|

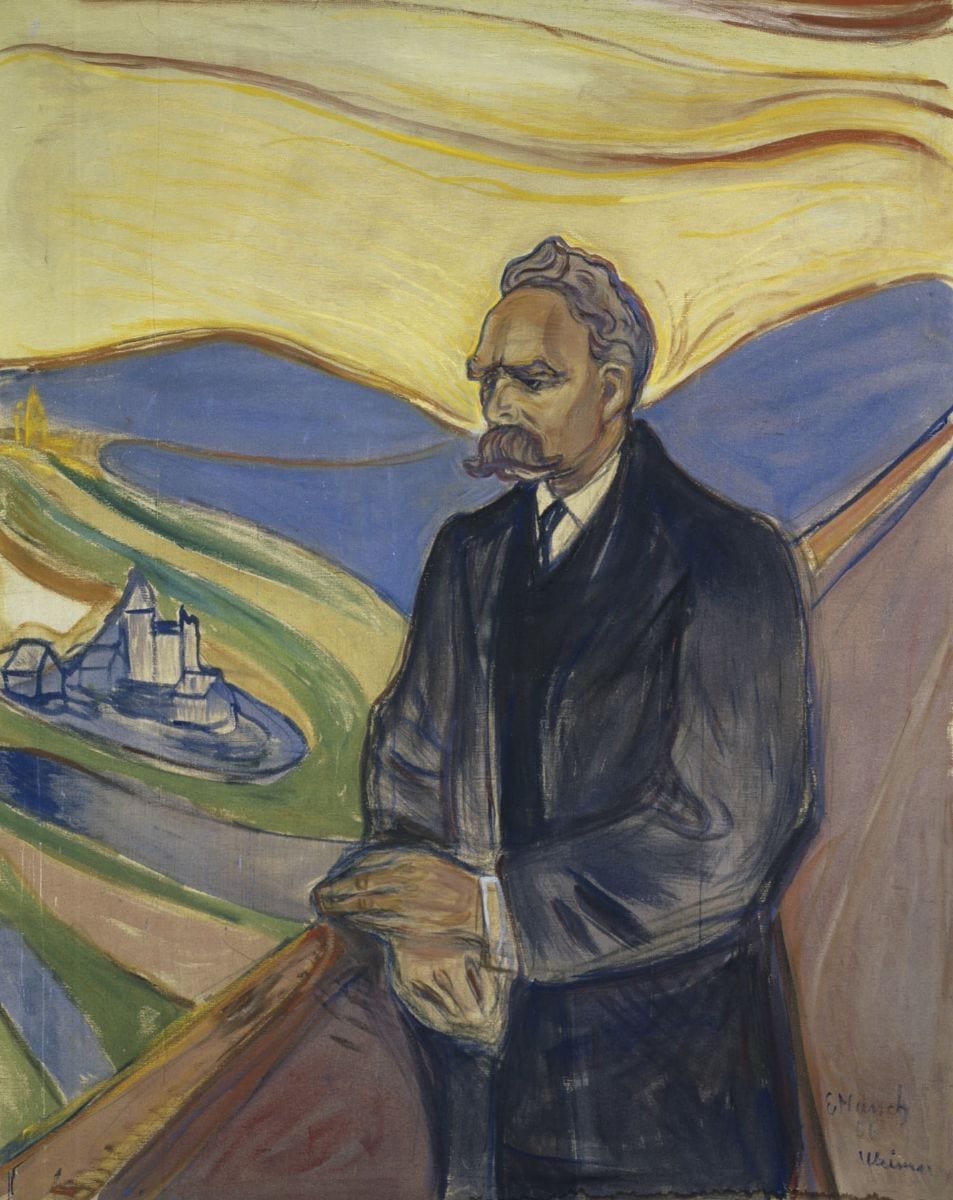

| Friedrich Nietzsche by Edvard Munch. 1906. Thielska Gallerie, Sweden. Via Wikimedia. |

Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the most important philosophers of the nineteenth century. Though often misinterpreted, his influence has been enormous. Like his compatriot Schopenhauer, he questioned the comfortable beliefs of the conservative bourgeoisie of his time. His writings have fascinated generations of readers, his style was exquisite, his ideas original. Bertrand Russell called him an aristocratic anarchist.

Nietzsche admired the Pre-Socratic philosophers and was sympathetic to the teachings of the Buddha. He formulated the concept of the overman or superman, of the eternal recurrence, of a Dionysian life of gaiety and heroism. For Nietzsche, Christianity was a failure because it promoted a slave-like mentality, and when he said God was dead, he meant it was the belief in God that was dead. He asked whether man was a mistake of God or God a mistake of man. He thought that spiritualizing sensuality as love represented a great triumph over Christianity. He despised the bourgeois “herd,” who loved the police more than their neighbor, and advocated a free life as the desirable state for great souls.

In a section of the Twilight of the Idols (1888) titled “Morality for physicians,” Nietzsche proclaimed that the sick man was a parasite of society and that when the meaning of life and the right to live had been lost it was indecent and contemptible for a man to “vegetate in cowardly dependence on physicians and machines.”2 He argued that death should be freely chosen and cheerfully accomplished, amid children and witnesses instead of the “wretched and revolting comedy that Christianity has made of the hour of death.” “Die at the right time,” preached the hero of Thus Spoke Zarathustra (1883) as he came down from the rarefied atmosphere of his mountain bearing his eagle and his serpent. Yet sadly and paradoxically, this was not what happened to him after his collapse in Turin, and he lingered for many years, bedridden and demented.

Nietzsche was born in 1844 near Leipzig in Saxony, Germany. He studied classical philology in Bonn and Leipzig, and at age twenty-four was the youngest person to ever be appointed to the chair of philology at the University of Basel (1869). He resigned from that position in 1879 for health reasons and completed most of his writing in the next decade in Switzerland and Italy. There he lived in increasing isolation, usually in a modest, coldly furnished room, his compositions strewn on the floor, an old trunk holding his only possessions of two shirts and a worn suit, and a tray displaying his numerous bottles of medications: chloral hydrate, opium, and barbiturates. Wrapped in his overcoat, his double glasses close to the paper, he wrote for hours, depressed, in pain, increasingly blind, and isolated.1

We learn from “Nietzsche: in Illness and in Health” by William Gass that Nietzsche had been troubled by ill health most of his life.2 He had hemorrhoids and suffered from “gastric spasms.” He had bad eyesight, often fainted, had fits, and was scared of lightning, which made him hide under the covers. He sometimes vomited blood, for which he was given quinine. He followed prescribed diets seriously, ate only small pieces of meat with Carlsbad fruit salts, but changed his diets and physicians frequently. In the morning he had “his rectum flushed out with cold water.” He was treated with leeches applied to his ears, and these apparently partook of his blood while he partook of his wine.2

Nietzsche had suffered from migraines since he was nine years old. These were recurrent, severe, not preceded by auras, mostly localized to the right side, and often lasted several hours or even days.3 Visual problems began at age twelve, when he complained of tired eyes, and later of diminished vision. Later he was found to be blind in the right eye, and by 1878 he was almost completely blind. Depressive symptoms with suicidal ideas first appeared in 1882, followed by visual hallucinations (1884). The final breakdown occurred in Turin in 1889. There are several versions of this story, the most common being that he saw a man flogging his horse, rushed to him to stop him, collapsed, and was found hanging onto the horse’s neck.

He was taken to a psychiatric clinic or asylum in Basel, where general paresis of the insane, quaternary neurosyphilis, was diagnosed. For the next decade, he remained in a bedridden vegetative state, insane and at times unmanageable. He had a series of strokes leading to impaired speech, facial paresis, and later a left-sided hemiplegia. He was cared for by his proto-fascist sister, who returned from South America and elaborated aspects of his philosophy that he had never expounded. He died in 1900 from pneumonia.

It had long been thought that Nietzsche had suffered from neurosyphilis, general paresis of the insane, but several authorities have now disputed this diagnosis.3-6 Interestingly, the asymmetry of his pupils, an important sign of neurosyphilis, had been noted forty years earlier but was assumed to be a new finding. Other proposed causes of Nietzsche’s disease are meningioma, bipolar affective disorder followed by vascular dementia, a hereditary form of frontotemporal dementia, or mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS), a disease presenting with stroke-like episodes, epilepsy, and neurologic deficits.4,5

In 2008 neurologists from Ghent in Belgium carried out an extensive and meticulous review of original medical notes and other documents, mostly in German, and renewed their opinion that the clinical picture was not consistent with neurosyphilis. Instead, they proposed that Nietzsche had suffered the newly described neurological syndrome of cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy or CADASIL.3 This inherited disease of blood vessels has been found to affect mainly the blood vessels supplying the white matter of the brain. In support of their diagnosis, they pointed out that Nietzsche’s father Ludwig had suffered from an illness running a similar course, with aphasia, multiple strokes, and dementia, becoming incapacitated and dying at age forty-six from “brain softening.” One younger brother also had migraines, suggesting this was a hereditary disease.3

Still, the cause of Nietzsche’s death remains uncertain. It has been suggested that it could be established by an exhumation of the body and DNA testing on tissue and looking for skull imprints that would confirm the presence of a tumor.6 Some authors still favor an atypical form of syphilis as the most likely diagnosis.6 When all is said and done we may never know what killed this remarkable person. But more than a century later people still read him, and academicians argue about what he really meant. And for most of his readers, he remains stimulating, controversial, provocative, and fun to read.

Further reading

- William H Gass. Nietzsche in Illness and in Health, in Life Sentences, Alfred A Knopf, New York, 2012.

- Walter Kaufmann: The Portable Nietzsche. The Viking Press, New York 1954.

- Hemelsoet D, Hemelsoet K, and Devreese D. The neurological illness of Frederic Nietzsche. Acta Neurol Belg 2008; 108:19p.

- Koszka. Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900): a classical case of mitochondrial encephalomyopathy with lactic acidosis and stroke-like episodes (MELAS) syndrome? Journal of Medical Biography 2009: 17(3):161.

- Tényi The madness of Dionysus — six hypotheses on the illness of Nietzsche. Psychiatr Hung. 2012;27(6):420

- Charles André C and Rios. Furious Frederich: Nietzsche’s neurosyphilis diagnosis and new hypotheses. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 2015; vol.73 no.12, São Paulo.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Summer 2020 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply