Roger Ruiz Moral

Universidad Francisco de Vitoria. Madrid, Spain

|

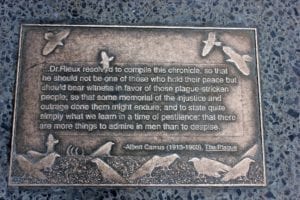

| Quote from the English version of The Plague by Albert Camus in the Library Walk (New York City). Accessed via Wikimedia. Sculpture by Gregg LeFevre. Photo by Heike Huslage-Koch/Lesekreis. |

“I imagine then what the plague must be for you.

Yes, – said Rieux – an endless defeat.”1

The COVID-19 lockdown is today in its fifth week. In my country, Spain, these measures have been especially severe. I am confined to my house despite being a physician, since at this moment I have no practice, while my two sons and my wife, also physicians, are undertaking their clinical activities at their respective hospitals. Every day at 8 pm I hear the applause dedicated to doctors and health workers for their extraordinary efforts in this crisis. So far, the neighborhood has not missed a single day.

However, I have not applauded. I am not sure the applause even convinces me of anything. Instead, I have an uneasy feeling when I hear the news broadcast: “our physicians, those heroes,” and “they risk their lives for us.” Every evening as I hear cheers and applause from the balconies. I wonder if I have the right to feel indifference, bordering on condescension. That is why I asked my wife how the applause makes her feel. Ambivalence, she responds, they are really screams of despair. Sometimes she is moved, but more often the feeling is neutral. This still did not reassure me completely. Then I reread Albert Camus’ work The Plague,1 and it helped me to clarify some of my thoughts and feelings.

In an extraordinary situation like the one we are living through now, with an absolute loss of routine and normality, doctors may be extolled as “heroes.” This enthusiasm is understandable in a situation where people feel helpless. In The Plague, however, Albert Camus offers an extraordinary and nuanced reflection on what it means to be a physician. The dramatic environment of an epidemic makes this easy. The ideas and actions of the main character, Dr. Bernard Rieux, are especially enlightening: “. . . this work can be deadly, you know that well,” the good Rieux tells Tarrou about the work of health providers. Rieux resigns himself to this and strives every day in his work with his patients, with his friends and acquaintances, and in collaborating with the authorities. Throughout the work Camus depicts his character as tireless but simple, assuming his role within the epidemic in an absolutely natural way and understanding almost everyone around him, even with their individual desires and contradictions, from the tragicomic Cottard to the escapist Lambert. Tarrou is surprised at this and asks him: “Why do you put such dedication into it if you don’t believe in God?” Rieux offers Tarrou the personal notion he has of his trade, in which he believes he is on the path of truth, fighting against creation as it is.

Like citizens in today’s pandemic, Tarrou in the plagued city of Oran thinks that doctors do what they do because they are proud, and for this reason they are heroes. Rieux, though, insists: “. . . I don’t know what is waiting for me, what will come after all this. At the moment there are some sick people who must be treated.” I think that the majority of doctors are like Rieux: they do not think too much about what they do. In modern academic and professional discussions, the importance of faithfulness to medicine as a vocation is stressed more and more. But it is a forced ethic. I have serious doubts about the role of a supposed vocation in actual clinical practice. Many students declare that they have chosen medicine as a career because they want to help people. If as a student I had been asked why I had chosen medicine, I would no doubt have answered the same, although the truth is that I really did not know the reason. I think, like Rieux, that I entered medicine indolently, rather than purposefully: “. . . when I got into this job I did it a bit abstractly, in a way because I needed it, because it was a situation like any other, one of those that young people choose.”

But my physician colleagues, including my wife and my children, are currently going to work without necessary protection and with an unacceptable level of uncertainty. They continue working through a sense of duty and professional honesty, because it is the only thing they can do, just as the health providers did in the plague of Oran: “they knew that it was the only thing that remained and not deciding to do so would have been incredible.” As doctors progress in their profession, if they are authentic they must face the truth of the ailments they treat. “When you see misery and the suffering it entails, you have to be blind or cowardly to resign yourself to the plague.” When disease appears, the doctor knows to simply “prevent as many men as possible from dying and to suffer the final separation.” As Camus says later, “for this there is only one way: to combat the plague. This truth was not admirable: it was only consistent.”

In extreme situations like the one we are living through today, it is not only healthcare providers who deserve applause. It is also the men and women who carry out “small” jobs: the supermarket delivery boy who brings our groceries home, the garbage man that collects our waste every night, the sound technician at the radio station that accompanies us in our solitude, the cleaner, the cashier, those “torn and demanding hearts that the plague made of fellow citizens of us all.” Those who like Grand, the apparently gray man in the time before the epidemic, have also not been astonished at the extraordinariness of carrying out their work.

Therefore, physicians are not be congratulated for doing something extraordinary during this time of plague: they are doing what they do because there is no other way. Camus says this kind of praise would be like “congratulating the teacher for teaching that two plus two equals four.” If anything, let us congratulate them instead for choosing such a beautiful profession. Doctors, and the rest of the good-willed men and women from other professions who have chosen to do their work in times of plague, are united by that good will and a sense of honor. It is true that clinicians risk their lives more than many others and for that they are applauded. However, it is also true that “there is always a moment in history in which whoever dares to say that two and two are four is condemned to death.”

In times such as these, we hold up models for admiration in the hope that they will give us strength, help us to advance our cause, and inspire the next generation. By calling them heroes we create a possible mythology about who we are, and about what we can and should do to overcome difficulties. Because this word generates ambivalent feelings in me, these words by the plague chronicler have been especially comforting:

“. . . and if it is absolutely necessary that there be a hero in this story, the chronicler proposes precisely this insignificant and blurred hero, who had only a little kindness in his heart and an apparently ridiculous ideal. This will give truth what belongs to it, the sum of two and two the total of four, and heroism the secondary place. . . . This will also give this chronicle its true character, which must be that of a story made with good feelings, which are neither ostensibly bad, nor exalted in the awkward way of a show.”

The plague disappeared in Oran, as COVID-19 will also disappear. The story ends with the revelation of its chronicler, who is none other than Dr. Bernard Rieux himself, a man who just seemed to do his job, and the confirmation of his torn reality. In his heart a quiet anguish prevailed, the desire to be at the side of his sick wife who was outside the city, “but I knew that this was no longer possible.” In this masterful way, Camus enters the soul of everyone, not only physicians.

“This chronicle cannot be the story of the definitive victory. It cannot be more than the testimony of what had to be done and that without a doubt should continue to be done against terror and its indefatigable weapon; all the men who, unable to be saints, refuse to admit the plagues and strive, however, ‘just’ to be physicians.”

References

- Camus, A. La Peste. Paris: Gallimard (Folio 42), 1972.

ROGER RUIZ MORAL, MD, PhD. Family physician (1987). Associate Professor of Medicine, Head of Medical Education Unit (University “Francisco de Vitoria”, Madrid). Chief-Editor of “Doctutor: Bulletin of Medical Education” (www.doctutor.es). Clinical practice in emergencies and primary care. More than 150 scientific published works. Scientific Books: “The CICCA Model for Communication Skills” (Barcelona, 2004), “Medical Education for Faculties” (Madrid, 2010); “Clinical Communication: Principles & Skills for Practice” (Madrid 2014). Andalusia Award from the Ministry of Health in Research (2002) National “Mati Ezquerra” Award for excellence in Residency Training (2017) and Award of Spanish Society of Family Medicine for education in family medicine (2018).

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 3 – Summer 2020

Leave a Reply