Edward McSweegan

Kingston, Rhode Island, United States

|

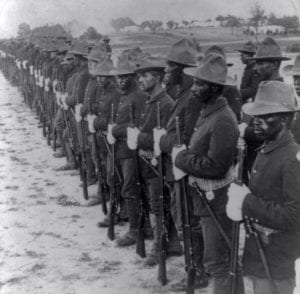

| African American Soldiers in Cuba, 1898, Wikipedia |

In the spring of 1898, the United States rushed into a war with Spain but lacked adequate troops, training, weapons, transport, supplies, food, landing craft, and medical personnel. One deficit that could be corrected before the shooting started was the lack of doctors. George Sternberg, the Army Surgeon General, reported in June 1898 that “one hundred [medical] officers were . . . left for field service, 5 of whom were placed on duty as chief surgeons of Army corps, 36 as brigade surgeons of volunteers, and 59 as regimental surgeons and assistants with the regular troops. The insufficiency of the last-mentioned number was made up by the assignment of medical men under contract.”1

The American Army relied on “contract surgeons” to fill its medical ranks. A contract surgeon was a civilian who wore a uniform. Such a doctor was not enlisted or commissioned but had a contract that could be terminated at any time, even in the middle of a war. The pay was $150 per month and the contract doctor carried the title of “acting assistant surgeon.”2 There was no chance of promotion and no pay if sick or disabled. (Two of the four men on Walter Reed’s yellow fever board in Cuba were contract surgeons.)

“The large number of sick which had to be cared for during the progress of the war . . . rendered imperative the employment of additional medical assistance. Under the provisions of the act approved May 12, 1898, the services of over 650 contract surgeons were engaged.”1 Despite the serious need for additional medical personnel, the contract surgeons were viewed within the Army as being “no better than our common packers or civilian teamsters.”3 To be fair, even the regular Army medical officers were derided by staff and line officers as “nobody but doctors.”4

Army Surgeon General Sternberg also needed African American troops in Cuba and the Philippines because it was “well established” they were immune to yellow fever.2 (They were not.) The Army’s all black regiments (24th and 25th Infantry, and 9th and l0th Cavalry) were deployed from U.S. western territories to Cuba. Later, black National Guard units (8th Illinois, 9th Louisiana, 23rd Kansas) carried out garrison duties in U.S.-occupied Cuba. A small number of the Army’s 650 contract surgeons were African American doctors who cared for these regular black troops (the Buffalo Soldiers) and the black garrison troops.

Sternberg assured African American doctors there was “no discrimination against colored surgeons” in the Army regulations. There was, however, a deep well of social beliefs and practices among white officers and enlisted men that made life difficult for these volunteer doctors. For example, “contract surgeons had the ‘official status of officers’ and by ‘military custom’ associated socially with officers, not enlisted men. But a black surgeon would be a ‘social pariah,’ cut off from the enlisted men of his color and by his color from his fellow officers.”2 It also was believed colored troops “prefer and have greater confidence in the ability of a white surgeon.” Most of the Army’s Hospital Corps personnel were white, so placing a black officer (medical or line) over white enlisted men would be “injurious to discipline.”2 And for white officers and their families, the “attendance of a colored physician would be repugnant.”

This unofficial, unwritten bigotry later would be codified in a 1904 Army Surgeon General memo to the President entitled, “Undesirability of Colored Contract Surgeons.”2 For years afterward, the Surgeon General would publicly maintain there was “nothing either in law or regulation which prohibits the appointment of a colored man in the Medical Corps of the Army, provided he can pass the prescribed physical and professional examination.” But there was a difference between written regulations and daily practices. Hyson’s excellent 1999 article reviewed the lives of five black contract surgeons during the Spanish-American War and the policies and practices they endured.2

|

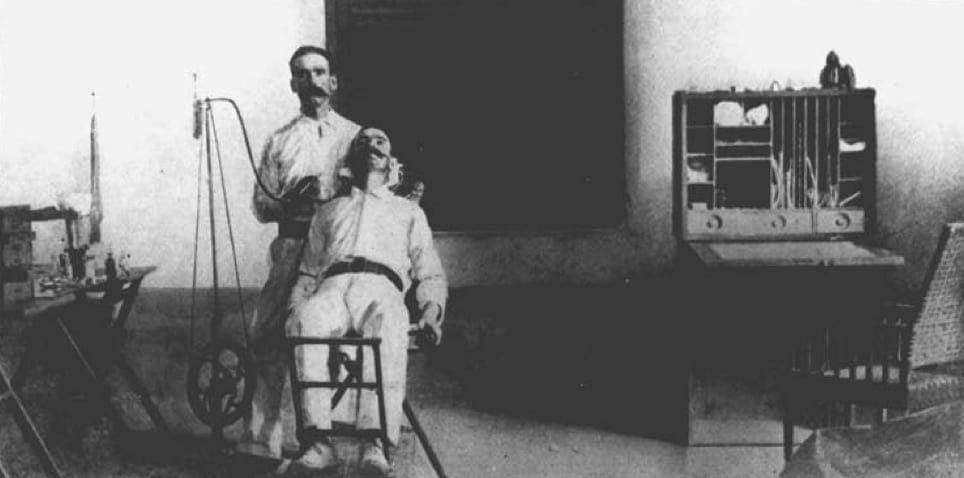

| Surgeon in Cuba, 1898, Library of Congress. Source |

Not until another war in 1917 did the Army Medical Corps change its policy, declaring black physicians were “eligible for appointment in the Medical Reserve Corps on the same basis as white physicians.” 5

The official and unofficial disdain for black contract doctors also extended to black contract dental surgeons. In fact, there were none in the Army when the need for dentists first arose during the 1898 overseas deployment of African American troops.6 When the black 8th Illinois National Guard regiment was sent to Cuba, William T. Jefferson went too. Jefferson was a National Guard line officer, but in civilian life he was a Chicago dentist. Despite routine officer duties in Cuba and a bout of malaria, he found time to provide dental care to some of the black regiments. In that capacity, he may have been the first African American to perform dentistry in the Army.5 “While in the service, seeing the necessity of a dentist, I gave my services free in the hospital to the officers and soldiers of the 8th Illinois, 23rd Kansas and 9th Louisiana, U.S.V.”7

The need for dental care was not limited to African American troops. Nicolas Senn, chief surgeon of the Sixth Army Corps in Cuba wrote in his post-war book that “infection of many oral cavities showed that teeth had been sadly neglected during the campaign. In Cuba and Porto Rico, I saw occasionally a soldier with a tooth-brush under the hat band, but I have reason to believe that most of the tooth brushes were either left at home or thrown away on the march, as unnecessary articles.”8 In Cuba, a soldier suffering with a toothache visited a Cuban dentist “who attempted to extract the tooth but failed to do so successfully. The soldier returned to camp in ‘great agony’ and was found dead the following day from an ‘overdose of morphine.’ The officers believed that the soldier had accidentally overdosed trying to relieve his pain, but the enlisted soldiers claimed he had committed suicide to avoid suffering any longer.”6

In 1901, finally recognizing the medical need for Army dentists, the Surgeon General sought to hire thirty contract dentists.7 Like contract surgeons, the dentists held no rank and wore medical officer uniforms with only the Dental Surgeon “DS” insignia on their shoulders. The first three African American dentists to apply—William Jefferson, Charles Fry, and William Birch—were denied positions. The Surgeon General’s office still was “dodging the issue” of colored doctors and dentists.7 In 1910, an Army Dental Corps of commissioned officers was established. By 1918, the 157,000 African American soldiers caught up in the Great War were being commanded by a thousand African American line officers and 250 “medical and dental reserve corps officers.”2

It is unfortunate that the dentist, William T. Jefferson, left Cuba in 1899. Had he stayed through the end of 1900 he might have presented Major Walter Reed with an interesting choice. On New Year’s Eve in Havana, Reed, having completed his yellow fever studies, wrote to his wife. “Even with a growling tooth I feel cross and ill-natured. All day long my old snag has growled and groaned as if it proposed to take advantage fully of every remaining hour and minute of the 19th Century—I even had to seek relief from the application of Cocaine just before 6 o’clock—this evening—It has about reached the height of its anger, so that I expect to be more comfortable by tomorrow—Out it goes, just as soon as I can reach a dentist—” Would Dr. Reed have approached Dr. Jefferson, or just applied more cocaine until he could find a white dentist?9

|

| Army Contract Dentist, 1898, National Archives and Records Administration. Source |

References

- “Report of the Surgeon-General of the Army to the Secretary of War for the Fiscal Year Ended June 30, 1898.” Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1898. Available at: https://bit.ly/3fDxn7I. Accessed: May 9, 2020.

- Hyson JM. Doctors Five: African-American Contract Surgeons in the Spanish-American War. Mil. Med. 1999;164(6):435-441.

- Gillett MC. The Army Medical Department, 1865-1917. Washington, DC: GPO. 1994, pp. 121. Available at: https://bit.ly/2YU33zX. Accessed: May 12, 2020.

- Cosmas GA. An Army for Empire: The United States Army in the Spanish-American War. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. 1994, Pp 248.

- Hyson JM. African-American Dental Surgeons and the U.S. Army Dental Corps: A Struggle for Acceptance, 1901-1919. U.S. Army, Office of Medical History. Available at: https://bit.ly/2SUwyOe. Accessed: May 10, 2020.

- Hyson, JM, Whitehorne J.W.A., and Greewood JT. A History of Dentistry in the U.S. Army to World War II. Office of The Surgeon General, U.S. Army, Borden Institute, Walter Reed Army Medical Center, Washington, DC, 2008.

- Hyson JM. African-American Dentists in the U.S. Army: The Origins. Mil. Med. 1996; 161(7):375-381.

- Senn N. Medico-Surgical Aspects of the Spanish American War. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association Press. 1900.

- Walter Reed to Emilie Lawrence Reed, Dec. 31, 1900. Philip S. Hench Walter Reed Yellow Fever Collection. Accessed: May 2, 2020. https://at.virginia.edu/35U0krD.

EDWARD MCSWEEGAN, Ph.D., is a microbiologist in Rhode Island. He worked at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and later at the Global Virus Network in Baltimore. He writes about infectious diseases and history.

Spring 2020 | Sections | War & Veterans

Leave a Reply