Cristóbal Berry-Cabán

Fort Bragg, North Carolina, United States

“At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk.”1 Thus begins John Hersey’s Hiroshima about the effects of the first atomic bomb that was dropped seventy-five years ago.

Earlier that day the Enola Gay, a B-29 bomber, had taken off from Tinian Island heading towards Japan 1,500 miles away. Hiroshima, the primary target, was an important military and communications center with a population of about 300,000. The bomber flew at low altitude before climbing to 31,000 feet as it neared the target, releasing a 9,700-pound uranium bomb nicknamed Little Boy. Forty-three seconds later a huge explosion lit the morning sky as Little Boy detonated 1,900 feet above the city.

Within hours of the Hiroshima bombing, radio stations read a statement from President Harry S. Truman informing the public that “An American airplane [has] dropped one bomb on Hiroshima . . . It is an atomic bomb. It is a harnessing of the basic power of the universe.”2

Three days later the Bockscar released Fat Man. This bomb exploded high over the industrial valley of Nagasaki, destroying the Mitsubishi Arms Factory that had manufactured the torpedos dropped on Pearl Harbor. An estimated 39,000 people were killed outright.3

Figure 2. Mushroom cloud over Hiroshima, August 6, 1945. National Archives.

Japan’s surrender signaled the end of World War II. As America celebrated the victory, the atomic bomb hung like some unnerving haze from another world. Americans tried to make jokes: “when God made Atom, he sure created a handful for Eve.” Few Americans were sententious as most believed that atomic energy would usher in a golden age of peace.

A few voiced dissent. John Foster Dulles intimated that atomic bombs and “Christian statesmanship” were incompatible: “If we, as a professedly Christian nation, feel morally free to use atomic energy in that way, men elsewhere will accept that verdict. Atomic weapons will be looked upon as a normal part of the arsenal of war and the stage will be set for the sudden and final destruction of mankind.”4 Yet scores of leaders answered hotly that a truly Christian nation ended wars as quickly as possible.

It was a full year before most Americans became aware of the deadly health effects of the atomic bombs. On August 31, 1946, The New Yorker devoted an entire issue of its magazine to the accounts of six survivors interviewed by Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Hersey.5 Hersey’s interviews, later published as Hiroshima, became an instant classic.1

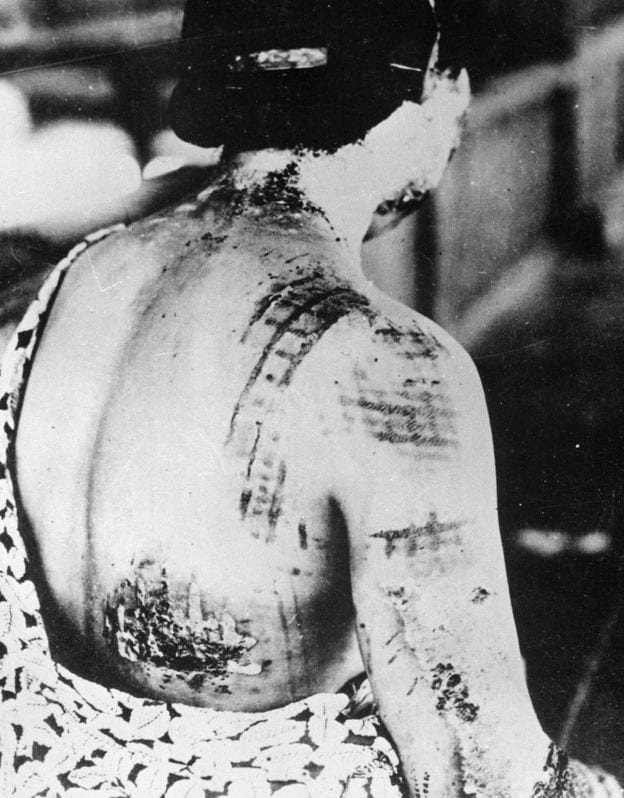

Hiroshima vividly describes the bomb’s horrifying aftermath: people with melted eyeballs; people vaporized, leaving only their shadows etched onto walls; descriptions of how people’s skin would fall off when someone tried to pull them out of the water; the extensive burns where there was no skin, just muscle and bone.

Hiroshima testifies to the unnatural, unbelievable power of the atomic bomb. The bomb turned day into night, conjured up rain and wind, and destroyed beings from the inside as well as from the outside. Hersey introduces compelling statistics, citing the number of people killed or injured and the reasons why many of those who died could have been saved. Nearly half of the 150 doctors in the city were killed instantly and few of those who survived had access to hospitals or medical equipment.

By combining these statistics with six first-hand accounts, Hersey personalizes the tragedy, and adds meaning to the numbers of dead and wounded. Hersey rarely takes the focus away from these six main figures, and through their experiences we are able to get a vivid picture of the destruction. The characters see countless homes collapsed and hear cries of “Tasukete kure!” (“Help, if you please!”) coming from under the rubble. Hersey describes everything from the bomb’s effects on the weather to the types of burns many people suffered. In fact, Hersey takes great pains to show his readers how the atomic bomb was uniquely devastating.

Before Hiroshima appeared in press most Americans at this time were unaware of the power of the atomic bomb. Speed and secrecy had been the watchwords of the Manhattan Project, the program that developed and built the bombs. When the Trinity test explosion occurred in the New Mexico desert it was announced by the local media (cooperating with the U.S. Office of Censorship) as “a harmless accident in a remote ammunition dump.”6 After the bombings, access to Hiroshima and Nagasaki was severely restricted by American occupation forces. In 1946, it was still common for American military leaders to depict the event as just another bombing mission.6

Hersey was the first to pierce through the official pronouncements. After Hiroshima appeared in the New Yorker, Albert Einstein ordered 1,000 copies. Hersey’s essay aroused American empathy for the victims.7

This devastating attack on Hiroshima and Nagasaki not only garnered Japan’s surrender, but also planted a seed of fear in the world. Some will debate it was the first time that the United States was seen as a force to be reckoned with, while others perceive it as one of the most horrific and inhumane acts committed. These points of view are crucial to the perception of nuclear weapons in America decades later. During the 60s, at the height of the Cold War and Cuban Missile Crisis, the United States found itself in a frightening situation regarding nuclear weapons. While the conflict never culminated, the fear of being victims to a nuclear fallout permeated the minds of many Americans. The goal of eliminating such weapons is entirely laudable. But the world has changed in so many ways in seventy-five years since the bombing.

Physicist Harold Agnew, who served as a scientific observer and watched the destruction of Hiroshima from an observer plane, thought that every world leader should be forced to feel the heat on his or her face from a nuclear blast.8 The number of people who have actually experienced such a thing dwindles each year. In the absence of first-hand experience, every leader and every literate person should read Hiroshima, which eloquently conveys what is at stake.

Disclaimer

The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the US Army Medical Department, Department of Army, Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense or the US Government.

References

- Hersey J. Hiroshima. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1946.

- Truman HS. Statement on the Atomic Bomb, August 8. 1945. Public Papers of the Presidents: Harry S. Truman. Vol 1 1945.

- Southard S. Nagasaki: Life After Nuclear War. Viking; 2015.

- Rosendorf N. John Foster Dulles’ Nuclear Schizophrenia. In: Gaddis JL, Gordon PH, May ER, Rosenberg J, eds. Cold War Statesmen Confront the Bomb: Nuclear Diplomacy since 1945. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999:62-86.

- Hersey J. Hiroshima. The New Yorker. 1946.

- Rhodes R. The Making of the Atomic Bomb. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1986.

- Shorto R. John Hersey, the Writer Who Let “Hiroshima” Speak for Itself. The New Yorker. 2016.

- Schlosser E. Eric Schlosser: Why Hiroshima now matters more than ever. The Telegraph. August 2, 2015.

CRISTÓBAL S. BERRY-CABÁN, PhD, a graduate of the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, has over 30 years’ experience conducting research in health. He is an epidemiologist at Womack Army Medical Center and associate professor at Campbell University. He is the author of nearly 100 research articles including several articles on the history of medicine.

Leave a Reply