Kevin R. Loughlin

Boston, Massachusetts, United States

For most Americans, the knowledge of Dwight Eisenhower’s health history is limited to the fact that he had a serious heart attack while president. However, a seemingly casual comment by a non-physician political scientist, Robert E. Gilbert, in his book The Mortal Presidency: Illness and Anguish in the White House, led to a search that revealed a possible, more subtle, explanation for Eisenhower’s vascular disease. In reviewing Eisenhower’s health history, Gilbert mentioned, rather innocuously, that, “For many years, he suffered from transient hypertension, a condition that may have been caused by the small tumor discovered in one of his adrenal glands during his post-mortem in 1969.”1 To some physician readers, this raised the question of whether Eisenhower’s hypertension and vascular disease were explained by an underlying pheochromocytoma.

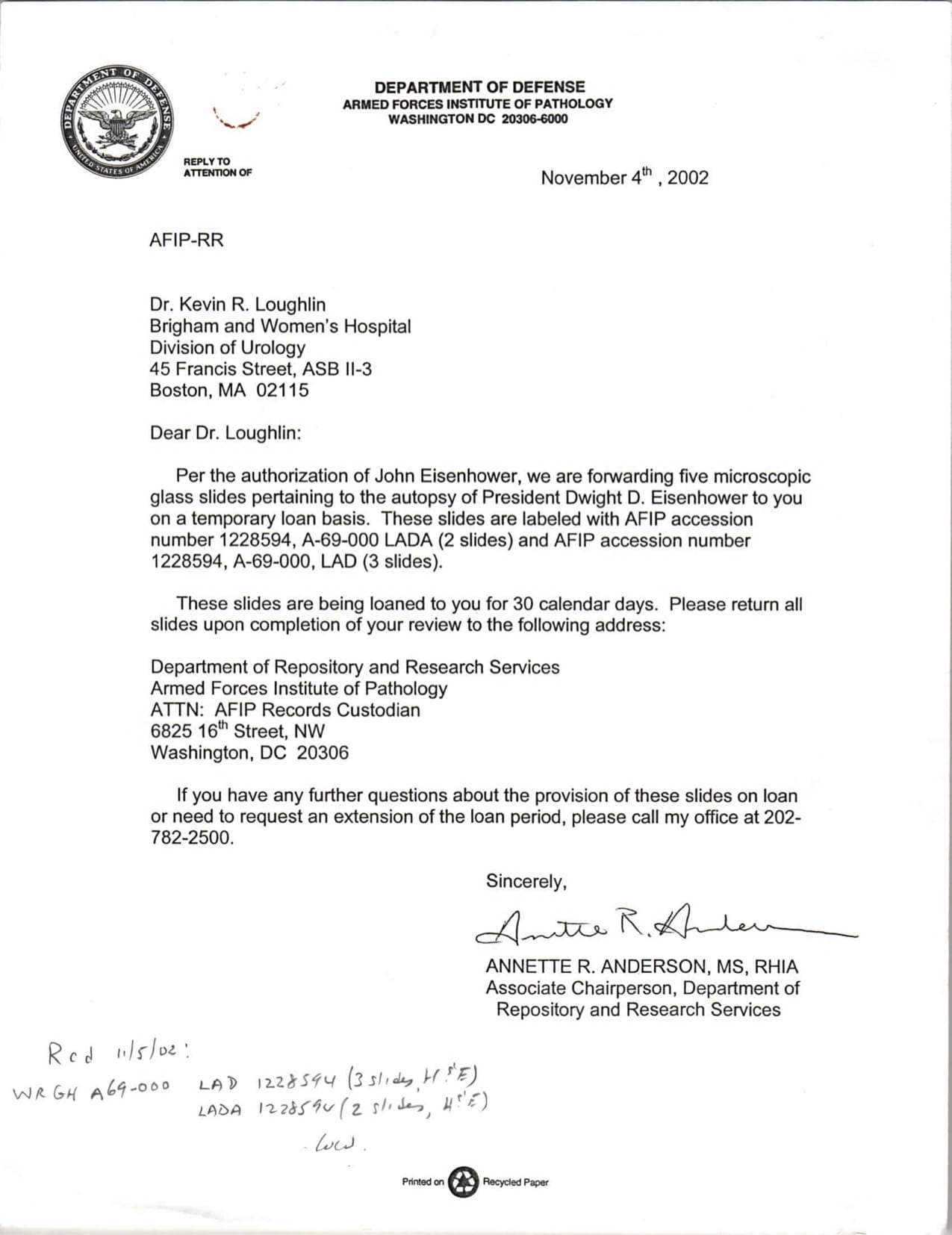

The Eisenhower Library in Abilene, Kansas was contacted for information regarding Eisenhower’s autopsy and suggested the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology might be able to provide the relevant data. The AFIP confirmed they had the autopsy report and pathologic slides, but required a release by President Eisenhower’s son, John Eisenhower, who generously agreed to allow the information to be released. (Figure 1)

The slides were reviewed by a Harvard pathologist, Dr. William Welch, who confirmed the pathologic diagnosis of a 1.5 cm pheochromocytoma in the left adrenal gland. Further investigation into Eisenhower’s health history confirmed hypertension at the time of his well-publicized 1955 heart attack, but revealed that blood pressure elevation may have begun as early as the 1930s when he was in his forties.2

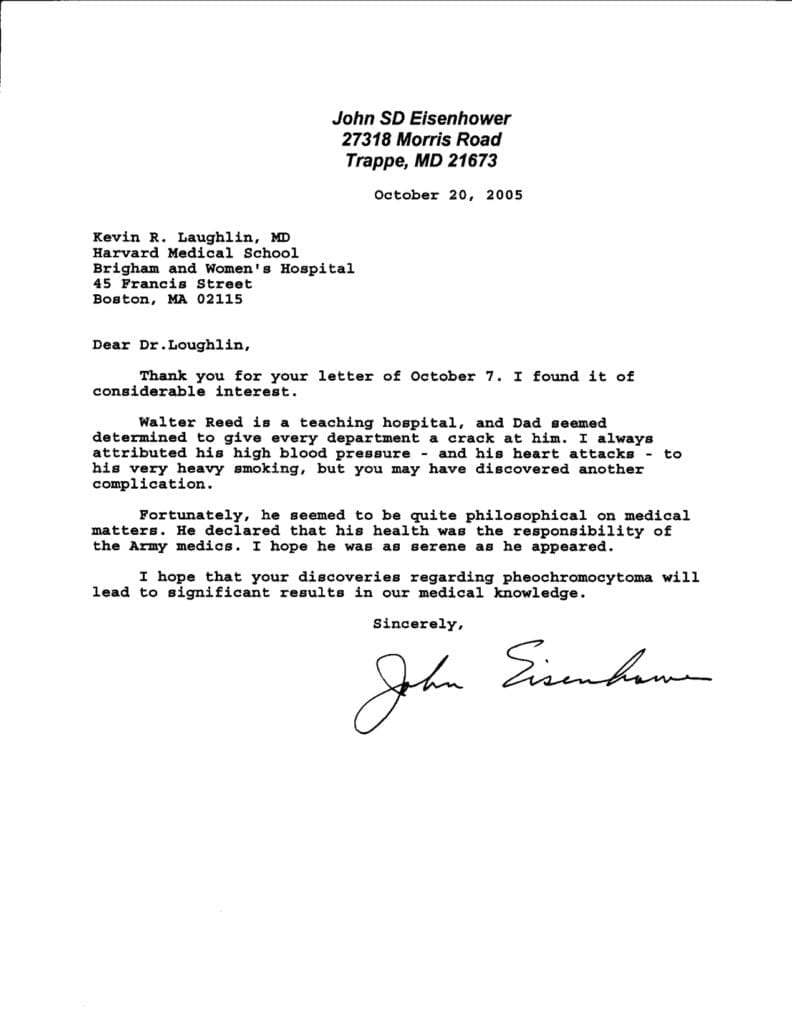

At about this time, an article regarding Eisenhower’s myocardial infarction, “Eisenhower’s Billion-Dollar Heart Attack-50 Years Later” appeared in the New England Journal of Medicine.3 A collaboration transpired among the interested authors resulting in a publication, “The President and the Pheochromocytoma,” which offered the documentation of the pheochromocytoma as a possible explanation for Eisenhower’s extensive vasculopathy.4 President Eisenhower’s son was notified of the findings in the publication and he wrote a gracious reply. (Figure 2)

This narrative serves as the underpinning for a more extensive discussion of President Eisenhower’s health history, raising important issues regarding presidential health which continue to this day.5,6,7 The first documentation of Eisenhower’s health history dates to 1930. When he was forty years old, a reading of 164/94 was recorded in the general dispensary in Washington, D.C. in 1930.2,4 Eisenhower had started smoking as a young officer and always had a hard-driving personality. During the 1930s, he was plagued with intestinal difficulties and continued to have intermittent elevated blood pressure readings.4

However in January 1943, a systolic reading of 168 mmHg was reported by Captain Harry C. Butcher, a naval aid to the general.8 Throughout 1944 and 1945 he received ongoing treatment for hypertension by General A.W. Kenner.9 Throughout World War II, he typically smoked three to four packs of cigarettes per day and was drinking up to fifteen cups of coffee daily.10

His immediate post-war years were consumed as president of Columbia University and, at the request of President Truman, he served as commander of the NATO forces. There is an unsubstantiated report by a retired Army medical officer, Dr. Charles Leedham, that he treated Eisenhower for a heart attack at Oliver General Hospital in Augusta, Georgia in 1949. However, Eisenhower acquiesced to mounting support and political pressure and ran as the Republican nominee for president in 1952.

After his election, his smoking and hard-charging personality continued unabated. He came under the care of an Army physician, General Howard Snyder. On April 16, 1953, he delivered a speech to the American Society of Newspaper Editors. In the course of his remarks, he became diaphoretic and dizzy and almost fainted. This episode was ascribed to food poisoning but may have been a myocardial infarction.

However on September 23, 1955, while visiting Mamie Eisenhower’s family in Denver, he developed “indigestion” while golfing. After initial treatment with antacids, it became clear that he had suffered a significant myocardial infarction (MI). Snyder initially consulted Dr. James Pollock at the Fitzsimons Army Hospital who performed an electrocardiogram and confirmed the diagnosis. Other physicians, notably Dr. Thomas Mattingly, Eisenhower’s personal cardiologist, and Dr. Paul Dudley White from Boston were flown in as consultants. Reacting to the news of the president’s health event, the Dow Jones fell by 6%, its largest single day loss since 1929.3 Mattingly was concerned that the infarct was large enough that a left ventricular aneurysm was present.

Paul Dudley White was already a prominent cardiologist, but he capitalized on these circumstances to advance his own reputation. White’s increased notoriety resulted in a tour of lectures on cardiac disease throughout the nation and he was considered a “rock star” by many of his colleagues.11 Eisenhower would ultimately dismiss him as a “publicity seeker.” However in October of 1955, while speaking at a press conference at the American Heart Association meeting in New Orleans, White enumerated what he considered to be cardiac risk factors, but did not mention hypertension as a risk to be considered.4,12 In retrospect, White may be excused for this omission, as thiazide diuretics only became generally recognized as a treatment for hypertension in the late 1950s. It was not until the completion of the VA Cooperative study (1964-1971) that the relationship between diastolic hypertension and cardiac disease became widely accepted.13

Eisenhower recovered from his cardiac events in Denver, but his health became a factor as to whether he would run for reelection in 1956. In June of 1956, he developed abdominal pain and required surgery on June 9th to relieve an intestinal obstruction due to adhesions from an appendectomy as a young man and Crohn’s disease. Since this occurred in the middle of his reelection campaign, it was emphasized to the public that no malignancy was found.14

As has happened in several presidential elections, health conditions of candidates became political issues. Eisenhower’s cardiac history was an issue throughout the campaign. On election eve, Stevenson gave a speech where he said that medical evidence suggested that Eisenhower was unlikely to serve four more years and that “a Republican victory tomorrow would mean that Richard Nixon would probably be President of this country within the next four years.”15

Eisenhower’s health issues persisted into his second term. On November 25, 1957, he developed a transient inability to speak coherently with slurred speech.16

He underwent medical evaluation and was found to have an occlusion of the middle cerebral artery. Eisenhower’s cardiologist, Dr. Thomas Mattingly, thought that the stroke was likely caused by the stasis of blood in the ventricular aneurysm, and therefore even with anticoagulation the president was at risk for subsequent strokes.

The ongoing cascade of medical issues throughout Eisenhower’s first and second terms caused some of his cabinet members and senior staff to begin to consider contingency provisions in the event of presidential disability. As early as 1955, as a response to the Denver myocardial infarction, Attorney General Herbert Brownell, in concert with Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and presidential chief of staff Sherman Adams, and with Eisenhower’s approval, began to formulate a process in case of presidential disability. This constitutional amendment was proposed by the Brownell Commission and submitted to the appropriate committees in Congress in 1957. However, it was met with considerable opposition by several powerful Congressional leaders including House Speaker Sam Rayburn and Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson, and never got out of committee. However, its major provisions would serve as the scaffold for the 25th Amendment, which was approved in 1967 as a response to the Kennedy assassination.

How long was the pheochromocytoma present in Eisenhower’s left adrenal gland? Is it the explanation for his vasculopathy and subsequent MIs and cerebrovascular accident (CVA)?

These questions can never be answered with certainty. But some reasonable speculations can be offered. Eisenhower had a family history of coronary disease and was a heavy smoker for much of his life as well as occupying stressful positions for most of his lifetime. These are all cardiac risk factors, which alone or in combination could explain Eisenhower’s vascular disease. However, the role of his pheochromocytoma remains an open, tantalizing question. During Eisenhower’s era, there were no catecholamine or other biomarkers available. Abdominal imaging was rudimentary at that time and CT and MRI scans were not available until after his death.

The provocative data reside in the blood pressure readings, available through the Eisenhower Library, which display an episodic hypertension pattern more consistent with an underlying pheochromocytoma rather than a more constant pattern, which would be more consistent with essential hypertension.4,17 His autopsy showed no evidence of metastases, so his was presumably a benign and not a malignant pheochromocytoma.

How long could the pheochromocytoma have been in situ? There is indirect evidence that some pheochromocytomas can have a long natural history. A review of 108 pheochromocytomas in 104 patients by Goldstein et al18 included a recurrent pheochromocytoma that was diagnosed fifteen years after the initial resection.

Medical history is replete with unanswered questions. The etiology of Eisenhower’s health issues is one of such questions. What is certain is that despite a significant MI in 1955, a CVA in 1957, and subsequent cardiac events, he lived for seventy-eight years and helped his country win a war and served a full term as president.

References

- Gilbert RE. The Mortal Presidency: Illness and Anguish in the White House. Basic Books, a Division of Harper Collins Publishers, 1992, p 86

- Gilbert RE. p.80

- Messerli FH, Messerli AW, Luscher TF. Eisenhower’s Billion-Dollar Heart Attack-50 Years Later. New Engl. J. Med. 2005; 353: 1205-1207

- Messerli FH, Loughlin KR, Messerli AW, Welch WR. The President and the Pheochromocytoma. Am. J. Cardiol. 2007; 99(9): 1325-1329

- Loughlin KR. Presidential Health. New Engl. J. Med. 1996; 324(7): 467-468

- Loughlin KR. Presidential Operations. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2009; 209(6): 796-797

- Loughlin KR. A non partisan health checkup for White House candidates. Washington Post 10/10/2019

- Butcher HC. My Three Years With Eisenhower. New York. Simon and Schuster, 1946

- Mattingly TW. Medical history of Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1911-87. General health addendum 5(6). BP determinations as reported from various sources. History given to Col. Lewis in June 1946. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, Kansas

- Bowden M, Ambrose SE(forward) Our Finest Day: D Day-June 6, 1944. Chronicle Books. San Francisco, 2002

- The Heart of a President. Proto: Massachusetts General Hospital/Dispatches From the Frontiers of Medicine, 12/20/2016

- White PD. White links coronary and world peace. The Washington Post and Times Herald 10/30/55 p. E1

- Saklayen MG, Deshpande NV. Timeline of History of Hypertension. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2016;3:3

- Hagerty Papers, box 45. James C. Hagerty’s Press Conferences, June-July 1956. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas

- New York Times, 6 November 1956, p.1

- Eisenhower D D, Waging Peace, 1956-1961; The White House years, Doubleday and Company pp. 227-228

- Mattingly, box 1, General Health, Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library, Abilene, Kansas

- Goldstein RE, O’Neill JA, Holcomb GW et al. Clinical experience over 48 years with pheochromocytoma. Ann. Surg. 1999, 229(6):755

KEVIN R. LOUGHLIN, MD, MBA, was born in New York City and raised on Long Island. He is a retired urological surgeon and a professor emeritus at Harvard Medical School. He enjoys reading medical history and staying informed on current events. He enjoys traveling, at least he did before Covid-19.

Spring 2020

|

|