Nicolás Roberto Robles

Badajoz, Spain

|

|

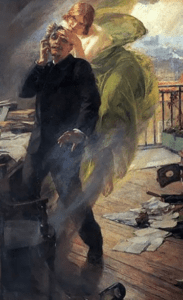

Figure 1. Green Muse. Albert Maignan. 1895. Via Wikimedia Commons |

“After the first glass of absinthe you see things as you wish they were. After the second you see them as they are not. Finally, you see things as they really are, and that is the most horrible thing in the world.”

-Oscar Wilde

|

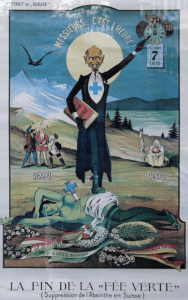

| Figure 2. La fin de la fée verte (“The End of the Green Fairy”): Swiss poster about the country’s ban of absinthe in 1910. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia |

Absinthe is a spirit with very high alcohol content (usually 55%, but as high as 89.9%) and an anise flavor. Derived from herbs, including wormwood leaves, absinthe was originally considered to be similar to other medicinal herbal preparations such as the German wermut, or vermouth. Absinthe is easily distinguished from other alcoholic beverages because of its natural green color and was given the moniker of “Fée Verte” (Green Fairy). At one time it was considered to be highly addictive because it contains a compound called thujone. Valentin Magnan, a nineteenth-century French psychiatrist, discovered that pure wormwood oil caused seizures in animals independent from the effects of alcohol. Based on this, absinthe, which contains a small amount of wormwood oil, was assumed to be more dangerous than ordinary alcohol. Magnan later studied effects in humans and claimed that heavy drinkers who consumed absinthe had seizures and hallucinations.1 In light of modern evidence, and Magnan’s personal belief that alcohol and absinthe were degenerating the French, these results are questionable. Absinthe was even claimed to have provoked Vincent Van Gogh to cut off his ear. Because of these claims, absinthe was banned in most European countries and the United States by 1915. The most popular trademark was Pernod Fils.

Thujone is a ketone and a monoterpene that occurs naturally in two epimeric forms. The differences between them are small but meaningful because alpha-thujone is considered more toxic.2 It has an odor like that of menthol, which is found in mint. Thujone is found in a number of plants, such as arborvitae (genus Thuja, hence the derivation of the name), Nootka cypress, some junipers, mugwort, oregano, common sage, tansy, and wormwood, most notably grand wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). It is also found in various species of Mentha (mint). Though it is best known as a chemical compound in the spirit absinthe, the small quantity present is unlikely to be responsible for the drink’s alleged stimulant and psychoactive effects. Thujone acts on GABA receptors as an antagonist, which is opposite to the effects of alcohol. While α-thujone can cause convulsions and death when administered in large amounts to animals and humans, there is only one case of documented wormwood toxicity involving a thirty-one-year-old man who drank 10 mL of steam-distilled volatile oil of wormwood, wrongly believing it was absinthe liqueur.3 Medicinal extracts of wormwood have not been shown to cause seizures or other adverse effects at usual doses.4

Absinthe was especially popular among artists. The greatest nineteenth-century French poets, including Alfred de Musset, Charles Baudelaire, Arthur Rimbaud, and Paul Verlaine, were avid consumers of this drink. Verlaine is said to have drunk himself to death and damned absinthe from his deathbed. Rimbaud called absinthe the “sagebrush of the glaciers” because the bitter-tasting wormwood is plentiful in icy Val-de-Travers, Switzerland. Alfred Jarry, the author of Ubu Roi, was so obsessed with absinthe that he had five or six drinks per day that he refused to dilute with water. He referred to it as “the Green Goddess,” “the Sacred Herb,” and “the Holy Water” and even painted his hair, face, and hands green in homage to “the Essence of Life.”

|

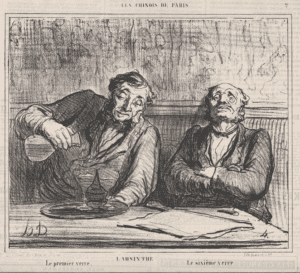

| Figure 3. Absinthe: The first glass, the sixth glass, from ‘The Chinese of Paris,” published in Le Charivari. Honoré Daumier. December 22, 1863. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

In the poem “Poison” from his 1857 volume The Flowers of Evil, Charles Baudelaire ranked absinthe ahead of wine and opium:

Tout cela ne vaut pas le poison qui découle

De tes yeux, de tes yeux verts,

Lacs où mon âme tremble et se voit à l’envers . . .

Mes songes viennent en foule

Pour se désaltérer à ces gouffres amers.

All that is not equal to the poison which flows

From your eyes, from your green eyes,

Lakes where my soul trembles and sees its evil side . . .

My dreams come in multitude

To slake their thirst in those bitter gulfs.

Another poem about absinthe is attributed to Alfred de Musset and was published in the French journal Le Gaulois du Dimanche in 1905 (de Musset died in 1857). By the age of twenty, his literary fame and diabolic reputation were both rising. He likely sketched out these verses on a coffee table in a group of friends:

Salut, verte liqueur, Némésis de l’orgie!

Bien souvent, en passant sur ma lèvre rougie,

Tu m’as donné l’ivresse et l’oubli de mes maux;

J’ai vu plus d’un géant pâlir sous ton étreinte!

Salut, sœur de la Mort! Apportez de l’absinthe;

Qu’on la verse à grands flots!

Hey, green liquor, orgy nemesis!

Very often passing over my reddened lip,

You gave me drunkenness and forgetfulness of my ailments;

I’ve seen more than one giant grow pale under your embrace!

Hello, sister of Death! Bring some absinthe;

Let it be poured in with great drinks!

There is no official record that these verses were written by de Musset, although some have suggested a resemblance to his other works. The final form may have been distorted by the memory of the copyist.

Absinthe had a revival in the 1990s, especially in countries where it was never banned, such as Spain. It was said that Hemingway could only face a bull “after drinking three or four absinthes, which, while they inflamed my courage, slightly distorted my reflexes.” In 2000, “La Fée Absinthe” became the first commercial absinthe distilled and bottled in France since the 1914 ban.

References

- Conrad III, Barnaby. Absinthe: History in a Bottle. San Francisco (USA). Chronicle books.1988. Pg. 101-105

- Höld KM, Sirisoma NS, Ikeda T, Narahashi T, Casida JE. Alpha-thujone (the active component of absinthe): gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptor modulation and metabolic detoxification. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97(8):3826-3831.

- Weisbord SD, Soule JB, Kimmel PL. “Poison on line – acute renal failure caused by oil of wormwood purchased through the internet”. N. Engl. J. Med. 1997; 337 (12): 825–827.

- Yarnell E, Heron S. “Retrospective analysis of the safety of bitter herbs with an emphasis on Artemisia absinthium L (wormwood)”. J. Naturopathic Med. 2000; 9: 32–39.

NICOLÁS ROBERTO ROBLES is a professor of Nephrology at the University of Extremadura.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 13, Issue 3– Summer 2021

Fall 2020 | Sections | Science

Leave a Reply