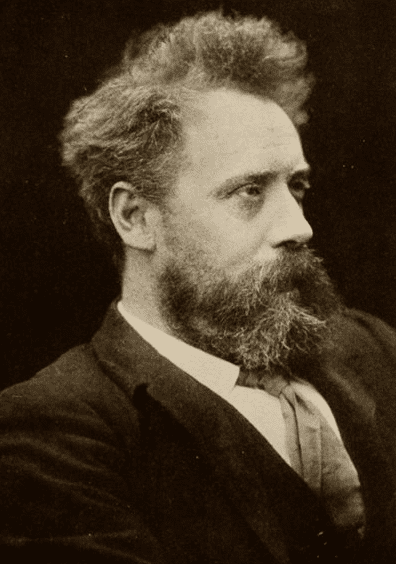

| Portrait of W.E. Henley. From The story of the House of Cassell. Via Wikimedia Commons |

By the end of the eighteenth century, it needed more beds. The adjacent school building became available and was incorporated for use as an additional surgical hospital in November 1832. This added a further seventy-seven beds and reflected the increasing importance of Edinburgh as a leading center for the development of surgery as a scientific discipline and meticulous craft as exemplified and led by James Syme.4

In the middle years of the nineteenth century, in addition to playing a key role in the development and promotion of effective general anesthesia, Edinburgh led the way in the control of operative infection because of the work of Joseph Lister. It was to him that Henley turned in 1873, hoping those techniques could save his foot, and they did. For the next two years the surgical hospital became Henley’s home and a place where his life would be changed for the better.

Two years is a long time for an ambitious young man to be contained in what he called “half workhouse, half jail.” But Henley made the most of it. Intelligent, creative, and industrious, he taught himself French, German, and Spanish. He corresponded widely with other writers and wrote himself, laying the foundation for a successful literary career as a poet, critic, and editor. At Edinburgh he started to become the force of nature, described by Lloyd Osbourne, Stevenson’s stepson, as “a great, glowing, massive-shouldered fellow with a big red beard and a crutch; jovial, astoundingly clever, and with a laugh that rolled like music; he had an unimaginable fire and vitality; he swept one off one’s feet.”5 There he also crafted his legacy to the Infirmary.

The Legacy

This was the volume of poetry In Hospital, published as “a Book of Verses.”6 It chronicles the world of the Royal Infirmary as seen through the eyes of a perceptive poet, looking deeply into the human condition, vividly evoking the realities of the lives of the people passing through it. Henley captured the immediacies of care 150 years ago by quickly pulling the reader into his present situation and our past history. By chance, he arrived there at a pivotal time when hospitals were transforming into the kind of institutions we recognize today. The sequence of poems roughly follows the trajectory of his treatment describing the place and the people who inhabit it.

The Setting

Early on a chilly summer morning he approaches

“the Hospital, grey, quiet, old, A tragic meanness seems so to environ

These corridors and stairs of stone and iron,

Cold, naked, clean—half-workhouse and half-jail”

The echoes of its former life as an austere Georgian High School resonate in this description. It was then nearly a hundred years old and it still stands today, having reverted to another place of learning. It is now home to the University of Edinburgh Centre for Carbon Innovation, which leads research in climate change. The description of the interior gaslit ward—“gaunt brown walls Look infinite in their decent meanness”—is redolent of its 1839 refurbishment, as is the absence of a human touch: “There is nothing of home in the noisy kettle. . . . The fulsome fire.”

|

| Portrait of Mrs. Janet Porter, the “Staff Nurse, Old-style.” Courtesy of Lothian Health Board Archive |

Patients are both characters in the story and part of the scenery: “A small, strange child—so agèd yet so young!—Her little arm besplinted and beslung”; “A poor old tramp explains his poor old ulcers”; “The bad burn waits with his head unbandaged”; “The patients yawn, Or lie as in training for shroud and coffin.” In short, “a gruesome world.”

The People

Henley stitches together the episodes of his own journey while also telling the stories of other patients and painting pictures of those he sees as essential workers. His visitors, particularly Robert Louis Stevenson, also impact his writing. The shadow of death loiters around many a corner. It is given a poem to itself, “Ave Caesar!”, an allusion to the quasi-gladiatorial situation of patients facing death.

The chosen patients’ stories reflect the drama, despair, and tragedies of the time in “Casualty,” “Suicide,” and tuberculosis in “Etching.”

He is also a shrewd commentator on the cast of medical and nursing staff. His debt to “The Chief” is written as an affectionate, well-deserved paean to Lister. The “House Surgeon” is similarly well-regarded, both for his clear merits and also his age. (He was only a few years older than the “Musketeers” as Henley called the trio of himself, Stevenson, and Charles Baxter, a young lawyer who shared his journey.7) The only doctor he does not favor is “The Professor,” seeing him as a showman with a motley student throng trailing behind him who is casually cruel to “Case One.” The only student given a name is “Louis,” (Robert Louis Stevenson) who is given a poem to himself, “The Apparition”: “. . . a spirit intense and rare . . . valiant in velvet, light in ragged luck . . . a deal of Ariel . . . of Hamlet most of all.”

Most of the women he describes, the “Staff nurse, Old-style,” the “New,” and the “Probationer” are working in a profession that is in the midst of a major change. By then Florence Nightingale had evangelized the Infirmary and systematically trained well-educated women who were coming to the fore. But the bulk of care was given by nurses and others whose expertise came from experience. The Staff Nurse, “Old-style,” was revered:8 “The doctors love her, tease her, use her skill.” And Henley also saw the worth of the Irish “Scrubber” (the ward cleaner): “. . . .you shall find No rougher, quainter speech, nor kinder heart.”

While this was his first published volume, it was generally well received, though some prudish critics thought it strong meat for “refined” Victorian taste. It deserved approval, for it distilled and displayed the essence of the Infirmary, that compassionate caring which persists to the present day. An image in the poem “Vigil” —a cri de coeur about sleeplessness—conjures this, as in the wee small hours of the morning an insomniac Henley sees, peering at him through half lit dark;

“the night-nurse,

Noiseless and strange, . . . . (Whispering me, ‘Are ye no sleepin’ yet?’).”

And still centuries later, every night, even in the third purpose-built Royal Infirmary, some poor sleepless soul will take comfort in being watched over by a kind, vigilant nurse asking that selfsame question.

End Notes

- “Robert Louis Stevenson and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia” Sally Metzler, Hektoen International Journal, 12 issue 3, summer 2020. Robert Louis Stevenson and hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia,

- There are a number of readily accessible summary biographies on W. E. Henley on the internet. The one I used most was: Wikipedia; 6/10/2020;30/10/2020: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Ernest_Henley

- Story of a Great Hospital. The Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh 1729 -1929, A Logan Turner. Edinburgh, 1979.

- William Ernest Henley, English Poet, Critic, Fditor; Peoplepill.com. 1/12020;4/11/20. https://peoplepill.com/people/william-ernest-henley/

- “James Syme, the Napoleon of Surgery, 1799-1870” George Dunea, Hektoen International Journal, 11 issue 3, summer 2019. https://hekint.org/2019/06/28/james-syme-the-napoleon-of-surgery-

- The first collection of Henley’s poems was compiled by Alfred Nutt and published in 1888 as “A Book of Verses”. The edition I used was the 1907 volume “Poems” edited by David Nutt and available as a free download in Project Gutenburg. Project Gutenburg;2/27/2015;10/30/2020; https://dev.gutenberg.org/files/1568/1568-h/1568-h.htm

- The “Envoi” written in 1888 and included as a postscript to the “!n Hospitals” volume gives Henley’s recollections of the times they shared and closeness of the friendship of the three young men when he was in the ward. Clearly they enjoyed each other’s company.

- The Staff Nurse is identifiable as Mrs. Janet Porter who is mentioned in Logan Turner’s book, (loc cit).

Acknowledgments

I am extremely grateful to my wife Vivien and son Colin for keeping me focused and curbing my verbosity; to Dr. Iain MacIntyre for checking matters of fact, making useful suggestions on the text, and generously providing the images of the old surgical hospital building as it is today and of Mrs. Janet Porter.

GEORGE A. VENTERS, MBChB, DipAnGen, PhD, FFPHM., is a retired Consultant in Public Health Medicine who was a lecturer in Trinity College Dublin and Aberdeen University, then a Consultant on Lothian and Lanarkshire Health Boards. His main responsibilities have been in medical information systems, epidemiology, and health service planning. Since retirement, he has developed an interest in community history.

Fall 2020 | Sections | Hospitals of Note

Leave a Reply