John Raffensperger

Fort Meyers, Florida, United States

The author of this delightful book, Dr. John Raffensperger, is a retired surgeon who entered medical school in 1949. His book presents a stark contrast between how medicine was practiced then and how it is now. It highlights the many changes, mostly good but some bad, that have taken place in the sixty-five years since he began to practice.

Dr. Raffensperger recalls his early days in medical school. You had to be smart and be willing to work, but you did not need rich parents. He went to a state medical school, a rather good one, because he could not afford the two more expensive schools in the city. Tuition for one semester was only ninety dollars, but even then most of his classmates had to wait on tables or sweep out labs to make ends meet.

Education in medicine emphasized anatomy. Students spent much time with Gray’s Anatomy, written in 1858 by Henry Gray of St. George’s Hospital in London, who died young from smallpox. His book, now in its forty-first edition, has been remembered over the years with much distaste by generations of students expected to memorize the muscles of the tongue, the relations of the spheno-palatine fossa, and whether the lingual nerve crossed in front or behind the hyoglossus.

The time spent dissecting bodies was an educational exercise that often culminated in the pathologist placing diseased organs on a tray “which was passed from student to student with instructions to touch and feel the syphilitic aorta, lungs oozing pus, or the shaggy deformed heart valves from a patient with rheumatic fever and bacterial endocarditis.” Graduating from Gray’s Anatomy to the more appetizing and much better written textbook of pathology by Professor Boyd from Edinburgh, the students were at last let loose on live patients. The patients in the public hospitals often manifested diseases as advanced as in the days of Laennec and Corvisart, exemplified by the patient who was telling the students that he had a very enlarged “romantic” heart (rheumatic) as well as sifeelis of the brain that he had caught in China.

Medical education was very much a hands-on affair. Students and interns had to become proficient at physical examination, write lengthy histories, establish a good rapport with their patients, and carry out routine blood counts, urinalysis, and sputum smears. The large open wards with little privacy in the inner-city hospitals contrasted starkly with the sleek suburban hospitals where patients enjoyed a pleasant environment and had their own private doctor. The emphasis in education was on developing clinical skills and was as rough as training in the marines. Times were different, and the author remembers when “he balled out interns and nurses, ridiculed lazy medical students, threw faulty instruments across the operating room, and shouted at hospital administrators.” Training to be a doctor was stressful, but it produced experienced doctors who relied on clinical findings rather than on a multitude of ancillary investigations.

We must now fast-forward over Dr. Raffensperger’s interesting surgical career, peppered with astute diagnoses and surgical triumphs. He traveled to Bolivia and to Ecuador, and often used his skills to correct complicated surgical defects. He went to Britain, Switzerland, Canada, France, and Slovakia, also to Cuba and Haiti, finding many deficiencies but also “healthcare systems that were efficient, humane, and less expensive.”

Returning home, and being occasionally a patient, he found that even the simplest complaints could no longer be treated by an experienced general practitioner but required many tests and much money. Doctors no longer had any say in the running of hospitals and administrators had greatly proliferated. Wearing dark suits and carrying clipboards, they spent money like drunken sailors on public relations, feasibility studies, and advertising. The head nurse was now “vice president for nursing” and wasted her time completing reports, while newly graduated residents (hospitalists) with a shift worker mentality provided little continuity in care, spent little time with the patients, but were forever ordering expensive tests. The book closes with a mention of the abuses of medical malpractice and of direct advertising of medicines on television, which only further increases medical costs.

But since the publication of the book, when the chips were down, such as during the Covid-19 outbreak, the administration offices of at least one good size hospital were empty, the door locked. The bureaucrats “worked” from home, the armies of public relations officers, fund raisers, ethicists, patient advocates, and advertisers were nowhere to be seen, and only the doctors and the nurses were present in the hospital. It was rather like in the days when the author of this book first entered medical school.

Reference

John Raffensperger. A Surgeon’s Lessons, Learned and Lost. Strategic Books and Publishing and Rights Co, 2019.

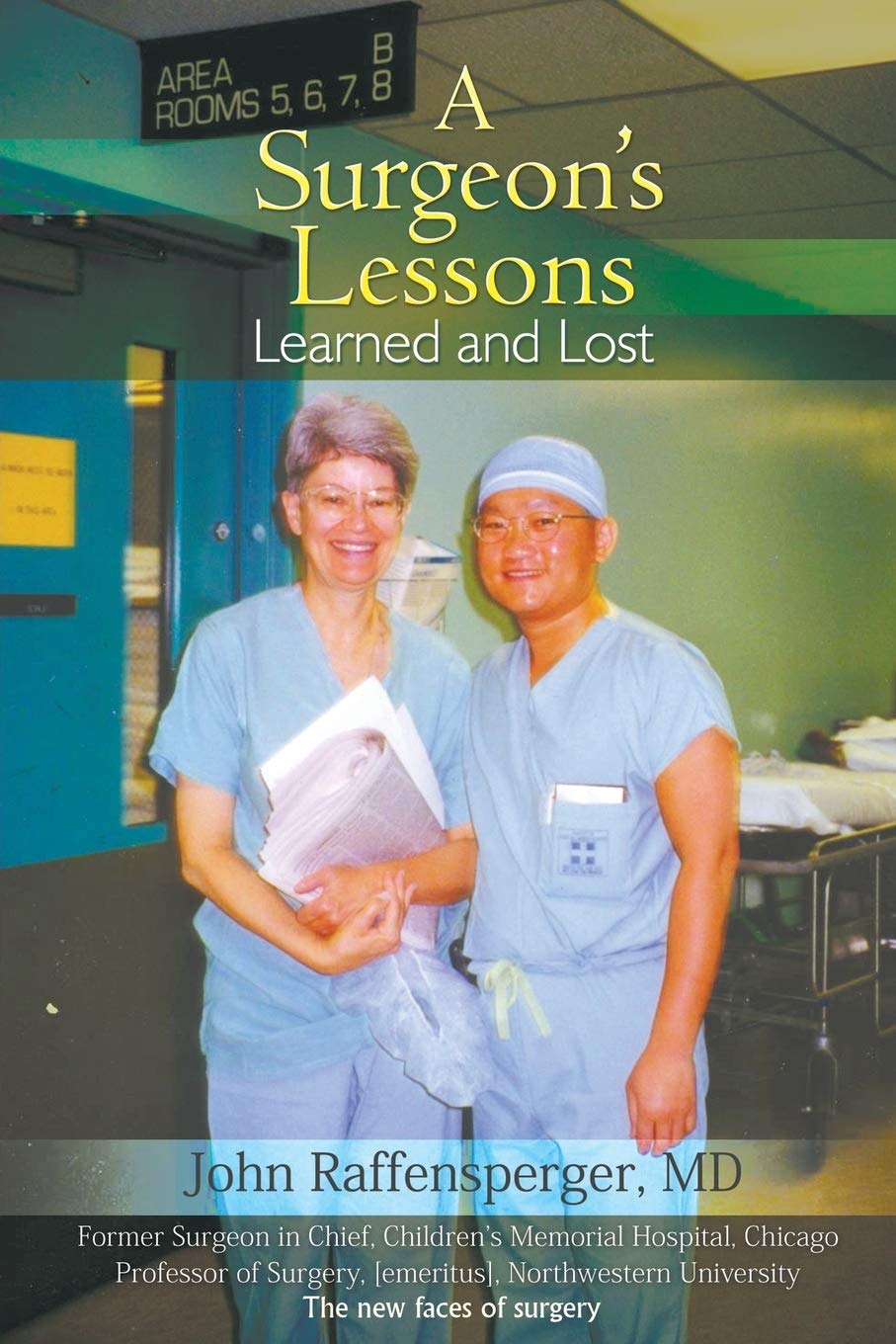

JOHN RAFFENSPERGER, MD, graduated from the University of Illinois College of Medicine in 1953, interned at the Cook County Hospital, spent two years in the Navy, and returned to Cook County for training in general, thoracic, and pediatric surgery. He was on the attending staff at Cook County until 1970, when he went to the Children’s Memorial Hospital and eventually became the surgeon in chief. He has written textbooks, works of medical history, and novels. After retiring from active practice, he sailed across the Atlantic and back, then served as a voluntary pediatric surgeon at Cook County.