|

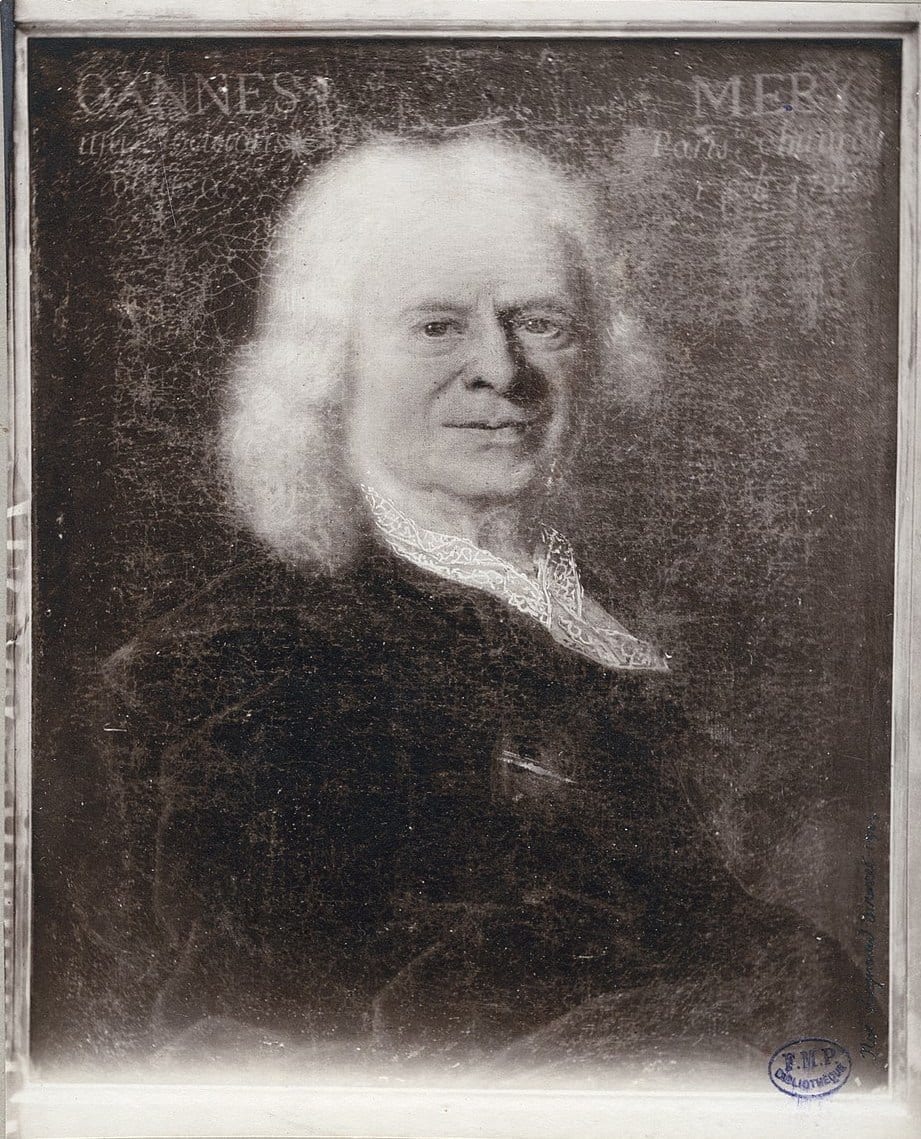

| Jean Mery. Unknown artist. Collège de chirurgie, Bibliothèque interuniversitaire de santé: CIPB1509. |

Jean Mery lived largely in the days of the Sun-King Louis XIV, when France was still rich and powerful and had not yet spent itself into bankruptcy. Born in central France in 1645, he followed in his father’s footsteps at eighteen and went to Paris to become a surgeon.

In Paris his life was largely intertwined with the famous Hotel Dieu hospital, then the best place to obtain a surgical education. But seemingly dissatisfied with what he was taught during the day, he spent his nights in his room dissecting cadavers he had obtained illegally, dissection not being allowed in France at that time.

Graduating with a thesis on the anatomy of the ear, he was appointed surgeon at the Hotel Dieu in 1681 and later became chief surgeon. He set up a private practice in Paris and as his career progressed he received appointments as chief surgeon to the queen and senior surgeon at the Invalides hospital for veterans. He was also sent to Lisbon to consult on the illness of the Queen of Portugal, but she died before he could get there. Despite being offered lucrative positions in Portugal and Spain, he decided to return to France and was elected to the Academy of Sciences. In 1692 he was sent by the court on a medical mission to England.

In his private life he has been described as being taciturn and argumentative, often seeing his family only at meals. As a dedicated teacher, he stressed the importance of careful observation. He studied the respiratory pathways, parts of the eye, and the fetal circulation, but obstinately held, on to his death, several controversial physiology ideas that were soon proven to be erroneous. But he was a competent anatomist and described several structures, such as the eustachian tube and the urethral glands, for which he received no recognition in that they were later described by other investigators and named after them. In Paris he was known to have an extensive anatomy cabinet of human and animal specimens that he himself had carefully dissected, notably a display of nerves from origin to insertion that he had spent many years to dissect. He had been in good health all his life, but at the age of seventy-five lost the use of his legs and died two years later in 1722.

GEORGE DUNEA, MD, Editor-in-Chief

Leave a Reply