George Dunea

James L. Franklin

Chicago, Illinois

|

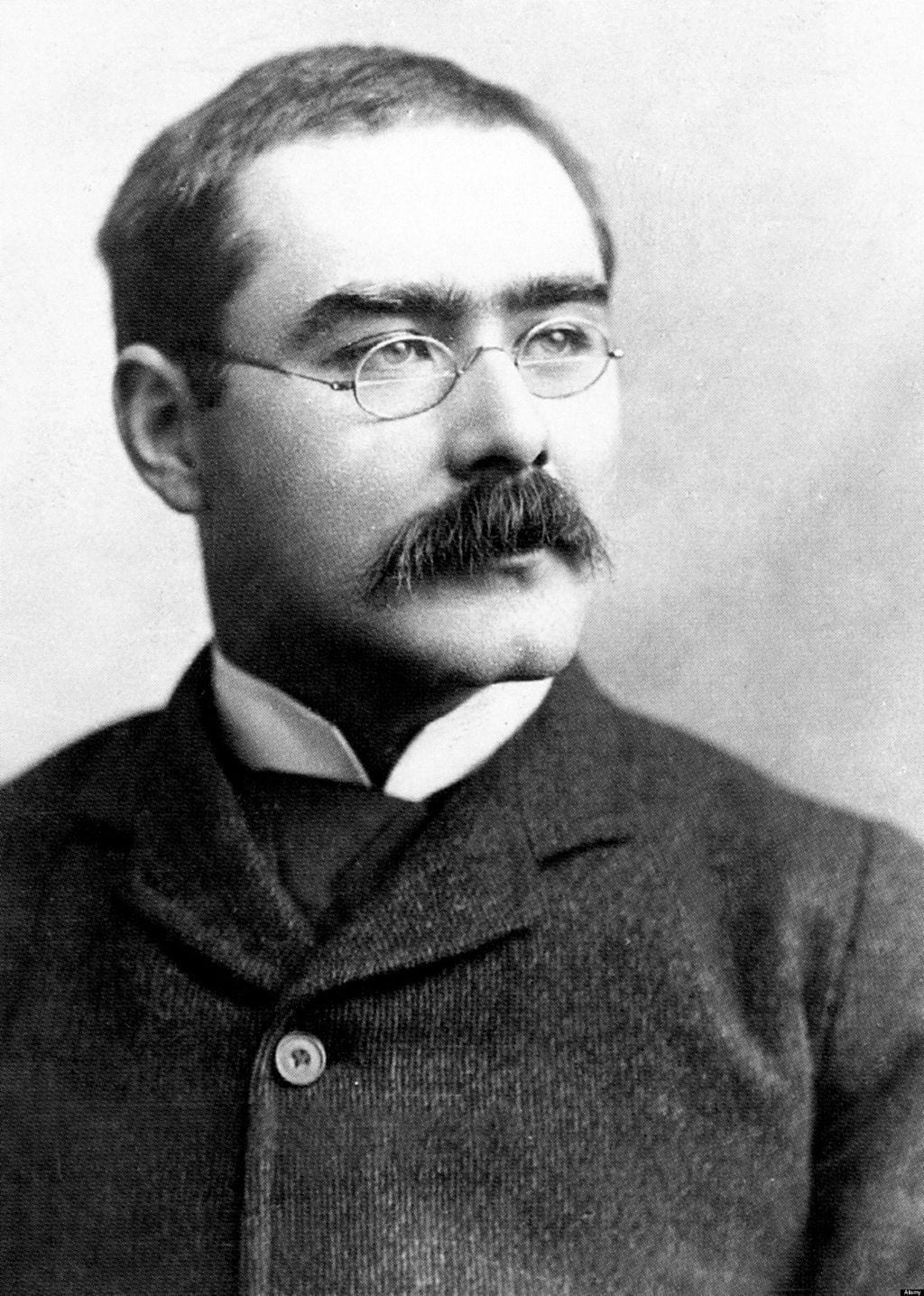

| Portrait of Rudyard Kipling from the biography Rudyard Kipling by John Palmer. 1907. Accessed via Wikimedia |

Born in Bombay but educated in England, the great master of the English language did not return to India until he was seventeen years old in 1882. He worked for local newspapers in Lahore and Allahabad, and in his spare time began to write the many stories that made him famous. Notable were his first set of stories published under the title Plain Tales from the Hills (1888). Kipling’s vivid description of Anglo-Indian and “native” life threw a fresh light on Indian life that enlightened the reading public. He returned to England in 1889 but although he had spent only seven years in India, he was so strongly influenced by that country that his best stories are all set there. With the exception of a four years’ residence in Vermont, he spent the rest of his life in England. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907 but refused a knighthood.

His books have become classics. Who can forget Kim, the English boy looking with his sunburned face like a native, sitting in defiance of municipal orders on the gun Zan-Zammah in Lahore, and involved in the “great game” over Afghanistan between England and Russia. In The cat who walked alone, we learn that dogs are servile but cats proud and self-reliant. In a third-class Indian train with no cushions or food service, we meet The man who would be king, one of the two derelicts planning to go Kafiristan—by their reckoning at “the top the right-hand corner of Afghanistan, not more than three hundred miles from Peshawar.” They convince the native people they are gods and become kings. All goes well until the king wants to take a local girl as his wife. ”Come and kiss me,” he says while sitting on his throne, but she bites him instead, and draws blood—this cannot be a god but clearly is only a man—and the adventure ends up very badly.

Then there are the Jungle Books. Published in two volumes, eight of the fifteen stories are devoted to Mowgli, the naked brown man-cub brought up by the wolves, tutored by Baghera the black panther and Baloo the sleepy brown bear. Rescued from the unmannerly Bandar-log monkeys, he kills his sworn enemy, the tiger Shere Khan, who had kidnapped him from his native village when he was an infant. Mowgli restores Akela as head of the wolf pack and we follow him in a series of adventures as he comes of age. We can also read about a poor Indian about to be hanged for an unspecified crime; and, in Capt. Courageous, a rich young boy falls overboard an ocean liner and is rescued by a crew that impresses him to work and thus teaches him what life is about.

Haters of bureaucracy may find solace in the story of Mr. Hawkins Mumrath of his Majesty’s Bengal Civil Service, ill from enteric fever, given up for lost by two doctors, but recovering and finding to his vexation that the local newspaper has published his obituary. Also vexed are his juniors, who expected to be promoted. Now the government officials want to be reimbursed for the coffin and the brick-lined grave they had purchased for him. Pompously, they have the honor to present him with a bill which he has the honor to refuse to pay, having had the honor not to die. Much paper has the honor to be bandied around from one government agency to another, and Mr. Mumrath at last wins his case but is bitten by a poisonous a rattlesnake hiding in a thicket in the grave.

|

| A poster reading “A new book by Rudyard Kipling. The jungle book.” 1895 – 1911. New York Public Library Digital Collections. |

Kipling’s nostalgia for the Orient becomes evident in his lovely poem “Mandalay,” “where the flying fishes play, and the dawn comes out like thunder out of China cross’t bay.” His hero fantasizes about being shipped somewhere “East of Suez, where the best is like the worst, where there aren’t no Ten Commandments an a man can raise a thirst,” and he is sick of “wasting leather on the gritty pavin’ stones where the blasted English drizzle wakes the fever in his bones.” Indeed, a surprisingly large number of medical personages and medical events appear in his works. They were the subject of a detailed report view by the late William Beatty, a distinguished professor of medical bibliography in Chicago, published almost half a century ago in the now also defunct Practitioner medical journal. More recently they were also reviewed in considerable detail by Dr. D. J Canale of Memphis, Tennessee.

We thus learn from these that as a young man Kipling was troubled with bad eyesight, had a serious attack of tonsillitis in his youth and pneumonia later in life. Having lived in the tropics, he had seen malaria, cholera, and typhoid, and was subject to bouts of malaria and dysentery even after his return to England. In January 1899, Kipling and his family returned to New York to visit their home in Brattleboro, Vermont. By then, in addition to his wife, Carrie, his family had grown to three children. His daughter Josephine, born 1892, a second daughter, Elise, born 1896, and his son John, born in the summer of 1897. When they disembarked in NYC, Kipling and all the children had developed the “flu.” Kipling became gravely ill suffering from pneumonia and for several weeks lay near death. Sadly, his beloved daughter Josephine who at first seemed to be recovering suddenly died. Kipling was so ill at the time that the truth was kept from him until he had sufficiently recovered. Kipling’s fame at the time was such that the course of his illness was carefully followed by the public. The British Medical Journal carried news of his recovery and offered congratulations to the author.

In his works, he mentions several doctors and writes about painful illnesses, medical herbs, anatomy, and dissection. He had a long friendship with Sir William Osler, the Regis Professor of Medicine at Oxford. Kipling later developed epigastric pain from a duodenal ulcer that in those days was difficult to diagnose. His illness was complicated by both bleeding and perforation, he died several days after undergoing surgery in 1936 at age seventy.

In 1908 Kipling was invited to give the commencement speech at the graduation ceremony of the Middlesex Hospital Medical School. Like Susan Sontag, who divided humanity between the kingdom of the well and that of the sick, Kipling divides the world’s population between patients and doctors. Patients, we read, live in fear of the inevitability of their final dissolution and hope the physicians will defer this unwanted moment for as long as possible. Doctors, like kings, are the only ones who will not be given a ticket when stopped by the police for driving over the speed limit. They have the power to tear down entire neighborhoods, impose quarantine, and stop ships from entering the harbor. In return for such privileges, they are expected to work long hours, and be available at a moment’s notice—during the day and in the middle of the night, at the opera or their daughter’s wedding. In his writings Kipling seems to have assumed that all doctors spent their life physically taking care of patients.

|

| Cover for the digital version of Kim by Rudyard Kipling. |

In 1923 on the anniversary of England’s “great surgeon-naturalist,” John Hunter, he was invited to give an address at the Annual Dinner of the Royal College of Surgeons, London. Kipling introduced himself as a “dealer in words.” “Words are, of course, the most powerful drug used by mankind.” He referred to the legend about the god Brahma hiding the ultimate secret of being somewhere in man and it being revealed only when doctors were allowed to look inside the body, in other words to perform dissection; and he thus paid tribute to the work of Andreas Vesalius and also to the anatomists and physicians who followed in his wake.

Kipling’s third medical address, Healing by the Stars, was given in 1928 to the Royal Society of Medicine. He described himself as a “story teller” and told the story of Dr. Culpepper, a seventeenth-century physician-astrologer who derived his information from the stars. From there he was able to deduce that bubonic plague was being transmitted by rats. Also from the stars he got the good news that one of his patients would recover because he suffered only from smallpox and not from bubonic plague.

When all is said and done, no man is without faults, no genius without blemishes. Kipling wrote more than a century ago, in a world where people thought and acted differently. But he remains one of the great writers of the English-speaking world. His works are immortal for their imagination and exquisite language, and their author, deep down, remained nostalgically in love with the “cleaner, greener land” where the flying fishes play, on the road to Mandalay.

References

- Beatty WK. Some medical aspects of Rudyard Kipling. The Practitioner 1975; 215:332.

- Canale DJ. Rudyard Kipling’s medical addresses. J Med Biography 2019; 27:204.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

JAMES L. FRANKLIN, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor emeritus at Rush University Medical Center. He also serves on the editorial board of Hektoen International and as the president of Hektoen’s Society of Medical History & Humanities. He has traveled extensively in Africa and Asia.

Summer 2020 | Sections | Literary Essays

Leave a Reply