James Franklin

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

| Lesser golden-backed woodpecker (Dinopium benghalenese) – Central India (March 2019). Photo by the author. |

|

| Portrait of Leopold von Auenbrugger. Credit: Wellcome Collection. (CC BY 4.0) |

|

| Inventum novum ex percussione… by Leopold von Auenbrugger. Wellcome Images. CC BY 4.0. Via Wikimedia. |

|

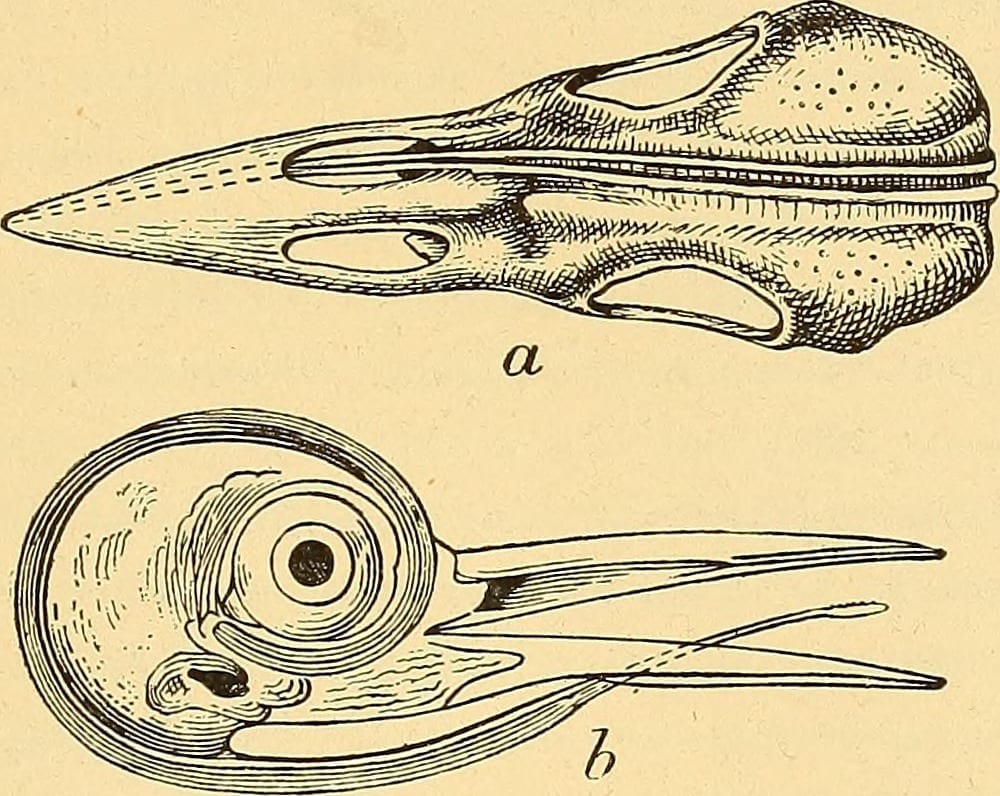

| Anatomy of the woodpecker’s tongue. page 324 of “Annual report” (1902). State of New York Forest, Fish, and Game Commission. Contributed by the Smithsonian Library. Accessed via the Internet Archive. |

In learning the art of physical diagnosis, every medical student is taught the technique and application of percussion. Percussion involves placing the palm and fingers of one hand on the patient and using the tip of the third finger of the other hand as a hammer, striking the distal interphalangeal joint of the hand resting on the patient to elicit both the sound and the sense of resonance or dullness in the structures below. Using this method, the student learns to demarcate the presence and level of an accumulation of fluid in the pleural cavity, a consolidation of a segment of the lung, the size and contour of the heart, the size of the liver, and the presence of an enlarged spleen. Students are taught that the credit for discovering this technique is given to the Austrian physician, Leopold Auenbrugger (1722-1809).1 Tradition has it that Auenbrugger, the son of an innkeeper in Graz, learned about percussion by observing his father tap on wine barrels to determine how full they were. He studied medicine at the Medical School of Vienna under Baron van Swieten and subsequently established a successful private practice in Vienna. He seemed to have a special interest in diseases of the chest and carried out studies on tuberculosis. He described percussion of the chest in a little book first published in 1761 after having studied the technique for a period of seven years. Written in Latin, the 95-page monograph Inventum Novum or “New Discovery” is the first record of the use of percussion as a tool for examining the chest. He investigated the application of his method by injecting fluid into the pleural spaces of cadavers and demonstrated that the presence of effusions could be recognized by percussion. His work was ignored by his close associates at the school of medicine, van Swieten, and his successor Anton de Haen. However, de Haen’s successor, Maximilian Stoll, treated Auenbrugger’s work with more respect, and percussion was taught to students. One of Stoll’s students, Josef Eyerel, wrote a book on Auenbrugger’s percussion methods which came to the attention of Jean-Nicholas Corvisart (1755-1821), Napoleon’s physician.2 In 1808, Corvisart obtained a copy of Auenbrugger’s original monograph and translated it into French, calling the attention of his colleagues and students to the usefulness of the method.3

There is the romantic notion that Auenbrugger’s discovery and his sensitivity to sound and timbre had to have occurred in Vienna, the music capital of Europe. After all, this was the age of Mozart and Haydn. Surgeon and historian Sherwin B. Nuland informs us that Auenbrugger was a skilled musician and a lover of opera.4 Perhaps it was in his genes. His daughter Marianna was a composer and a pianist who studied with both Joseph Haydn and Anton Salieri.

But could it be that woodpeckers, practicing their well-recognized “drumming” behavior, intuitively learned the principle of this technique long before the good Viennese doctor?

It was the middle of a beautiful morning in March 2019 deep in the Pench National Park in Central India, when we spotted the lesser golden-backed woodpecker pictured above darting around and behind the trunk of a eucalyptus tree. As a novice birder, I found myself gasping, “That’s the most beautiful bird I have ever seen!” The lesser golden-backed woodpecker is also known as the black-rumped flameback woodpecker. The bird is widely distributed in the Indian subcontinent. Five subspecies are recognized throughout the subcontinent as well as in Sri Lanka. The lesser golden-backed woodpecker was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758, who gave it its binomial name Picus benghalensis. It now resides in the genus Dinopium where it was placed by the French polymath Constantine Samuel Rafinesque in 1814.

The photograph reveals two remarkable adaptations that allow the woodpecker to stabilize itself vertically on the side of a trunk and rapidly hammer away with its sturdy beak. Woodpeckers, unlike most birds which have three forward toes and one hind toe, have two toes in front and two in back. This arrangement, along with its stiffened tail feathers, allows the bird to firmly situate itself vertically on a tree trunk, lean back, and pound away.5

Not evident in the photograph are a remarkable set of adaptations that serve as shock absorbers to protect the brain while the bird engages in its well-known drumming—which may reach a frequency of 18 to 22 times per second. So much energy is generated in this activity that the brain would overheat if the bird did not intermittently pause. As additional protection, the skull is a matrix of crisscrossing bones that can compress and expand. Unique to the woodpecker is its tongue. The tongue consists of nine thin bones covered with muscle, extending from the floor of the mouth, wrapping around the inside of the skull, and finally attaching at the level of the nostrils. Walter Isaacson pointed out in his biographical study of Leonardo da Vinci an item appearing in one of the artist’s notebooks as part of a to-do list: “Describe the tongue of the woodpecker.”6 It is not known if he ever followed through on his memo. The first good illustration of the tongue of the woodpecker was done by the Dutch anatomist Volcher Colter in 1575.

So impressive are the forces generated by the woodpecker’s activity that mechanical engineers find the analysis of the woodpecker drumming system a worthy avenue of study applicable to the design of shock-absorbing systems.7

The pecking behavior allows the bird to uncover adult insects, their eggs, and larvae under the bark. It also allows them to drill cavities in dead or dying trees for nesting. Woodpeckers also use their hammering technique for communication and to seek out mates. As the woodpecker percusses the trunk of the tree with its beak, it can detect the presence of spaces below the bark.

Alas, no woodpecker ever troubled itself to write an article in a journal or publish a monograph that might substantiate this claim. And so, by the well-known dictum “publish or perish,” Auenbrugger retains his claim to fame.

|

|

| Lesser golden-backed woodpecker (Dinopium benghalenese) – Central India (March 2019). Photos by the author. | |

Footnotes

- George Dunea, Percussion of the Chest: Leopold Auenbrugger, Summer 2018 Hektoen International, https://hekint.org/2018/06/25/percussion-of-the-chest-leopold-auenbrugger/?highlight=Auenbrugger

- George Dunea, Jean Corvisart: Napolean’s physician, Hektoen International, Spring 2013, https://hekint.org/2017/01/27/jean-corvisart-napoleons-physician/?highlight=Corvisart

- Robert G. Rate, Leopold Auenbrugger and “The Inventum Novum,” The Journal of the Kansas Medical Society, January 1966, p. 30-33

- Sherwin B. Nuland, Doctors: The Biography of Medicine, Alfred A Knopf, 1988, p. 204

- Dr. Roger Lederer, Why do Woodpeckers Peck? Ornithology: The Science of Birds, September 30, 2015, http://ornithology.com/why-do-woodpeckers-peck/

- Walter Isaacson, Leonardo Da Vinci, Simon & Schuster, 2017, p. 525

- Sang-Hee Yoon and Sungmin Park, Bioinspiration & Biomimetics, 6: 1- 12, (March) 2011

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 4 – Fall 2020

Summer 2020 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply