JMS Pearce

East Yorks, UK

|

| Fig 1. Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes. Reproduction after a pencil drawing by G. Shaw, 1957. Credit: Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) |

Mention the name Keynes in Britain and most people think of the Buckinghamshire town Milton Keynes or the celebrated twentieth-century economist John Maynard Keynes. In the thirteenth century Milton Keynes village was Mideltone Kaynes, named after its feudal masters, the de Cahainges originally from Normandy,1 who held many manors after the Norman Conquest. All the subsequent Keynes’ are scions of this family.2

Among the polymaths principally preoccupied with medicine and science, few excel Geoffrey Keynes (1887–1982) (Fig 1), a surgeon and literary scholar of great and varied learning. But history is fickle. Geoffrey Keynes has been overshadowed by his more famous older brother, the macroeconomist John Maynard Keynes. He commented without rancor that all his young days were lived “under the shadow of a far more forceful and intellectual character than my own . . . we were not close friends. . . .”1 (p. 19, 20)

Geoffrey Keynes achieved distinction in three areas: as an inventive surgeon; as a writer, editor, bibliographer, and the indisputable authority on William Blake; and as a valued trustee of the National Portrait Gallery.

He was born in Cambridge on 25 March 1887, the youngest child of John Neville Keynes, gold medalist in moral sciences and Fellow of Pembroke College, and Florence Ada. He attended Rugby School before gaining an exhibition to Pembroke College, Cambridge in 1906, obtaining a first in the Natural Sciences Tripos. He studied medicine at Bart’s from 1909, winning the surgical scholarship and the Willett Medal, graduating in 1913. At this time he saved Virginia Woolf’s life when she took an overdose of drugs. With Sir Henry Head he washed out her stomach and attended her closely until she recovered. Virginia Woolf later gave him the manuscript of her essay “On Being Ill” in gratitude for his professional care.

|

| Fig 2. Cover of The Gates of Memory |

He served with distinction at the front in the First World War. He returned to St. Bartholomew’s Hospital as chief assistant to Professor George Gask and soon was appointed to its surgical staff and to Mount Vernon Hospital. He built a thriving practice with a special interest in breast, thyroid, and hernia surgery. He served as personal assistant to Lord Moynihan, who had extended his practice from Leeds to London. He also performed all the thyroid surgery at New End Hospital, which he continued after retirement from Barts.

Surgical innovations

He made three major advances in surgery, each of which was groundbreaking, each enormously controversial, and each has passed the tests of time. He served in the trenches and in French military hospitals in the First World War, operating unimaginably long hours in dreadful surroundings on massive injuries. There he initiated blood transfusion, despite much opprobrium,a but this saved the lives of many soldiers. He developed a portable machine to store blood and facilitate transfusions. He introduced the technique at Bart’s in peacetime and wrote the first textbook Blood Transfusion in 1922. His experiences are detailed in his excellent autobiography, The Gates of Memory, published in 1981.

His second advance was in the 1930s when Professor George Gask at Bart’s “set him up” as his chief assistant to practice partial excision (lumpectomy) with radiotherapy for breast cancer in place of Halstead’s long-established radical mastectomy. His results matched the radical procedure with much less disfigurement, as he described: “I hated the practice of such barbarous mutilation of the female body and was delighted to find further evidence against its performance.” But “. . . My views were clearly unpalatable to most surgeons.”3 Partial mastectomy remains standard practice.

|

| Fig 3. Title page of The Anatomical Exercises of Dr. William Harvey |

In yet another field, following Blalock4 in 1949 he advocated and performed thymectomy for patients with myasthenia gravis5 who were resistant to Mary Walker’s physostigmine therapy, which she discovered in 1934.6,7 His first operation was in 1942; by the time he retired in 1956 Keynes had operated on 281 myasthenic patients.

In the Second World War he served in the Royal Air Force with the rank of acting air vice-marshal. He obtained numerous honors: three Hunterian professorships, the Cecil Joll Prize in 1953, and the Sir Arthur Sims Commonwealth traveling professorship. At the Royal College of Physicians he gave the Harveian Oration and was awarded the Wilkins Lecture at the Royal Society in 1967. He was appointed Knight Bachelor in 1955.8 Keynes worked tirelessly till retirement in 1951. He continued to lecture and wrote essays and a biography of William Harvey that received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize.

|

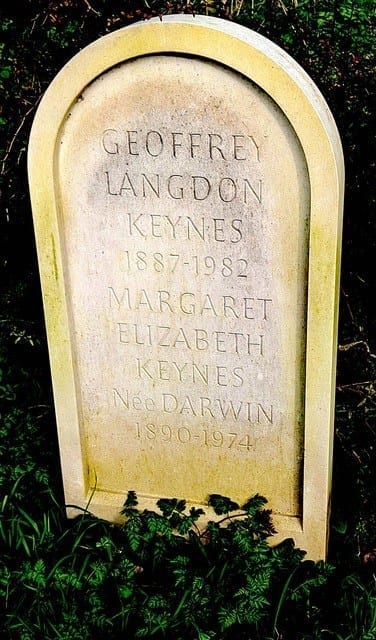

| Fig 4. Gravestone of Geoffrey and Margaret Keynes. |

Literary works

When not fully employed in surgical pursuits, Keynes had been an ardent bibliophile since his student days. When aged twenty, he was smitten by reading a copy of Blake’s Illustrations of the Book of Job, which he chanced upon in a bookshop. Thence followed a pursuit of William Blake and his works that became a major interest in his life; he became the leading authority,9 culminating in a huge Bibliography of Blake and the foundation of the Blake Trust.

He published many bibliographies of such titans as Robert Hooke, John Evelyn, Jane Austen, Rupert Brooke, and John Donne. He edited nine biographies for the esteemed Nonesuch Press. The first was The Poetry and Prose of Blake issued in 1927. His subjects included William Harvey (Fig 3), William Hazlitt, and Thomas Browne. He would seek authors who interested him “especially if they were unfashionable.” His scholarly bibliographies were of more than academic interest; they revived attention and appreciation for these figures. In his presidential address to the Bibliographical Society, he confessed one of his principal motives was hero worship, followed by a search for every biographical detail. In his autobiography The Gates of Memory (Fig 2), he elegantly details his life and works; with undue modesty he saw himself as a collector—a craftsman rather than an original creative thinker.1

As a man, Keynes was gracious and congenial. He remained urbane yet boyish with a ready smile and laugh. His highly erudite tastes were balanced by a natural simplicity. He was a keen mountain climber, carpenter, and gardener. He married Margaret Darwin (1890–1974). Their sons were the physiologist Professor Richard Darwin Keynes FRS, the bibliophile explorer Quentin Keynes, surgeon and historian Milo Keynes MD, and Stephen Keynes; and a daughter Harriet Frances—all were great-grandchildren of Charles Darwin.2

He died aged ninety-five and was buried at St. Mary’s Churchyard, Brinkley (Fig 4). When he died the Keynes name was a household one—principally, though not entirely, because of his elder brother’s (Maynard) eminence as an economist, but also because it had become one of the great Cambridge intellectual dynasties,8 linked partly by marriage and partly by collaboration and friendship with the Darwins, the Adrians, the Huxleys, and the Wedgwoods.

Note

- James Blundell, an obstetrician, first performed human-to-human blood transfusion. In 1901 Karl Landsteiner discovered three human blood groups (O, A, and B).

References

- Keynes G. Gates of Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Keynes_family

- Keynes G. Breast cancer: a case for conservation Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1981; 282(6273): 1392.

- Blalock A (1944) Thymectomy in the treatment of myasthenia gravis: Report of twenty cases. J Thorac Surg 13: 316–339

- Keynes G. The history of myasthenia gravis. Med Hist 1961; 5: 313–326

- Keynes G. Thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Bristol Med Chir J 1949; 66: 100–102

- Pearce JMS. Mary Broadfoot Walker (1888–1974): A Historic Discovery in Myasthenia gravis. Eur Neurol 2005;53:51–53

- Lock SP. Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes. Munk’s Roll 1887-1983 Vol VII. Pg. 319

- Keynes G. Blake: Complete Writings with Variant Readings, editor, Oxford University Press, 1966

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is a retired neurologist and author with a particular interest in the history of science and medicine.

Leave a Reply