Mariel Tishma

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

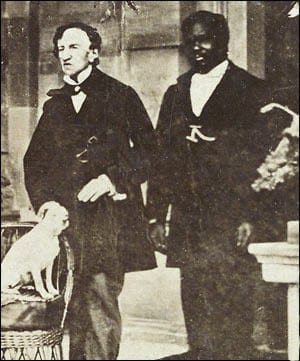

| Dr. James Barry with John, a servant, and his dog, Psyche. Unknown Artist. c1850. |

“Do not consider whether what I say is a young man speaking, but whether my discussion with you is that of a man of understanding.”1 – Dedication of the thesis of James Barry

In November of 1809, a ship set sail from London towards Edinburgh. Aboard was a young man with roughly cut red hair traveling with his aunt. On arrival, he would enroll in medical school at the University of Edinburgh, and graduate MD three years later. In his later successful career as a military surgeon he would advocate for public health, and perform one of the first Cesarean sections in which both mother and baby survived. His name was James Miranda Steuart Barry.

But another story dominates the legacy of this skilled surgeon; Dr. James Barry was born Margaret Ann Bulkley. (This article will use male pronouns and the name Dr. James Barry throughout.)

Dr. Barry’s decision to live and practice medicine as a man for over fifty years has come to define him, for better and for worse. One may ask, did James Barry live as a man to advance his career? Was he transgender? Or did he act outside of these boundaries entirely?

Barry was born in 1789 in Cork, Ireland. His father, Jeremiah Bulkley ran a grocery at Merchant’s Quay.2 Money was tight, and the Bulkleys placed their hope in Barry’s older brother, John Bulkley, who apprenticed to a lawyer in Dublin, and later married a woman of a higher class. Both endeavors drained the family resources. Barry’s father Jeremiah was eventually sent to debtor’s prison,3 and John Bulkley vanished, leaving Barry and his mother, Mary Ann Bulkley, alone.4, 5

There was little they could do to support themselves. Neither were educated enough for the professions available to them, and relatives with funds were few. The best option was Mary Ann’s brother, James Barry, a painter and professor at the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Mary Ann reached out to him several times, but he declined to help.6

The painter died of a respiratory illness in 1806.7 He left no will, and so his estate was divided between his next of kin: Mary Ann and one other Bulkley brother. The profit from the sale of the estate did not amount to as much as hoped, but it was enough to keep Mary Ann and her child out of destitution. On the trip to settle affairs, the younger Barry was introduced to a few of the painter’s supporters, a band of intellectuals and statesmen who would become instrumental to his own career.8

Mrs. Bulkley and James Barry, still living as a woman, moved to London. Mary Ann shifted her hopes for stability to her remaining child. He was to be instructed by friends of her brother, gaining the skills of a tutor or governess. This would provide money, and a reputation good enough to secure a marriage.

Barry began lessons under Dr. Edward Fryer, which may have been his first introduction to medicine. Barry also tutored the son of General Francisco Miranda, a revolutionary working to liberate his native Venezuela and a friend of the elder James Barry.9

Here, Barry showed his aptitude for learning. The general had an extensive library in London, and Barry took full advantage of the literature.10 His ambition suggested a grander future, though this was impossible while living as a woman. Eventually a plan was formed; Barry would live as a man and attend medical school, paying tuition with the profits from the estate. After graduation, Barry would join General Miranda in Venezuela and practice medicine there as a woman again. It was likely Miranda who proposed the plan, knowing that the revolution would require skilled doctors and surgeons. Barry agreed, and with the help of his mother and his uncle’s friends, the plan was put in motion.

The fateful November arrived, and Barry, now dressed as a man, traveled from London with his mother, now described as his aunt, to Edinburgh. The two cut all contact with their old life. The only connection left was the lawyer, Daniel Reardon, who managed the money from James Barry’s estate.11 Reardon was one of the few who knew about Barry’s new life. Also included were General Miranda and Dr. Fryer.12

It is not known if Barry had a desire to study medicine in his youth. It is also hard to say for certain if Barry was questioning his gender when he began his education. We do know that in one letter to his brother John, written before living as a man, Barry wrote, “Was I not a girl I would be a Soldier!”13 Later in life, Barry would describe himself exclusively as a gentleman, which is the clearest assessment he provided of his own gender.

Barry enrolled in classes in December of 1809. He thrived during his three years at Edinburgh. His required courses included anatomy, surgery, chemistry, materia medica, and botany, as well as medical theory and clinical lectures. He also added a practical anatomy course with Andrew Fyfe,14 classes in military surgery, dissection lectures, and many courses in midwifery.15

In the summer of 1812 James Barry was ready to graduate. His thesis, written entirely in Latin, was on femoral hernia. There would be a written and oral exam, followed by thesis defense, all also in Latin. However, the university attempted to bar Barry from the examinations, believing he was too young to graduate. As he was unable to grow a beard Barry was often perceived as a young boy, rather than a man.

Early in his school years, Barry was introduced to David Steuart Erskine, Earl of Buchan, another supporter of his uncle.16 As he struggled to graduate, Lord Buchan addressed the university on his behalf, stating that there was no rule for a minimum age of examination. Barry earned his MD in July of 1812.

The victory of graduation was bittersweet. Around this same time, General Miranda was betrayed and imprisoned until he died in 1816.17 Barry was now trapped. Returning to living as a woman would be a waste of three years’ effort, but in order to practice medicine he would have to continue living as a man. James Barry chose medicine, whatever his motivation.

Dr. James Barry moved to London as a student at Guy’s and St. Thomas’ Hospital. There he polished his skills and followed Sir Astley Cooper on rounds.18 After six months of study, Barry applied to the British Military in June of 1813.19 He passed the skills examinations for an army surgeon, and his assessment of his health as a gentleman was suitable in place of a medical examination.20, 21

He spent time in Plymouth, England, before being promoted to assistant surgeon and sent to South Africa in 1816. Here Dr. Barry would make a name for himself. He was appointed personal physician to Lord Charles Somerset, the governor of the Cape, in December of 1817.22 Somerset would promote Barry to Colonial Medical Inspector in 1822, but their association came with controversy. Rumors spread about a romantic and intimate relationship between the two23—illegal at the time. But this scandal did not slow Barry’s work.

Once in charge of the South African colony’s entire health system as colonial inspector, Barry immediately began reforming. He required medical professionals to be regulated, licensed, and certified; improved care for those with leprosy; investigated water systems to reduce corrosion; and improved conditions for prisoners and asylum patients as well as promoting sanitation, vaccinations, and quarantining ships. But this did not make him popular. Many pushed back against his efforts, and Dr. Barry made many enemies.24

However, no one denied that Barry was an excellent surgeon and physician. Despite his acerbic personality with rivals and peers, he was gentle and understanding with patients,25 and his surgical skill led to success in one of the most high-risk operations of the time.

In 1826, one of Dr. Barry’s private patients in South Africa, Wilhelmina Munnik, was struggling with a hard delivery.26 Dr. Barry decided to operate. C-section deliveries were mostly performed “to deliver live babies from dead mothers,” or, more tragically, “to deliver dead babies from dead mothers,”27 so attempting the surgery was dangerous. But Dr. Barry prevailed, and both mother and son survived.

Barry was then promoted to Army Medical Inspector—one of the most senior positions in the British Army28—and moved often. His postings included Jamaica, Mauritius, St. Helena Island, Trinidad, Malta, and Corfu.29, 30 At each post he helped colonies manage diseases like cholera, and faced push-back due to his reforming spirit and strong personality.

Barry briefly aided soldiers of the Crimean War and worked with Florence Nightingale. The two did not get along. In a later letter, Nightingale described Barry as a “brute” and one of the “most hardened creatures” she had met in the army.31

Some described Barry as a “dandy.” He was said to be particular about his dress, irritable, and sensitive about his height. As a result of his disposition, he participated in at least one duel.32 Barry was also intensely private. He formed few close relationships, never married, and lived only with a servant and a dog named Psyche.33

One may wonder how much of his personality was an effect of his secret or an effort to be more masculine. Barry may have been short tempered and sensitive for fear of being discovered, or out of disappointment at his feminine traits. Perhaps his personality was an expression of freedom. Men at the time could be as confrontational as they liked and still be respected. And Barry’s bold, assertive spirit enabled many of the positive changes he made.

Dr. Barry was transferred to his final post in Canada in 1857. Here he advocated for better housing and nutrition, actively improving the lives of the lower ranks and their families.34 But some combination of Canadian weather and a difficult life began to take a toll. Barry grew ill with bronchitis and was sent back to London in 1859, then discharged due to his illness. He fought fiercely to return to service, but was denied.

In London he declined and died from dysentery in July of 1865.

If Barry’s wishes after his death had been respected his past may never have been revealed. Barry did not want his body examined and asked to be buried in the clothes he had died in, as soon as possible.35 He wanted his past a secret—and to be seen as a man after death, perhaps as part of a desire to be remembered as the gender he identified with, not the one he was assigned.

Even so, Barry’s request for a quick burial was not fulfilled; a charwoman named Sophia Bishop washed and examined his body. She reported that Dr. Barry was a “perfect female.”36 Her report was not authenticated by anyone, though handwriting analysis and letters from Daniel Reardon later connected James Barry to Margaret Ann Bulkley.37 Bishop attempted to use this information to extort Staff Surgeon Major D. R. McKinnon, a friend and doctor of Barry’s, for payment. When he refused, writing “it was none of my business whether Dr Barry was a male or a female,”38 she sold her story. The military then sealed Barry’s records for nearly 100 years,39 though speculation continued.

Theories propose that James Barry was intersex or a hermaphrodite, that he had attended medical school to follow a male lover (a story popular in pulp novels at the time40), that he was transgender, or that Barry identified as a woman and lived as a man only to advance a career. This last theory is one of the most popular, its supporters stating that Barry was the first woman to serve in the British military, despite Barry’s describing himself as a gentleman throughout his adult life.

Ignoring speculation, we can say for certain that James Barry was an advocate of public health and a skilled and dedicated surgeon. The center of his life was his work, and through it he improved and saved many lives.

We cannot define the interior life of James Barry. If Barry did identify as another gender—if he was a transgender man as it is understood today—he would not have had the language to say so. But we have his actions, and these reflect someone who lived as a man for nearly half a century and wished to be known as a man after his death. In this way, James Barry is a reminder that LGBTQ+ stories are often shrouded, confused, or misrepresented but have been, and will always be, an essential part of history.

End Notes

- Rachel Holmes, Scanty Particulars: The Scandalous Life and Astonishing Secret of James Barry, Queen Victoria’s Most Eminent Military Doctor, 1st ed. (New York: Random House, 2002), 311.

- Hercules Michael du Preez, “Dr James Barry: The early years revealed,” South African Medical Journal vol.98 n.1 (January 2008): 52-54, http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0256-95742008000100025.

- Robert Hume, “THE ANATOMY OF A LIE – The Irish woman who lived as a man to practice medicine,” The Irish Examiner, August 01, 2014, https://www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/features/the-anatomy-of-a-lie-277445.html.

- HM du Preez, “Dr James Barry (1789–1865): the Edinburgh years,” The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh vol. 42, no. 3 (2012): 258-259, http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2012.315.

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time, (London: Oneworld Publications, 2016), 3-12. eBook.

- HM du Preez, “Dr James Barry (1789–1865): the Edinburgh years,” 259.

- Robert Hume, “THE ANATOMY OF A LIE,” The Irish Examiner.

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time, 28.

- Ibid, 34-35.

- Hercules Michael du Preez, “Dr James Barry: The early years revealed,” 54.

- HM du Preez, “Dr James Barry (1789–1865): the Edinburgh years,” , 259-260.

- Hercules Michael du Preez, “Dr James Barry: The early years revealed,” 54.

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time, 50.

- Ibid, 70-71.

- Howard Phillips, “Home Taught for Abroad: The Training of the Cape Doctor, 1807-1910” in The Cape Doctor in the Nineteenth Century: A Social History, Edited by Harriet Deacon, Howard Phillips, E. Van Heyningen, (New York, NY: Editions Rodopi B.V., Amsterdam, 2004), 115.

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time, 66.

- Hercules Michael du Preez, “Dr James Barry: The early years revealed,” 54.

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time, 87.

- Lauren Young, “Why This Groundbreaking British Doctor Was Almost Erased From the History Books,” Atlas Obscura, December 22, 2016, https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/dr-james-barry-gender.

- AK Kubba, M Young, “The Life, Work and Gender of Dr James Barry Md (1795-1865),” The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh vol. 31, no. 4 (2001): 352, https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/college/journal/life-work-and-gender-dr-james-barry-md-1795-1865#text

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time, 101.

- AK Kubba, M Young, “The Life, Work and Gender of Dr James Barry Md (1795-1865),” 352.

- Rachel Holmes, Scanty Particulars, xi.

- AK Kubba, M Young, “The Life, Work and Gender of Dr James Barry Md (1795-1865),” 352.

- EE Ottoman, “Dr. James Barry and the specter of trans and queer history,” This Journey Without A Map (blog), November 24, 2015, https://acosmistmachine.com/2015/11/24/dr-james-barry-and-the-specter-of-trans-and-queer-history/.

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, “Dr James Barry: The woman who fooled the RCS and deceived the world,” The Bulletin of The Royal College of Surgeons of England vol. 98 no. 9 (October 2016): 398, https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsbull.2016.396.

- John F O’Sullivan, “Caesarean birth.,” The Ulster medical journal vol. 59, no1 (1990): 1, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2448256/?page=1.

- Robert Hume, “THE ANATOMY OF A LIE,” The Irish Examiner.

- Charles G. Roland, “BARRY, JAMES,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barry_james_9E.html.

- Kathleen M. Smith, “Dr. James Barry: military man – or woman?” Canadian Medical Association journal vol. 126, no. 7 (1982): 856, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1863077/.

- Robert Hume, “THE ANATOMY OF A LIE,” The Irish Examiner.

- EE Ottoman, “Dr. James Barry and the specter of trans and queer history.”

- Lauren Young, “Why This Groundbreaking British Doctor Was Almost Erased From the History Books.”

- EE Ottoman, “Dr. James Barry and the specter of trans and queer history.”

- Hamish Copley, “Dr. James Miranda Barry,” The Drummer’s Revenge (blog), December 2, 2007, https://thedrummersrevenge.wordpress.com/2007/12/02/dr-james-miranda-barry/.

- Hercules Michael du Preez, “Dr James Barry: The early years revealed,” 52.

- Ibid. 53.

- AK Kubba, M Young, “The Life, Work and Gender of Dr James Barry Md (1795-1865),” 355.

- Michael du Preez, Jeremy Dronfield, “Dr James Barry: The woman who fooled the RCS and deceived the world,” 397.

- Alex Myers, “Wearing the Pants,” Slate, The Slate Group, July 02, 2018, https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/07/women-masquerading-as-men-stories-damage-transgender-understanding.html.

Bibliography

- Copley, Hamish. “Dr. James Miranda Barry.” The Drummer’s Revenge (blog). December 2, 2007. https://thedrummersrevenge.wordpress.com/2007/12/02/dr-james-miranda-barry/.

- du Preez, HM. “Dr James Barry (1789–1865): the Edinburgh years.” The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh vol. 42, no. 3 (2012): 258-265. http://dx.doi.org/10.4997/JRCPE.2012.315.

- _____. “Dr James Barry: The early years revealed.” South African Medical Journal vol.98 n.1 (January 2008): 52-58d. http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0256-95742008000100025.

- Du Preez, Michael, Jeremy Dronfield. Dr James Barry: A Woman Ahead of Her Time. London: Oneworld Publications, 2016. EBook.

- _____. “Dr James Barry: The woman who fooled the RCS and deceived the world.” The Bulletin of The Royal College of Surgeons of England vol. 98 no. 9 (October 2016): 396-398. https://doi.org/10.1308/rcsbull.2016.396.

- Holmes, Rachel. Scanty Particulars: The Scandalous Life and Astonishing Secret of James Barry, Queen Victoria’s Most Eminent Military Doctor. 1st ed. New York: Random House, 2002.

- Hume, Robert. “THE ANATOMY OF A LIE – The Irish woman who lived as a man to practice medicine.” The Irish Examiner. August 01, 2014. https://www.irishexaminer.com/lifestyle/features/the-anatomy-of-a-lie-277445.html.

- Kubba, AK, M Young. “The Life, Work and Gender of Dr James Barry Md (1795-1865).” The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh vol. 31, no. 4 (2001): 352-356. https://www.rcpe.ac.uk/college/journal/life-work-and-gender-dr-james-barry-md-1795-1865#text.

- Myers, Alex. “Wearing the Pants.” Slate, The Slate Group. July 02, 2018. https://slate.com/human-interest/2018/07/women-masquerading-as-men-stories-damage-transgender-understanding.html.

- O’Sullivan, John F. “Caesarean birth.” The Ulster medical journal vol. 59, no1 (1990): 1-10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2448256/?page=1.

- Ottoman, EE. “Dr. James Barry and the specter of trans and queer history.” This Journey Without A Map (blog). November 24, 2015. https://acosmistmachine.com/2015/11/24/dr-james-barry-and-the-specter-of-trans-and-queer-history/.

- Phillips, Howard. “Home Taught for Abroad: The Training of the Cape Doctor, 1807-1910” in The Cape Doctor in the Nineteenth Century: A Social History. Edited by Harriet Deacon, Howard Phillips, E. Van Heyningen. New York, NY: Editions Rodopi B.V., Amsterdam, 2004.

- Riedel, Samantha. “James Barry Is Not Your Rorschach Test.” them., Condé Nast. February 27, 2019. https://www.them.us/story/james-barry-ej-levy.

- Roland, Charles G. “BARRY, JAMES.” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 9, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/barry_james_9E.html.

- Smith, Kathleen M. “Dr. James Barry: military man – or woman?” Canadian Medical Association journal vol. 126, no. 7 (1982): 854-857. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1863077/

- Young, Lauren. “Why This Groundbreaking British Doctor Was Almost Erased From the History Books.” Atlas Obscura. December 22, 2016. https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/dr-james-barry-gender.

MARIEL TISHMA is the Executive Editorial Assistant at Hektoen International. She has been published in Hektoen International, Bloodbond, Argot Magazine, Syntax and Salt, The Artifice, and Fickle Muses. She graduated from Columbia College Chicago with a BA in creative writing and a minor in biology. Learn more at marieltishma.com.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 3 – Summer 2020 and Volume 14, Issue 1 – Winter 2022

Spring 2020 | Sections | Physicians of Note

Leave a Reply