L. J. Sandlow

George Dunea

Chicago, Illinois, United States

To visit the extensive ruins of Ephesus is to step back into the beginnings of history. The city had been founded by Ionian Greek colonists in the tenth century BC. It prevailed after an early turbulent history and was prospered initially as an independent city-state. After its conquest around 560 BC by King Croesus of Lydia, it remained an important city under successive empires. It was the site of the Temple of Diana, which had been one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. A lunatic arsonist Herostratus burned it down in 356 BC in order to immortalize his name.

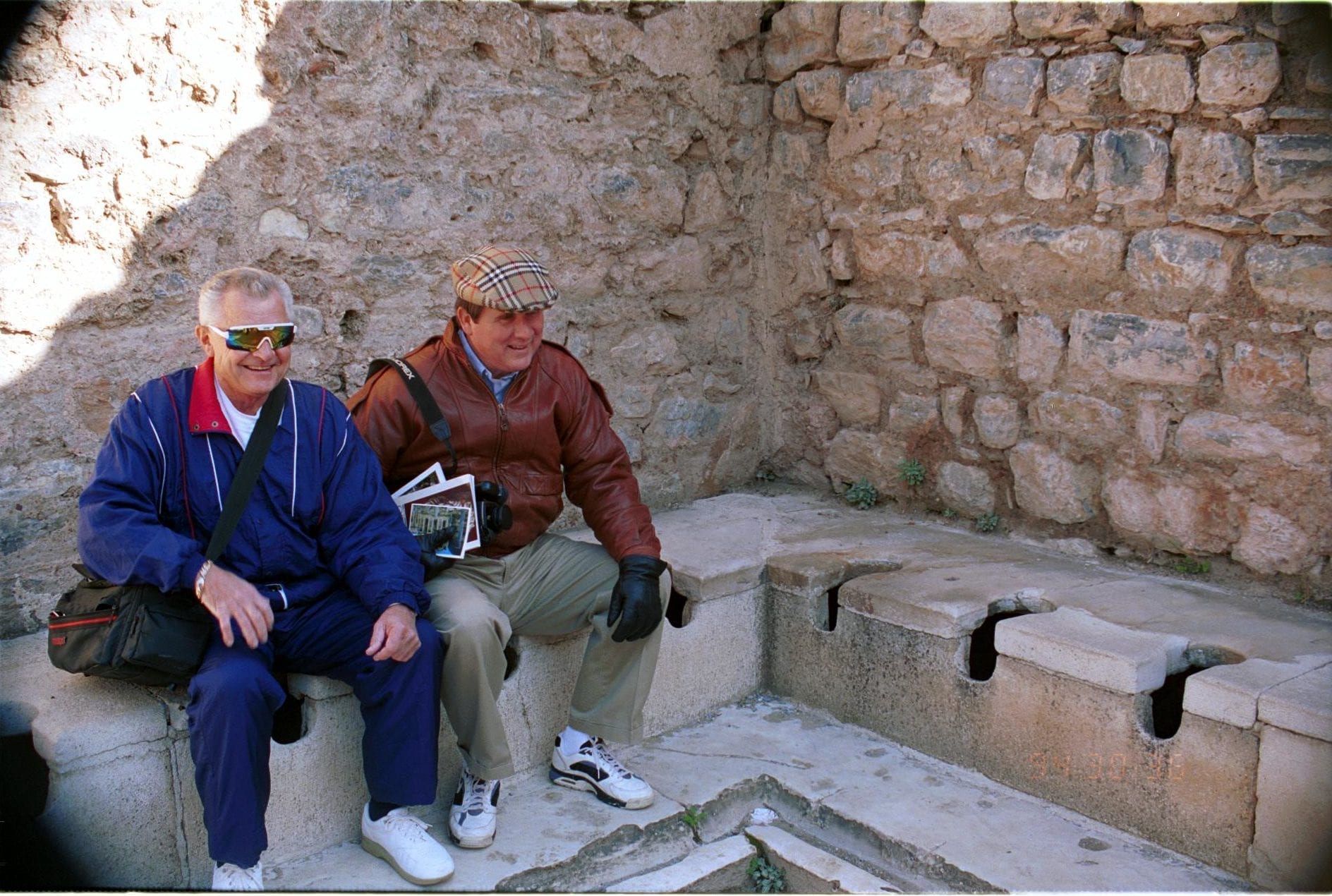

At one time Ephesus had a population of perhaps as many as 150,000 people, two boulevards, and many imposing buildings (figure 1). Medical care and public health were quite advanced. There were temples that also functioned as hospitals, doctors who practiced according to the teachings of Asclepius (figure 2), and even public toilets (figure 3) for which users had to pay a fee.

In Roman time Ephesus became the site of medical schools, and during the reigns of the emperors Trajan and Hadrian (98-138 AD) it gave the world two renowned physicians. The exact dates when they lived is not known, and much of their work has not survived. Both studied medicine in Alexandria, Egypt.

Rufus of Ephesus was to some extent a follower of Hippocrates. He practiced medicine in his hometown and wrote several treatises, including one on the interrogation of the patient that emphasized the importance of the history and of the physical examination. He addressed the subject of gout, which in those days was not well differentiated from other forms of arthritis, and he carried out dissections, but only on monkeys. He wrote on filariasis, plague, jaundice, injuries to the limbs, gonorrhea, and diseases of the kidneys. Addressing the latter, he described renal failure, abscesses, and calculi. To induce a diuresis, he recommended the application of poultices of grilled cicadas, advised flushing the kidneys with large amounts of water, and prescribed urinating in a hot bath to relieve urinary retention.1

Living at the same time as Rufus was Soranus, who also trained in Alexandria but practiced medicine in Rome.2 Many of his writings have also been lost, but he has been honored by having surviving ones plagiarized by later Byzantine and Arab authors. He wrote about fractures, acute and chronic diseases, and also a biography of Hippocrates, but is remembered mainly for his works on obstetrics and gynecology.2 He discussed contraception and abortion, and advised pregnant women to abstain from sexual intercourse and to avoid violent movements after the seventh month. Labor and delivery were to be conducted in an upright posture, with the woman not recumbent but sitting on a stool from which a crescentic area had been cut. He addressed the management of multiple pregnancies, of malpresentations (for which he apparently devised a special maneuver), and outlined the symptoms of postpartum infection. Against the fashion of the time, he opposed the prevailing habit of immersing the newborn baby in cold water. He gave detailed advice on feeding the baby. It was fine, he wrote, to let it cry for a little while because that strengthened its lungs—but if it cried too long it could be because it was hungry, uncomfortable, or constipated.2 Soranus also appears to have written the first account of infantile rickets.

Ephesus continued to flourish in Roman times until the empire itself began to decline. It was sacked by the Goths in 263 AD, and although it was rebuilt it did not regain its former glory. The site was excavated at the end of the nineteenth century and remains a favorite site with tourists and students of ancient history.

|

|

|

References

- Editorial: Rufus of Ephesus. JAMA 1960; 174:2070.

- Dunn PM. Soranus of Ephesus (circa A.D. 98- 138) and perinatal care in Roman times. Archives of Diseases of Childhood 1995; 73:51.

Note

All photographs by L. J. Sandlow

LESLIE J. SANDLOW, MD, is Emeritus Professor of Internal Medicine and Medical Education at the UIC College of Medicine. He was a practicing gastroenterologist and served as Senior Vice President for Academic and Professional Affairs at Michael Reese Hospital. He also served as Senior Associate Dean for Academic and Education Affairs at UIC. He has been active in medical education for over fifty years and developed a continuum of programs in medical education from certificate programs to a doctoral program to prepare educators and physicians for active leadership roles in medical education. He has coordinated the development of an online core curriculum for medical and dental residents which is used at over twenty institutions across the United States.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply