Margaret B. Mitchell

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Graham M. Attipoe

Nashville, Tennessee, United States

|

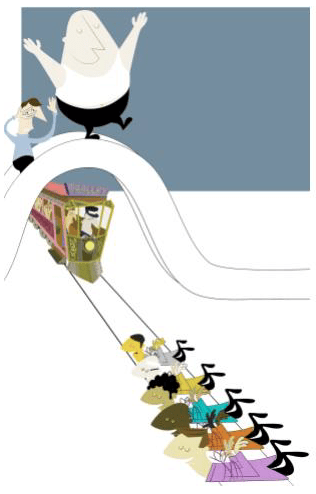

| Bridge situation. John Holbo. 2010. CC BY-NC 2.0. Via Flickr |

The “Trolley Problem”

Originally described by Philipa Foot in 1967, the “Trolley Problem” is an ethical dilemma commonly taught in philosophy that challenges participants to explore how far they would go to save lives:

A trolley is barreling down a set of tracks towards a group of five people, endangering their lives. Over the tracks is a bridge with a man standing on it. If he is pushed off the bridge and falls onto the tracks, he would be killed. However, his fall and death would stop the trolley and spare the lives of the five people in the distance. Should you push this man off the bridge?

This scenario prompts discussions that weave together different ethical frameworks such as utilitarianism, non-maleficence, and justice.1 It has been applied to situations in public health,2, 3 highlighting the inherent tensions in forced decisions that affect several lives. The COVID-19 pandemic provides a unique landscape in which to apply this dilemma: perhaps the virus itself is representative of the trolley, barreling down the tracks towards millions of people. But the application of this analogy to the current context begs several difficult questions, including: if the virus is analogous to the trolley, who is being pushed off the bridge?

Sacrifice in a pandemic

Perhaps one answer surfaced with the early news of deaths of healthcare workers infected with COVID-19 while treating patients.4 Stories from the frontlines revealed the emotional and psychological trauma inflicted on medical workers, even those who were not physically afflicted with the virus themselves.5-7 As more data has been released detailing the devastating impact of COVID-19 in communities of essential workers,8 the uneven distribution of the burden of this pandemic both inside and outside of hospital walls has become clear.9

But in addition to bearing a direct physical burden of risk, epidemiological experts have called for different kinds of individual sacrifices. The economic consequences have been devastating: unemployment levels are climbing,10 and some small business owners have been forced to close their doors, threatening their financial security and long-term viability.11 For individuals, wearing a mask outside the home may be uncomfortable both physically and socially, acting as a daily reminder of the potential danger each person represents.

Choices that sacrifice one’s comfort and daily routine, such as choosing to get a takeout meal instead of dining in, moving a social gathering outside, or wearing a mask to the grocery store, lower the risk for environmental spread of disease and thus play a role in slowing down and eventually stopping our metaphorical trolley, COVID-19. These actions, however, stand in stark contrast to the sacrifice required in the analogy, the person who is pushed off a bridge and loses his life.

|

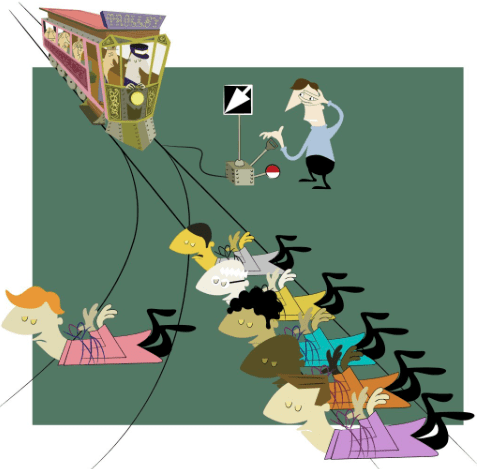

| Basic trolley scenario. John Holbo. 2010. CC BY-NC 2.0. Via Flickr |

The “Trolley Problem”: version #2

To resolve this misalignment, consider a second version of the “Trolley Problem”:

In lieu of standing on a bridge over the tracks, you are standing on the side of the tracks next to a switch. The trolley is currently on this same set of tracks such that it will hit and kill five people. You have the option to flip a switch, which will change the trolley’s course, such that the trolley will only hit and kill one person. Would you flip that switch?1

In this version, the action taken to save four lives is different—less personal, active, and direct. A strict utilitarian, someone who believes in “the greatest good for the greatest number,”12 may see these two versions as equivalent in terms of outcomes (four lives saved either way). However, many people respond differently to these two scenarios13 because the outcome matters just as much as the means. People often find less guilt associated with flipping a switch than having to push a person off of a bridge.14 Ethicists call this phenomenon the Principle of Double Effect, which suggests that causing harm indirectly (flipping a switch) is permissible if for the greater good, while directly causing harm (pushing the man), even if for a greater good, is not permissible.1

Principle of Double Effect

This notion that harmful actions inflicted by different means elicit opposing emotional responses, even if inflicted for the same outcome, is crucial in a scenario where an array of sacrifices are necessary for the greater good. Those on the frontlines may feel as if they are being asked to dive in front of a trolley to benefit those unable to get off the tracks. The invisible enemy may not be as conspicuous as a runaway train, but healthcare workers have witnessed its deadly threat firsthand. The sacrifice of these doctors and nurses is direct and obvious, both to them and to the public. And knowingly placing these people directly in harm’s way, especially if without proper protective equipment, carries an emotional gravity and a heavy weight on the shoulders responsible.

But as states move to reopen businesses, decisions made on a larger scale, such as sending people back into work, or at an individual level, like forgetting to wear a mask to the grocery store, may lack the same sense of guilt and culpability. Importantly, there is both physical and temporal separation between the action and the effect—as a possible asymptomatic carrier walking in public, a secondarily infected person will not fall ill and die immediately. Out of sight, that person may become both a memory and a statistic without the carrier ever knowing. Certainly the human tendency to value experiences differently in the present versus the future is well-described in economics, as future financial gains are often discounted compared to financial gains realized in the present.15 Do you humans discount future and more distant, impersonal human suffering as well?

In addition to the temporal and physical separation between cause and effect, both the “Trolley Problem” and COVID-19 introduce another mechanism at work—an opportunity to evade guilt by a lack of knowledge of the eventual outcome. In the first version of the “Trolley Problem,” the culpability is obvious and the guilt inevitable, as pushing a man off the bridge requires this participant to be present and witness the gruesome scene to come. But perhaps, in the second case, the trolley comes barreling down the tracks a week later, and the person who flipped the switch is not around to see what happened. The preference of people for this latter option1 has a troubling implication—are people are more likely to inflict harm if somehow separated or insulated from the outcome?13, 14

|

| Photo by Ashkan Forouzani on Unsplash |

Policy implications

Remembering this phenomenon—that people may be more tolerant of harm with delayed and impersonal effects—is paramount in large-scale decision making. Leaders across the country may be making these decisions while physically and temporally distanced from the effects they will have. Policies will affect emergency department waiting rooms and intensive care units weeks or even months after the decisions are made. Is the pain felt at the funerals of the patients who will die as a result of these decisions felt in the rooms in which the decisions are made? And because these leaders may not represent their constituents in terms of socioeconomic status or race, they may also be socially and culturally distanced from the people most severely affected by this virus.

But this phenomenon is also individually important in terms of the silent, thankless sacrifices made every day: each decision to wear a mask or walk a few feet farther away from someone on the sidewalk may seem like it will not matter. Or if it matters, would anyone ever know? But this lack of connection between means and outcomes does not negate the power of the means themselves.

There are several key stakeholders and perspectives in this debate. While healthcare providers look in horror at falling oxygen saturation numbers, fearing mechanical ventilation may be inevitable, policymakers look in equal anguish at unemployment rates, knowing the economic devastation across the country. Moreover, this “Trolley Problem” is a simplistic analogy applied to an increasingly complex situation, and its forced dichotomy—that there are only two tracks—is not realistic, although sometimes this issue is framed as if saving the economy and saving lives are mutually exclusive goals.16

The application of this ethical quandary elucidates how the virus preys as much on the human tendency to devalue future, distant, and seemingly impersonal suffering as much as it preys on the cells of the respiratory tract. This dilemma also effectively demonstrates how sacrifices vary in visibility and overtness but not in their effect. Whether in the Oval Office or on a sidewalk, these silent and anonymous sacrifices—which may not seem like a direct part of saving lives—still play a key role in the health of so many.

The pandemic will not be over with the flip of a switch; nor will there be easy answers. But when we wander back to the trolley tracks a year from now, will we be proud of our choices?

References

- Andrade, G. Medical ethics and the trolley problem. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2019; 12:3.

- Manthous, C.E. Emergency surgery, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and the trolley problem. J Crit Care. 2014 Feb;29(1):170-1.

- Epting, S. A Different Trolley Problem: The Limits of Environmental Justice and the Promise of Complex Moral Assessments for Transportational Infrastructure. Sci Eng Ethics. 2016 Dec;22(6):1781-1795.

- In Memoriam: Healthcare Workers Who Have Died of COVID-19. Medscape Medical News. WebMD. Accessed June 25, 2020.

- Jayawardena, A. “Waiting for Something Positive.” NEJM. 2020;382;e89.

- Hoffman, J. ‘I Can’t Turn my Brain Off:’ PTSD and Burnout Threaten Medical Workers. The New York Times. May 16, 2020.

- Spoorthy, M.S., Pratapa S.K., & Mahant, S. Mental health problems faced by healthcare workers due to the COVID-10 pandemic-A review. Asian J Psychiatry. 2020 Jun; 51: 102119.

- Guasti, N. The plight of essential workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2020. 395:10237: 1587.

- Weekly Updates by Select Demographic and Geographic Characteristics: Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Accessed June 25, 2020 via https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid_weekly/index.htm.

- “The Unemployment Situation-May 2020.” Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. Accessed June 30, 2020 via https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/empsit.pdf.

- Bartik, A., Bertrand, M., & Cullen, Z., et al. How are small business adjusting to COVID-19? NBER Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. Accessed June 30, 2020 via http://www.nber.org/papers/w26989.

- The History of Utilitarianism. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Revised Sep 22, 2014. Accessed on June 30, 2020 via https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/.

- Shaver, R., Nuccetelli, S., & Seay, G. Ethical Naturalism. Ethical Non Naturalism and Experimental Philosophy. pp. 194–200. UK: Cambridge University Press. 2012.

- Tannsjo, T. Taking life: Three Theories on the Ethics of Killing. UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. p. 58, 63, 75.

- Brush, B.C. Risk, Discounting, and the Present Value of Future Earnings. Journal of Forensic Economics. Fall 2003.16(3):262-274.

- Bohoslavsky, J.P. COVID-19 Economy vs Human Rights: A Misleading Dichotomy. Health and Human Rights Journal. Published online April 20, 2020. Accessed June 30, 2020 via https://www.hhrjournal.org/2020/04/covid-19-economy-vs-human-rights-a-misleading-dichotomy/.

MARGARET B. MITCHELL, MD, MS-HPEd, is a current resident at Harvard Medical School/Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary in Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery and a recent graduate from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine with a Certificate of Distinction in Biomedical Ethics. She also completed a Masters of Health Professions Education from Mass. General Hospital’s Institute of Health Professions, and has a Bachelors in Economics from her undergraduate studies at Vanderbilt University. Her professional interests include surgical ethics, health economics and policy, as well as medical education.

GRAHAM M. ATTIPOE is a current medical student at Vanderbilt School of Medicine as well as MBA student at the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania. He completed his BS from Duke University with a major in Biology. His professional interests lie at the intersection of healthcare and various business and management strategies, specifically in cost-effectiveness, medical technology, and digital health.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to thank Jessica Goldenring, a PhD candidate in financial economics at Columbia University, for her assistance with this piece.

Leave a Reply