JMS Pearce

Hull, England

|

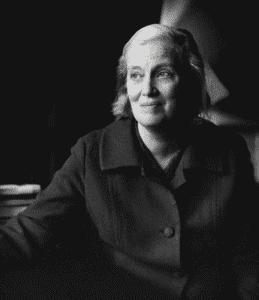

| Fig 1: Dorothy Hodgkin. by Godfrey Argent. National Portrait Gallery, London. CC BY-NC-ND 3.0. |

Dorothy Hodgkin (Fig 1), though not by religion, had close Quaker affinities through her marriage and through her spirited pacifism.

She possessed a unique mixture of scientific skills that allowed her to extend the use of X-rays to reveal the structures of compounds, a technical venture far more complex than anything attempted before. She became a pioneer of protein crystallography.1

Dorothy was the eldest of the four daughters of John Winter Crowfoot (1873-1958) and his wife, Grace Mary (Molly) Hood (1877-1957). The Crowfoots came from Beccles in Suffolk, where many of her father’s relatives were doctors. Dorothy Crowfoot attended the Grammar School in Beccles.2 Aged ten, after observing crystals formed from copper sulfate and alum, she was inspired and later wrote: “I was captured for life, by chemistry and by crystals.” For her sixteenth birthday her mother gave her a book by the renowned Sir William Henry Bragg, entitled, Concerning the Nature of Things, which explained how X-ray diffraction could show the arrangement of atoms in crystals. This idea underwrote her future fundamental research and discoveries.

She read chemistry at Somerville College, Oxford, obtaining first class honors, and then worked as a research student at Cambridge for John Desmond Bernal; there she developed her interest in x-ray crystallography to demonstrate the structure of proteins and sterols. She greatly admired him, nicknaming him “Sage.”

She returned to Oxford in 1934, completing her PhD on sterols. Sir William Bragg in 1937 invited her to the Royal Institution to try to advance her Oxford investigations of the insulin molecule by crystallography.3

In 1937 she married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin (1910-1982) educationalist, author, and Marxist. He was a Quaker, son of Robin H. Hodgkin, provost of Queen’s College, Oxford, and cousin of A.L. Hodgkin, the Nobel Prize winner for Medicine. Dorothy was attracted to socialist politics on humanitarian grounds, advocating world peace, resolution of conflicts by meetings of prominent scientists, and alleviation of the economically downtrodden. She epitomized traditional Quaker values but did not formally belong to the Society of Friends.

|

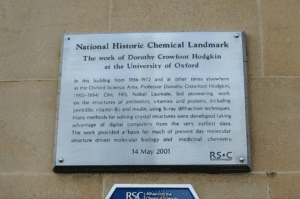

| Fig 2: 2001 memorial tablet by the Royal Society of Chemistry. Photo by Luca Borghi. Source |

One morning in May 1940, Hodgkin had a chance meeting with an unusually animated Ernst Chain in Oxford. Chain and his colleague Howard Florey had just demonstrated the efficacy of penicillin against bacterial infections, but its chemical formula and how to synthesize it were unknown. Hodgkin took up the challenge using X-ray diffraction techniques (Fig 2). Five years later on VE Day in 1945, with thousands of people packing the streets to celebrate, Dorothy Hodgkin clutched a model of wires and corks amidst cheering crowds—Penicillin. As Ernst Chain said in his Nobel Lecture:

“For the first time the structure of a whole molecule has been calculated from X-ray data, and it is the more remarkable that this should have been possible in the case of a substance having the complexity of the penicillin molecule.”

This knowledge of the structure4 finally allowed the synthesis of pure penicillin and its many derivatives: ampicillin and the cephalosporins, which formed the foundations of future antibiotic treatments.

In 1955-57, she published the structure of vitamin B12, the vitamin deficient in pernicious anemia.5 She was rewarded with the Nobel Prize in 1964 for this work—only the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, after Marie Curie and her daughter Irene.

In Oxford the family home was a flat on Bradmore Road that belonged to Thomas Hodgkin’s parents; he was frequently away from home in his teaching work in Britain and in Africa. In 1957 they took a house on Woodstock Road with Dorothy’s sister Joan, where many eminent scientists and friends visited them. Thomas died in March 1982.

When she retired, she continued to work for world peace. In her lifetime, despite severe rheumatoid arthritis, she determined the three-dimensional structures of cholesterol, penicillin, vitamin B12, lactoglobulin, ferritin, and insulin—all major medical advances.1

Not until 1946 was she made a Fellow of the Royal Society, and in 1976 she was awarded its Copley Medal. In 1965, she became the first woman to receive the Order of Merit and, in 1976 became Chancellor of Bristol University, and President of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. Nominated by her friend Linus Pauling, she also received the Lenin Peace Prize.

She became president of the pacifist Pugwash Conferences founded, amongst others, by Bertrand Russell and Albert Einstein, which aimed at bringing together scientists from across the world to foster disarmament.

She died of a stroke in the lovely Cotswold village of Shipston-on-Stour on 29 July 1994. She was buried in the churchyard of St. Mary the Virgin in Ilmington. In his address Max Perutz said:

Dorothy will be remembered as a great chemist, a saintly, tolerant and gentle lover of people and a devoted protagonist of peace.

*****

[This account is based on Pearce JMS. Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin. In: Quakers in Medicine, ‘Friends of the Truth’, Sessions of York, Ebor Press 2009.]

References

- Ferry, G. Dorothy Hodgkin. A life. London, Granta,1998.

- Georgina Ferry, ‘Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot (1910–1994)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/55028.]

- Crowfoot D. ‘X-ray single crystal photographs of insulin’, Nature, 135, 1935, 591-2.

- Hodgkin, Dorothy Crowfoot: The X-ray analysis of complicated molecules. Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1964.

- Howard J A K. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology. London: Nov 2003. Vol. 4, Iss. 11; p. 891=6.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is an Emeritus Consultant Neurologist Department of Neurology, Hull Royal Infirmary, and an author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Leave a Reply