Enrique Chaves-Carballo

Kansas City, Kansas, United States

|

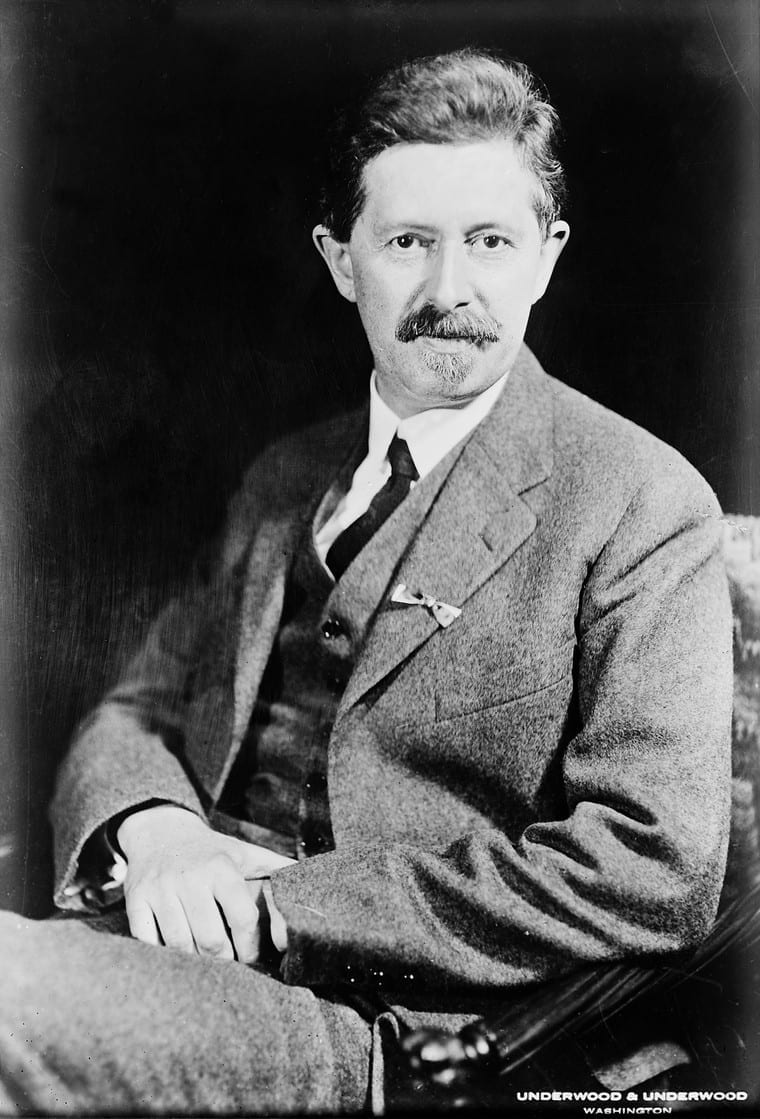

| Samuel Taylor Darling at age 51, portrait by Underwwod & Underwood, 1923. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) |

Samuel Taylor Darling, widely considered as the foremost American tropical parasitologist and pathologist of his time, was born in Harrison, New Jersey on April 6, 1872. He studied medicine at the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Baltimore, graduating in 1903 at the top of his class and earning the First Prize Gold Medal. During his years as a medical student, he assisted Dr. Nathaniel G. Keirle, professor of pathology and medical jurisprudence, as well as director of the Pasteur Rabies Institute at the Baltimore City Hospital, gaining valuable experience in pathology, chemistry, and bacteriology. Following graduation, Darling trained in pathology at various hospitals in Baltimore.1

In 1905, Darling accepted a position to work as an intern at Ancon Hospital in Panama at a salary of $50 per month. Two days after his marriage to Nannyrle Llewellyn, a student nurse from Virginia, Darling left for Panama and joined William Gorgas and his team of doctors and nurses responsible for the sanitation effort that would control malaria and yellow fever and make possible the construction of the Panama Canal.2

Darling’s training in pathology led to his appointment as chief of the Board of Health Laboratories of the Isthmian Canal Commission at a salary of $333.33 per month.3 The laboratories were responsible for supporting the patient services at Ancon Hospital and for the needs of the Engineering Department. In 1907, the laboratories performed 562 autopsies, 3,795 celloidin sections, 738 bacterial cultures, and 146 tissues and neoplasms. In addition, Darling found time to do important research on tropical diseases such as amebiasis, anthrax, bartonellosis, beriberi, bilharziasis, bubonic plague, filariasis, leprosy, malaria, typhoid, pellagra, piroplasmosis, rabies, relapsing fever, sarcosporidiosis, scurvy, trypanosomiasis, typhus, hookworm, and other intestinal parasites. He was the guiding spirit of the Canal Zone Medical Association and its journal, Proceedings of the Canal Zone Medical Association, published 1908-1927.4

Histoplasmosis

Darling performed more than 4,000 autopsies during his ten-year tenure in Panama (1905-1915). On December 7, 1905 (less than a year after his arrival in Panama), Darling discovered a new disease caused by a previously undescribed micro-organism which he named histoplasmosis and Histoplasma capsulatum, respectively.5

Malaria

Although yellow fever was the most feared disease in Panama and was held responsible for the failure of the French in their attempt to build the canal, Gorgas knew that the real enemy was malaria. Despite the elimination of yellow fever on the isthmus by December 1905, the incidence of malaria among canal laborers surpassed that reported during the French excavation years (1881-1889).6 Darling began a systematic study of the mosquitoes in Panama, observing their breeding and feeding habits. By dissecting infected mosquitoes, he was able to identify one of these, Anopheles albimanus, as the main vector for both tertian (vivax) and estivo-autumnal (falciparum) fevers in Panama. Darling thus introduced the concept of “species specific” control, helping to reduce the cost of sanitation and making it more effective. The results of his investigations were published in 1909 as a classic monograph, Studies in Relation to Malaria.6

In a simple experiment, Darling demonstrated, by removing the wings, that the characteristic buzz made by mosquitoes was due to vibration of the proboscis and not the wings. During the ten years he worked in Panama, Darling published more than seventy original articles and became well-known among pathologists, parasitologists, and malariologists who came to visit. “Darling of Panama” and his laboratories became a mecca for students of tropical diseases from all over the world.

Rockefeller Uncinariasis Commission

Following the triumph of sanitation in Panama and the successful completion of the Panama Canal by the Americans, Darling accepted an offer to join the International Board of Health of the Rockefeller Foundation in 1915.7 He was soon appointed to head a commission to study hookworm disease in the Far East. For the next three years, Darling studied the incidence and consequences of hookworm and malaria in Malaya, Java, and Fiji. The final report, consisting of nearly 200 pages and numerous tables and photographs, revolutionized the diagnosis and treatment of hookworm disease.8 Darling introduced the concept of “mass treatment,” in which it was not the complete elimination of the parasite harbored by an infected individual, but the reduction of the parasite burden in a majority of the affected population that was more important. In this manner, the cost and effort of controlling hookworm were reduced advantageously.

Sao Paulo Institute of Hygiene

After returning from the Orient, the International Health Board assigned Darling to establish an Institute of Hygiene in Sao Paulo, Brazil.8 The intent was to develop a school of public health as well as to assist local authorities in the proper application of hygienic measures. Unfortunately, local politics and disputes interfered with the proper realization of the institute’s goals.

Darling’s paralysis

A year before the end of his assignment in Brazil, Darling developed paralysis of his left leg (he was left-handed).1 He departed Sao Paulo immediately for Baltimore and was seen at Johns Hopkins by Walter Dandy, a prominent neurosurgeon, who diagnosed a brain tumor. On November 18, 1920, Darling underwent a craniotomy and a three-ounce tumor was removed from his right parietal lobe. After a period of convalescence in Baltimore, (when he was appointed a fellow by courtesy at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene), he had residual left-sided weakness. He learned to walk with a cane and to write with his non-dominant hand; but, more importantly, his intellectual faculties were unaffected.

Malaria station, Leesburg, Georgia

After he was sufficiently recovered, Darling was sent by the Rockefeller Foundation to establish a Station for Field Studies of Malaria in the southern U.S.11 He chose Leesburg, Georgia as the site for the station, certain that malaria was abundant in that locale. Once again, his knowledge was sought by students, experts, and health officers, who thronged into Leesburg (named Fleasburg by some who complained about the lack of comfortable lodging and palatable food). In a single year, more than forty of these visitors came to learn from Darling, now recognized worldwide as one of the most prominent malariologists in the United States.

Malaria commission, League of Nations

In 1924, Darling was elected president of the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. He was also named in that year honorary fellow of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene—an honor bestowed only to Gorgas and Darling at the time.12

The League of Nations invited Darling to join the Malaria Commission on its tour of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria. Darling accepted enthusiastically. While returning from Palestine to Syria at a site near Beirut, a motor car accident resulted in the death of several passengers, including Darling, on May 21, 1925.13 Darling was fifty-two years old.

Messages of condolence poured into the Rockefeller Foundation from all over the world. Colleagues expressed their respect and admiration for Darling at memorial meetings. The League of Nations established the Darling Prize and Medal with funds by contributions from friends and colleagues. Since then, the Darling Prize and Medal has been awarded to twenty-eight prominent malariologists from twelve different countries in recognition for their work on malaria.12

Among other honors received posthumously by Darling, the Gorgas (Ancon) Hospital medical library was named the “Samuel Taylor Darling Memorial Library” in 1972.12 A Liberty ship, the S.S. Samuel T. Darling, was launched in 1942 as part of the Merchant Marine fleet during World War II.12

Three species have been named to commemorate Darling: a mosquito, Anopheles darlingi, which is the most important vector of malaria in regions of South America; Diplomys darlingi, an arboreal spiny rat found in Panama; and Besnoitia darlingi, a protozoan parasite capable of damaging muscle and other tissues in mammals, including man.13

Andrew Balfour, first director of the London School of Tropical Medicine and president of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, aptly summarized Darling’s career:

“Darling was a brilliant and versatile man, as someone has said, ‘always scientific, careful, imaginative and honest’ . . . He was the outstanding tropical parasitologist and pathologist of the United States, and by his work and character has given a fine example, not only to his countrymen, but to all who are concerned with those problems which he spent his life in trying to solve and in the solving of which he lost it.”14

References

- Baum GL. Samuel Taylor Darling. Cincinnati: Private Edition, 1958, 5.

- Gorgas WC: Sanitation in Panama. New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1915.

- Baum, 10

- Chaves-Carballo E: The Tropical World of Samuel Taylor Darling: Parasites, Pathology and Philanthropy. Sussex Academic Press, Brighton, UK, 2007, 173.

- Ibid, 180.

- Simmons, JS, et al: Malaria in Panama. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1939, 103.

- Darling ST: Studies in Relation to Malaria. Mt. Hope, Canal Zone, 1910.

- Darling ST, Barber MA, Hacker HP: Hookworm and Malaria Research in Malaya, Java, and the Fiji Islands. Report of the Uncinariasis Commission to the Orient, 1915-1917. International Board of Health (Rockefeller Foundation), Publication No. 9, 1920.

- Baum, 18.

- Chaves-Carballo, 119.

- Baum, 21.

- Chaves-Carballo, 193-197.

- Ibid, 147.

- Balfour AC. Some British and American pioneers in tropical medicine and hygiene. Tr Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg 19:189-231, 1925.

ENRIQUE CHAVES-CARBALLO, MD, is a pediatric neurologist and clinical professor emeritus, Department of History and Philosophy of Medicine, Kansas University Medical Center, who received his medical degree from the University of Oklahoma and trained in pediatrics and neurology at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN. His main interest is the medical history of the Panama Canal and he has published articles and books on tropical diseases, yellow fever, malaria, and Darling.

Summer 2020 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply