JMS Pearce

Hull, England, United Kingdom

|

| Fig 1. The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences by Frederick Treves. |

As a specimen of humanity, Merrick was ignoble and repulsive; but the spirit of Merrick, if it can be seen in the form of the living, would assume the figure of an upstanding and heroic man . . .6

The life of Joseph Merrick, also known as “the Elephant Man,” was filled with misfortune and misery which neither family nor society could accommodate. But in his final four years, the distinguished surgeon Sir Frederick Treves befriended him and provided for the first time something like a normal human existence.

Merrick died on the day of this writing, April 11, in 1890, which gives an excuse to revisit an old story, first told to me by my father, who shortly after its publication purchased Treves’ book. (Fig 1)

Joseph Merrick (1862–1889) was born on August 5, 1862, at 50 Lee Street, Leicester to Joseph and Mary Jane Merrick. There were three other children, two of whom died young.1 There is no known family history of his illness.

Apparently a normal baby, at the age of about twenty-one months Joseph developed swelling of his lips, followed by a bony lump on his forehead, which slowly grew. From the age of five, he showed signs of abnormal growths of the skin and bones of his head, trunk, and limbs.2 As a child he fell and injured his left hip, which left him permanently lame. As a youth he found a job at a Messrs Freeman’s cigar shop, but his right hand was too clumsy to roll cigars. Joseph then obtained a hawker’s license to sell gloves door to door, but his elephantine, misshapen features repelled prospective customers.3 After his mother’s death from pneumonia in 1873, his father married Emma Wood Antill, of whom Merrick said: “I never . . . had one moment’s comfort . . . she was the means of making my life a perfect misery.”4 He was so taunted by his stepmother that he would “stay in the streets with a hungry belly rather than return [home] for anything to eat.”

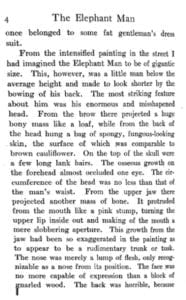

When first examined, his head measured 36 inches (91cm), his right wrist 12 inches (30cm) and one of his fingers 5 inches (13cm) in circumference. Unsightly, irregular lumps and pendulous loose skin (“papillomatous and verrucous”) deformed his face and body. (Fig 2) His speech, swallowing, and facial expressions were all impaired. The left arm appeared normal. His trunk, right leg, and both feet were grossly deformed. He limped cumbrously and had to use a walking stick.5 Treves’ essay gives his first impression. (Fig 3)

|

| Fig 2. Joseph Merrick. No photographer credited in the British Medical Journal article of 1890. Via Wikimedia. Public domain. |

His family could no longer cope and he was in 1879 abandoned in the Leicester Union Workhouse where he remained until 3rd of August 1884. There he would have been subjected to appalling conditions, cruelty, and the scorn of other inhabitants.

Freak shows

After leaving the workhouse, with none of the modern social services existent, the hapless Merrick was forced to eke out a living by displaying his deformities for the music hall proprietors Sam Torr and J. Ellis, and the traveling showman Little George Hitchcock. He soon was transferred to the traveling show in London, run by Tom Norman, whom Treves described as a drunken bully. The telling of the tale was an essential showman’s device explaining bizarre and medically impossible causes for the spectacles shown to the audience. Norman, an accomplished, popular auctioneer and showman was renowned for his ability to tell the tale. Freaks were a common form of Victorian entertainment and there were many similar shows, including Tom Barnum’s famous circus. Amongst many freaks Norman exhibited the world’s ugliest woman, Leonine, the lion-faced lady, and a woman who bit the heads off live rats. Merrick, however, had some words of kindness for the fairground showmen who provided him with a living.

Norman exhibited Merrick in a shop on the Whitechapel Road near to the London Hospital. Whenever he ventured outside he covered himself in a cape and veil to avoid the ill-concealed revulsion of onlookers. Norman, piqued by Treves’ essay in showman’s journal World’s Fair, vehemently challenged his account that demonized him as a “Vampire Showman.” He claimed that the Elephant Man’s longing for independence was realized in the freak show before his “incarceration” at the London Hospital.7

After Norman’s show was closed by the police, Merrick joined Sam Roper’s Fair that visited Brussels where he was robbed. Penniless, he caught the Antwerp–Harwich mail packet and the boat train back to Liverpool Street Station where a policeman rescued him and found Treves’ business card with him. This situation arose earlier when in 1884 Treves had befriended him and gave him his card. He was therefore summoned and took Merrick back to the London Hospital.

It was Reginald Tuckett, a House Surgeon to Frederick Treves, who first discovered Merrick in a freak show close by the London Hospital.2 He informed Treves, who paid a shilling (5p.) to privately visit the show. Puzzled by Merrick’s medical condition and troubled by his plight as the object of public odium, Treves examined him in hospital in 1884. He first showed Joseph Merrick to the Pathological Society of London in 1884.5 He quickly persuaded the hospital director, Frederick Carr Gomm, to launch a public appeal in The Times of 4th December 1886. Within a week sufficient money was raised to create comfortable hospital accommodation where Merrick would remain for the rest of his life, though in bondage to the disnatured torment of deformity. The journal The Hospital in 1887 briefly noted:

|

| Figure 3. Treves’ description.6 |

The “elephant man” is to remain as a permanent inhabitant of the London Hospital. This is in every way satisfactory. The miserable curiosity of a prurient public will thus be deprived of one spectacle at any rate- Let us be thankful for so much.8

Treves, though horrified by his appearance, was impressed by his intelligence and sensitive nature. Joseph read a great deal, made models of famous buildings, and revealingly often quoted Isaac Watts’ lines from “False Greatness”:

Tis true my form is something odd.

But blaming me is blaming God;

Could I create myself anew,

I would not fail in pleasing you.

If I could reach from pole to pole,

Or grasp the ocean with a span,

I would be measured by the soul,

The mind’s the standard of the man.

Interestingly, John Bland-Sutton (1855–1936), an eminent surgeon at the Middlesex Hospital and later President of the Royal College of Surgeons, had also observed Merrick, and noted in his book The Story of a Surgeon:

. . . [There was a] freak museum at a public house The Bell and Mackerel, near the London Hospital. It was on one of these visits in 1884 I saw “on show” opposite the London Hospital a repulsive human being known as the Elephant Man. The poor fellow, John [sic] Merrick—was deformed in body, face, head and limbs. His skin, thick and pendulous, hung in folds and resembled the hide of an elephant—hence his show name.

During his four years in the London Hospital, to cheer him up Treves instigated visits by sympathetic actors and aristocrats—not least Alexandra, Princess of Wales. Public opinion finally was turning against freak shows.

Merrick was found dead in his bed on April 11, 1890. Treves related:

He often said to me that he wished he could lie down to sleep “like other people.” I think on this last night he must, with some determination, have made the experiment. The pillow was soft, and the head, when placed on it, must have fallen backwards and caused a dislocation of the neck. Thus it came about that his death was due to the desire that had dominated his life—the pathetic but hopeless desire to be “like other people.”6 (p.36)

|

| Fig 4. Merrick’s skeleton. BBC/Queen Mary University of London. |

The official cause of death was asphyxia. His body was dissected and his skeleton (Fig 4) preserved as a pathology specimen at the London Hospital. Merrick’s burial place was discovered in 2019 by author Joanne Vigor-Mungovin in the City of London Cemetery near Epping Forest.1 (Fig 5) By remarkable coincidence, she is a distant cousin of Tom Norman.

Diagnosis

The disorder from which Merrick suffered has been much debated. Frederick Treves never suggested a specific diagnosis, although he did not dispute Parkes Weber’s diagnosis of neurofibromatosis (NF1).9 His signs, however, are not consistent with neurofibromatosis.10,11 Currently many regard him as an example of the rare Proteus syndrome.11 Sequencing of his genome might have uncovered the diagnosis, but the skin samples were lost during the Second World War and attempts to extract genetic material from his tooth were unsuccessful.

The Proteus syndrome

The Proteus syndrome is characterized by few or no manifestations at birth. It is not inherited. It usually presents between age six and eighteen months with asymmetrical bony overgrowth.12 Cerebriform nevi (pigmented lesions resembling the brain) on the sole, hand, alae, and ear are frequent and “nearly pathognomonic.” Dysmorphic facial features, capillary malformations, and prominent venous patterning of the skin accompany disfiguring overgrowth of bone and adipose tissues. Deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are often the cause of death. Mutations in the AKT1 gene have been shown.13

A note on Sir Frederick Treves

Frederick Treves (1853–1923) was born in Dorchester, son of an upholsterer. He was educated at the Merchant Taylors’ School. He qualified MRCS in 1875 from the London Hospital and briefly practiced in Wirksworth, Derbyshire. He passed the Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) in 1878. In 1881 he was appointed Erasmus Wilson Professor at the College of Surgeons and lectured “On the Pathology of Scrofulous Affections of Lymphatic Glands.” He became a technically adept and fashionable surgeon and anatomy teacher at the London Hospital, where he became surgeon in Sept 1884 and practiced at No. 6 Wimpole Street. On his return from the Boer War in 1900 he was appointed surgeon extraordinary to Queen Victoria and was made CB and KCVO in 1901.

He was asked to operate for appendicitis, known as perityphlitis, on Edward VII (1841–1910) on 24 June 1902, two days before his coronation. Treves consulted Lord Lister and, despite the King’s reluctance, Treves insisted on surgery. He drained the abscess, leaving the appendix intact. The next day, Edward was sitting up in bed and made an excellent recovery. Treves was given a baronetcy on 24 July 1902. His reputation was sealed; he became the most successful of London surgeons, often receiving the maximum permitted 100-guinea fee. Private patients were so plentiful that in 1898, at the age of forty-five, he resigned his post at the London Hospital.

|

| Fig 5. In memoriam: Joseph Merrick. Bryan Bordelon, Findagrave.com. |

Frederick Treves had a great love of natural beauty, he was an admirable conversationalist, and a stimulating companion who delighted friends with his many anecdotes. He was an accomplished writer, if at times prone to romanticism. His books included The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (Fig 1) (1923), Surgically Applied Anatomy (1883), A System of Surgery (2 vols., 1895), Highways and Byways in Dorset (1906), The Student’s Handbook of Surgical Operations (1892), The Land That is Desolate, and The Cradle of the Deep (1908).

He retired in 1920 to France and then to Vevey in Switzerland. He died of peritonitis complicating cholecystitis, when aged seventy. His funeral took place at St. Peter’s Church, Dorchester, on 2 January 1924, and was attended by the King’s physician, Lord Dawson, and by his literary friend Thomas Hardy. His wife Anne Elizabeth, and his elder daughter Enid Margery survived him.

A play, The Elephant Man by Bernard Pomerance, appeared in 1979. A film was released in 1980, directed by David Lynch, with John Hurt’s brilliant portrayal of Merrick and Anthony Hopkins as Frederick Treves. Somewhat unfairly Treves is portrayed as the hero, Norman as the villain.

What fearsome fate would have befallen the beleaguered Joseph Merrick had it not been for Treves’ humane intervention can only be guessed.

References

- Vigor-Mungovin J. Joseph: The Life, Times and Place of the Elephant Man. London: Mango Books, 2016.

- Howell M, Ford P. The True History of the Elephant Man. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1980.

- Ferguson C. Elephant talk: language and enfranchisement in the Merrick case, in M Tromp (ed), Victorian Freaks: The Social Context of Freakery in Britain Colombus OH: Ohio State University Press, 2008.

- Merrick, The Life and Adventures of Joseph Carey Merrick. Autobiographical pamphlet displayed at his freak shows.

- Treves F. A case of congenital deformity. Trans Path Soc London 1885;36:494-8.

- Treves F. The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences. London: Star Books, 1980, originally published London: Cassell and Company, 1923.

- Norman T. The Elephant Man. Some Facts, World’s Fair, 24 February 1923, no 963.

- Notes and News. The Hospital, 1(16), 264–268 on Jan 15, 1887.

- Parkes Weber F. Cutaneous pigmentation as an incomplete form of Recklinghausen’s disease. Br J Dermatology 1909;21:49-51.

- Seward G R. The Proteus syndrome: The Elephant Man diagnosed. (Correspondence) Br Med J 1986;293:1435.

- Tibbles J A R, Cohen Jr M M. The Proteus syndrome: the Elephant Man Diagnosed. Br Med J 1986;293:683-685.

- Wiedemann H-R, Burgio G R, Aldenhoff P, Kunze J, Kaufmann H J, Schirg E. The Proteus syndrome: partial gigantism of the hands and/or feet, nevi, hemihypertrophy, subcutaneous tumors, macrocephaly or other skull anomalies and possible accelerated growth and visceral affections Europ J Pediat. 1983;140: 5-12.

- Lindhurst JM, et al. A mosaic activating mutation in AKT1 associated with the Proteus syndrome. NEJM, 2011;365 (7): 611-619.

JMS PEARCE, MD, FRCP, is emeritus consultant neurologist in the Department of Neurology at the Hull Royal Infirmary, England.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 3 – Summer 2020

Spring 2020 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply