Anne Jacobson

Oak Park, Illinois, United States

|

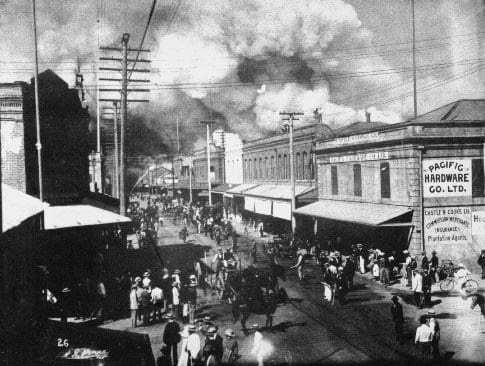

| Figure 1. Honolulu Chinatown fire of 1900. Hawaii State Archives. |

It was a calm, clear January morning on the gritty streets of paradise. Honolulu, the capital of the newly-annexed U.S. territory of Hawaii, was ushering out a century of upheaval that had included the arrival of explorers, missionaries, and deadly diseases such as smallpox and measles; the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy by American colonists; and the arrival of thousands of Chinese and Japanese laborers who came to the islands to work on sugar plantations. The dawn of the twentieth century had offered no relief from the ethnic, political, and economic tensions of the city, but instead had escalated the festering fear and xenophobia of its citizens with the arrival of an ancient scourge: bubonic plague.

In the late 1800s, plague had been killing thousands of people in India, China, and southeast Asia. Because trade was thriving between Asia, the Hawaiian archipelago, and North America, all ships docking in Honolulu’s harbor received a basic inspection of passengers and cargo. In June 1899 the Nippon Maru arrived in port, carrying goods and supplies and at least one dead passenger. The ship’s doctor had diagnosed uremia, but the three-physician team of Honolulu’s board of health—Nathaniel Emerson, Francis Day, and Clifford Wood —examined the body and were highly suspicious of bubonic plague. The ship was quarantined for seven days, the board of health would soon be granted unprecedented authority over citizens in the months to come, and the infected rats that had been living on the ship would escape and make their home in the section of town closest to the harbor: Chinatown.1

For people living in places where plague epidemics had come in swift, deadly waves, it was common knowledge that an excess of dead rats preceded and predicted a multitude of dead people.2 While leading scientists such as Alexandre Yersin and Kitasato Shibasaburo, armed with the burgeoning knowledge of bacteriology in the last decades of the nineteenth century, had discovered the causative bacteria for plague and an anti-plague serum was in development, the method of transmission was still in question. Even as the correlation between dead rats and dead people had been observed for centuries, many leading scientists believed that both rats and people acquired the bacteria by eating infected food or breathing the dust of contaminated soil.3 Paul-Louis Simond, a Pasteur Institute-trained physician-researcher with years of experience studying epidemics around the world, had demonstrated in 1898 that the vector of plague transmission was in fact a bite from the flea living on the rat, but no one in the medical or scientific community took his observations or experimental results seriously until years later.4

Instead, the accepted belief was that plague resulted from filth, and filth was a pejorative commonly applied to the Asian immigrants who had come to work in the United States and its territories in the latter half of the nineteenth century.5 Indeed, the areas known as Chinatown in cities such as Honolulu and San Francisco, suffered from overcrowding, crumbling buildings, open sewage, and heaps of garbage, a situation arising from the intersection of largely absent landlords, neglected infrastructure at the municipal and state levels, and the racist attitudes of white citizens who wished to keep Asian communities confined within a particular area. Clifford Wood, the president of the powerful health board, testified before a congressional committee that the residents of Chinatown “wallowed in [filth] as only Asiatics can and live.”6 It was also a commonly held belief among those of European descent that plague would not affect them because of their superior genetics, hygiene, and diet. When the first deaths occurred in Honolulu’s Chinatown in December 1899, one woman assured her mainland friends in a letter that she was not afraid because plague “seldom attacks clean white people.”7

The early weeks of 1900 had resulted in more deaths, a quarantine of homes and businesses in Chinatown (excluding the adjacent white-owned businesses and residences), daily invasive home inspections by health officials accompanied by police, and finally the selective burning of buildings where plague victims had lived and worked. At the time, fire was believed to be the only definitive way of eliminating the pestis bacteria from contaminated buildings and soil.8 Bodies of plague victims were required to be cremated, a concept that sparked fear and protest from the Chinese, who often sent the bones of the dead back to China to be buried with ancestors, lest the spirit be condemned to wander.9 Those who lived and worked in plague-infested buildings had their homes and businesses burned to the ground and were relocated to quarantine camps. On arrival, newcomers were stripped and sprayed with disinfectant under the watchful eyes of the all-male, all-white officers. This procedure, among others in the invasive course of seizure and quarantine, evoked bitter protests: “The shame, the black, black shame . . . brought upon our women, our wives, the mothers of our children! . . . forced to stand naked, stark naked in the streets for the white devils to see, for the whole world to see!”10

|

| Figure 2. Chinatown fish market circa 1900. D. H. Wulzen Glass Plate Negative Collection (SFP 40), San Francisco History Center, San Francisco Public Library |

While many in the white business community advocated the wholesale burning of Chinatown, the board physicians held fast to their policy of only burning buildings where plague had been confirmed, which included an increasing number of white-owned businesses and residences outside of Chinatown. The morning of January 20, 1900 was bright and calm. It seemed an ideal day to carry out the planned burning of two buildings near Kaumakapili Church, as a light breeze was blowing away from the historic landmark. The work was going according to plan until the wind suddenly changed direction and strong gusts carried flames and debris across the district. Firefighters worked in vain to contain the blaze and soon had to evacuate the area themselves. A frightened throng of thousands ran from the flames, carrying children and the few possessions they could grab before fleeing, only to be met by a crowd of white men armed with axes, baseball bats, and pickets, determined to keep the Chinatown infestation from crossing into their part of the city.11

The Honolulu Chinatown fire burned for seventeen days, destroying thirty-eight acres and 4,000 homes.12 The news of the conflagration was still fresh for the Chinese community of San Francisco when plague was discovered in that city just weeks later. Wong Chut King, a laborer at a rat-infested lumberyard where residents came to look for old timber to repair dilapidated dwellings in San Francisco’s Chinatown, was found dead of suspected plague in February 1900. Many poor laborers like Wong lived crowded together in basement dwellings where the rent was cheapest and the rats found their way up through the sewers, again having arrived on ships docked in the nearby harbor.13,14 The residents, mostly men who had been enticed by industry to work in mining and railroad construction, were now effectively forced to live within the boundaries of the Chinatown district, threatened with violence and racism from labor leaders who believed that Chinese “coolies” were threatening American jobs, and a white population that believed Asians brought disease, crime, and an inability to assimilate into Western culture.15 These perceived threats had been codified into US law with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which prevented Chinese workers from entering the country with the argument that “Mongolians are alien to our civilization, alien in blood, alien in faith . . . they are a degraded people.”16

As more cases of plague were discovered, city health officials responded to the threat by quarantining San Francisco’s entire Chinatown district. Forced home inspections by health officials accompanied by armed police resulted in complaints of invasion of privacy, theft, and rape. Sick and dying people were often hidden from inspectors out of fear of cremation, loss of property, deportation, and expulsion. Many prominent leaders in business and government, having wished for years to redevelop the prime real estate on which Chinatown was located, advocated in newspaper editorials that the only way to “get rid of that menace [plague] is to eradicate Chinatown from the city . . . clear the foul spot from San Francisco and give the debris to the flames.”17

The months that followed included disputes between government officials, many of whom wanted to simply dismiss the idea that plague existed in San Francisco; disagreements within the medical community, especially between proponents and opponents of the still emerging field of bacteriology; a failed trial of inoculation; inflammatory headlines and editorials; ongoing quarantines and home inspections; and the continuous threat to use fire as a means of eradication. At the end of the outbreak, which lasted four years, there were 119 confirmed cases of plague in San Francisco.18 The number of unreported cases in Chinatown and uninvestigated cases in other parts of the city were undoubtedly much higher. Plague briefly returned to San Francisco in the aftermath of the 1906 earthquake. No reported deaths occurred within Chinatown during that outbreak, and the disease was much more quickly contained because of citywide efforts to eradicate rats.19

Louis Pasteur, the renowned giant of the field of microbiology, famously stated, “Where observation is concerned, chance favors only the prepared mind.”20 The plague pandemic that was still ongoing at the turn of the twentieth century occurred at a time of rapid scientific advancements, which are frequently met with initial skepticism and doubt. The outbreaks in the United States and its territories occurred against a backdrop of xenophobia and racism that had even been codified into national law. It has been argued that the health officials in Honolulu and San Francisco were acting according to the accepted theories and practices of the time, many of which would be overturned a few years later with reports such as that from U.S. Surgeon General W.H. Kellogg, who had been San Francisco’s bacteriologist during the years of plague: “The message I would carry to the ears of government, national, state and municipal authorities, were it possible to do so, would be: Wage a relentless warfare against the rat in all the seaports of this country regardless of whether or not plague has yet appeared.”21 In other words, the focus should have been on the rats all along, not on profiled groups of humans that were suspected of carrying disease.

The contamination of public health with racism has not yet abated in the twenty-first century. As COVID-19 became a pandemic in late 2019 and early 2020, Asians across the world reported an increase in racial slurs, xenophobia, and violence. In the United States, a group of advocacy organizations created a reporting tool for hate incidents against Asians, and collected more than 1,200 reports of verbal and physical violence in the first week alone.22 Outside a Chinatown restaurant in Sydney, Australia, a group of bystanders watched a man die of a cardiac arrest, with no one intervening for fear of contracting coronavirus.23 A group of Asian-American teens created an educational film documenting their experiences with classmates describing Chinese people as “dirty” and “disgusting.”24 Video footage of verbal slurs and physical assaults on people of Asian ancestry has been shared on digital and social media platforms. Three family members in Texas, including two young children, were stabbed by a man accusing them of carrying coronavirus. An Asian-American architect in New York City summarized her feelings: “You just bury your head and you move forward because no matter how hard you work, how successful you are, what friends you make, you just don’t belong. You will always be looked at as foreign.”25

The author Maya Angelou once said, “Do the best you can until you know better. Then when you know better, do better.”26 Today, in the twenty-first century, 120 years after the plague epidemics of Honolulu and San Francisco, and in the midst of a pandemic that has affected the entire world, surely we have learned that if a pathogen such as COVID-19 threatens one of us, it affects all of us. Our vulnerability and our strength is codified in the condition of being human, connected in a global community, not in the superficial differences that penetrate no further than the level of our skin.

References

- Mohr, James C. Plague and Fire: battling Black Death and the 1900 Burning of Honolulu’s Chinatown. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005, p. 8 – 29.

- Crawford, Edward A. Jr. “Paul-Louis Simond and His Work on Plague.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 39, no. 3 (1996): 446-458.

- Mohr, Ibid, p. 10 – 12.

- Crawford, Ibid.

- Kil, Sang Hea. “Fearing Yellow, Imagining White: Media Analysis of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.” Social Identities 18, no. 6 (2012): 663-77

- Mohr, Ibid, p. 201.

- Ibid, p. 14.

- Ibid, p. 88.

- Ibid, p. 68.

- Ibid, p. 150.

- Ibid, p. 133.

- Hawaii Digital Newspaper Project. “The Chinatown Fires.” https://sites.google.com/a/hawaii.edu/ndnp-hawaii/Home/subject-and-topic-guides/the-chinatown-fires

- Risse, Guenter B. Plague, Fear, and Politics in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012, p. 19 – 25.

- Tansey, Tilli. “Plague in San Francisco: Rats, Racism and Reform.” Nature 568, no. 7753 (2019): 454-455.

- Kil, Ibid.

- Risse, Ibid, p. 6.

- Ibid, p. 147.

- Ibid, p. 269.

- Dolan, Bryan. “Plague in San Francisco 1900.” Public Health Reports, 2006 Supplement 1, Vol 121.

- Pasteur, Louis. Lecture, University of Lille (7 December 1854). https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Louis_Pasteur

- Kellogg, W.H. “Current Status of Plague with Historical Review.” American Public Health Association, September 15, 1920.

- “Asian Americans describe ‘gut punch’ of racist attacks during coronavirus pandemic.” PBS News Hour, April 7, 2020. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/asian-americans-describe-gut-punch-of-racist-attacks-during-coronavirus-pandemic.

- “The Pandemic of Xenophobia and Scapegoating.” TIME, March 7, 2020. https://time.com/5776279/pandemic-xenophobia-scapegoating/

- “Coronavirus Racism Infected My High School.” New York Times, March 20, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/20/learning/film-club-coronavirus-racism-infected-my-high-school.html

- PBS News Hour, Ibid.

- Angelou, Maya. Attributed. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/7273813-do-the-best-you-can-until-you-know-better-then

ANNE JACOBSON, MD, MPH, is a family physician, writer, consultant, and editor. Her published works may be found in Hektoen International, The Examined Life Journal, The Journal of the American Medical Association, in the anthology At The End of Life: True Stories About How We Die, and others. A collection of her writing may be found at www.thewritetowander.com. She is the Associate Editor of Hektoen International Journal of Medical Humanities.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 3 – Summer 2020

Spring 2020 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply