Nicolas Roberto Robles

Badajoz, Spain

|

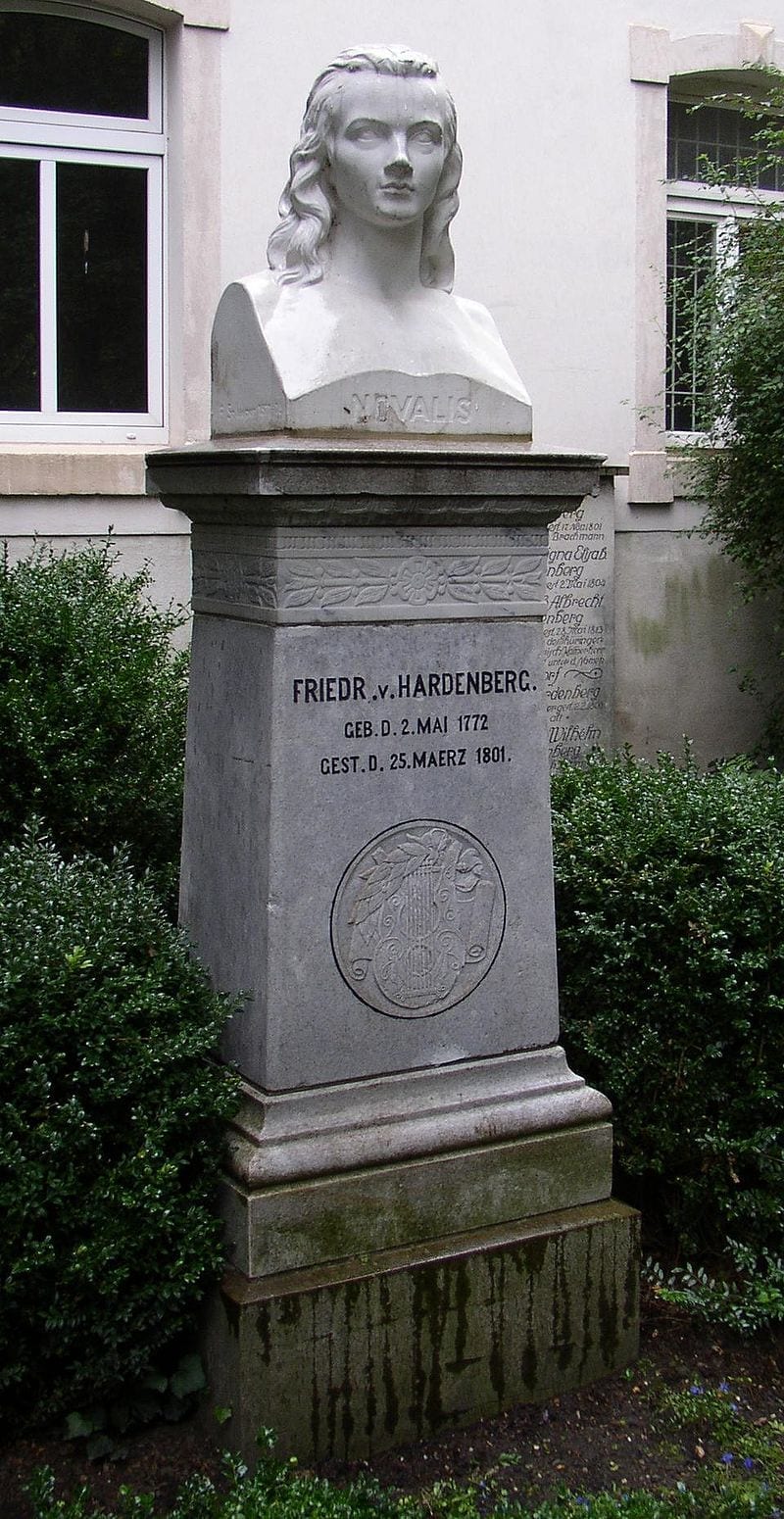

| Figure 1. Bust of Novalis at Nikolaifriedhof (Weiβenfels). Photo by Doris Antony on Wikimedia. CC-BY-SA-2.5. |

Novalis was the pseudonym and pen name of Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr1 von Hardenberg, a poet, author, mystic, and philosopher of early German Romanticism. Young Hardenberg adopted the pen name “Novalis” from his twelfth-century ancestors who named themselves “de Novali” after their settlement Grossenrode, or Magna Novalis (Latin translation for Neubruchland or New Territory).

He was born on May 2, 1772, in the family manor Oberwiederstedt from the second marriage of Heinrich Ulrich Erasmus von Hardenberg with Auguste Bernhardine von Bölzig, who gave birth to eleven children, including their second child, Friedrich. He studied law at the University of Jena (1790), where he became acquainted with Friedrich von Schiller, and then at Leipzig formed a friendship with Friedrich von Schlegel and was introduced to the philosophical ideas of Immanuel Kant and Johann Gottlieb Fichte. He completed his studies at Wittenberg in 1793.

In 1794 he met the young Sophie von Kühn in the nearby Grüningen Castle. He became engaged to her on March 15, 1795, shortly before her thirteenth birthday. She died on March 19, 1797, in agony after an operation on her liver for a possible subphrenic abscess related to pulmonary tuberculosis, in this time called “the white plague.” She was only fifteen years old. Novalis expressed his grief in Hymnen an die Nacht (1800; Hymns to the Night), six prose poems interspersed with verse:

. . . liebliche Sonne der Nacht,

nun wach’ ich

denn ich bin Dein und Mein

du hast die Nacht mir zum Leben verkündet

mich zum Menschen gemacht

zehre mit Geisterglut meinen Leib,

daß ich lustig mit dir inniger mich mische

und dann ewig die Brautnacht währt.

. . . dear Sun of Night,

I awoke then

for I am yours and mine.

You have proclaimed

the night alive to me,

and made me human.

Consume with spirit-ardor my body

that I may mingle with your subtle winds

and ever keep the Bridle Night.

|

| Figure 2. Sophie figures as Novalis’ fiancée in her funerary plate. Text reads: On this graveyard lies Sophie von Kühn * March 17, 1782, † March 19, 1797, at the castle Grüningen, the bride of the poet Friedrich von Hardenberg <NOVALIS>. From Barroso,3 CC-BY-SA-3.0. Image in public domain. |

In 1798 he went to Leipzig to study mineralogy and chemistry and was hosted in the house of the aristocratic von Charpentier family. Only half a year after Sophie’s death, he was secretly engaged to Julie von Charpentier, the daughter of the host, Johann Friedrich von Charpentier, professor and director of the mines.

At the beginning of the summer of 1798, Novalis became severely ill and was diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis. It has been suggested that he was probably infected while taking care of Friedrich Schiller, who was in 1790 a professor of history at the University of Jena. Nonetheless, Novalis worked in saline management and was appointed saline assessor and member of the saline management board in December 1799. In late autumn 1799 he had met other writers of so-called Jena Romanticism after he had made the acquaintance of Ludwig Tieck in July. In 1800 he published Hymns to the Night. On December 6, 1800, the twenty-eight-year-old was appointed Supernumerary Governor for the Thuringian District, even though he was terminally ill with the lung disease that made it impossible for him to practice his profession. On March 25, 1801, Novalis died in Weißenfels of a hemorrhage resulting from Schwindsucht (tuberculosis). He was buried in Weißenfels in the old cemetery.

Recent research suggests that cystic fibrosis may have been the actual cause of death, since Novalis had suffered from pneumonia and general weakness from his childhood. A hereditary disease is also suggested by the deaths of his brother Erasmus and other siblings who died young with similar pathologies.1

At the beginning of the nineteenth century, most Romantics who followed Lichtenberg were convinced that the Cartesian formula “I think, therefore I am” did not reflect the true human condition. The “I” of human consciousness was regarded as being too powerful and autonomous. Novalis recognized the power of the unconscious by issuing the slogan: “Der Weg der Erkenntnis führe nach innen” (The path of knowledge leads inward). In fact, Novalis could be considered as a predecessor of surrealist poetry.

The “Blue flower” (Blaue Blume) was a central symbol of inspiration in Romanticism. Novalis introduced the symbol into the movement through his unfinished coming-of-age story, “Heinrich von Ofterdingen.” After a meeting with a stranger, the young Heinrich dreams about a blue flower, which calls to him and absorbs his attention. It stands for desire, love, and metaphysical striving for the infinite and unreachable:

“Er sah nichts als die blaue Blume, und betrachtete sie lange mit unnennbarer Zärtlichkeit.”

“He saw nothing but the blue flower and gazed at it for a long time with indescribable tenderness.”

A central concern for Novalis was understanding man as both a historical and biological being, and as a “Homo Patiens” who required diagnosis and corresponding therapy. The poet, although not a doctor himself, had a wealth of experience as a chronic patient and, from his perspective, a solid education about sickness and health. He even wished that medicine was part of everyone’s education, postulating that those who process illness sensibly do so through a pronounced sense of individuality, which healthy people lack. He longed for a connection between poetry and science: “Poetry is the great art of construction of transcendental health. So, the poet is the transcendental doctor.”

|

| Figure 3. Nikolaifriedhof (Weiβenfels) in winter. Here is the grave of von Handerberg family. Photo by Jwaller on Wikimedia. CC BY-SA 3.0. |

Zur Hochzeit ruft der Tod

Die Lampen Brennen hellen

Die Jungfrau sind zur Stelle

Um Öl ist keine Not

Erkangle doch die Ferne

Von deinen Zuge schon,

Und ruften uns die Sterne

Mit Menschezung` und Ton

Death summons to the wedding,

The lamps burn brightly

The virgins stand in place

There is not lack of oil

If the distance would only sound

With your procession

And the stars will only call to us

With humans tongues and ton.

— From Hymns to the Night

References

- “Freiherr” means “Baron.”

- Danzer G. “Wer sind wir?: Auf der Suche Nach der Formel des Menschen.” Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, 2011.

- Barroso, Maria Do Sameiro. “Insights on the history of tuberculosis: Novalis and the romantic idealization.” Antropologia Portuguesa 36 (2019): 7-25. doi:10.14195/2182-7982_36_1.

NICOLAS ROBERTO ROBLES is professor of Nephrology at the University of Extremadura.

Summer 2020 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply