Carol Sherman

Chicago, Illinois, United States

|

|

Figure 1. The sign from the Mustard Museum. Photo taken by Douglas R. Siefken, August 15, 2019. Provided for this article. |

The National Mustard Museum in Middleton, Wisconsin1 describes itself as having over 5,600 mustards. They originate from all fifty states of the United States and from more than seventy countries. This museum, casting itself as midcentury, exhibits old curios and vintage signage. The museum also provides a place to sit on metal seats to learn the history of mustard as well as being schooled through videos on recipes from international chefs.

Mustard has a long history, and has more uses than merely putting yellow mustard on a frankfurter (although that is a great application!). One learns that mustard seeds leave a trail, produce commerce, and may even offer health benefits.

The mustard seed and its historical origins

According to archaeologists and botanists, mustard seeds have been found in Stone Age settlements.2 During the Sumer period of Mesopotamia, the Sumerians would grind the mustard seed into a paste and mix it with verjus, the juice of unripe grapes, which is highly acidic. An urban development occurred in the region on account of surpluses from farming the seeds.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the ancient Egyptians also flavored their food with mustard, as shown by mustard seeds being found in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

To create mustard condiments, “the Romans ground mustard seeds and mixed them with wine into a paste not much different from the prepared mustards we know today.” The use of the seed spread to Gaul, took root in Europe, and was there even before the commerce of spices traveled from Asia. In Europe, the French monasteries cultivated and sold mustard as early as the ninth century, and the condiment was for sale in Paris by the thirteenth century. Mustard appeared in Spain with the arrival of the Roman legions, then in India with Vasco de Gama.3

It has been reported that around AD 1000, Pope John XII loved mustard so much that he created a Vatican position for a mustard maker, grand moutardier du pape (mustard-maker to the pope), who came from the Dijon region. He assigned this position to his “idle nephew who lived near Dijon,” to fill the role. (“Idle” is a code word for lazy, by the way.) Considering that there has to be the right climate and soil for the mustard seed, we have the recipe for branding mustard for centuries.2

By the 1770s, mustard took a modern turn when Maurice Grey and Antoine Poupon introduced it to the world as Grey Poupon Dijon mustard. Their original store can still be seen in downtown Dijon in eastern France. In 1866, Jeremiah Colman, founder of Colman’s Mustard of England, was appointed mustard-maker to Queen Victoria.4 Colman perfected the technique of grinding mustard seeds into a fine powder without creating the heat that brings out the oil. Fast forward to the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, where an international community enjoyed a hot dog with yellow mustard (a first) introduced by the R.T. French Company. (By the way, the hot dog was first created in 1805. It took around 100 years for the dog to meet its companion.)

|

|

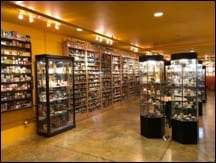

Figure 2. Mustard Museum’s Historical Mustards. Photo taken by Douglas R. Siefken, August 15, 2019. Provided for this article. |

The mustard seed from a species of plants

Mustard is a plant that some have identified as a shrub because its stalks look like a tree. There are at least forty species of mustard plants. Among the most popular for making mustard condiments are black mustard—Brassica nigra originating from the Middle East and Asia Minor—brown Indian mustard from the Himalayas—Brassica juncea—and white/yellow mustard—Brassica hirta from the Mediterranean basin.2,5

Mustard for medicinal purposes

Throughout history, the interest in mustard as a condiment has been complemented by the pursuit to apply it for medicinal uses. As early as the sixth century BC, Pythagoras recommended mustard as remedy for scorpion stings. A hundred years later, Hippocrates used mustard in medicines and poultices. Mustard plasters were applied to treat toothaches and also several other ailments. The Greeks preceded the Romans by using mustard as a cure for anything from hysteria to snakebite to bubonic plague.

It is by no means clear how mustard seeds and the condiment may improve health. The seeds have been claimed to stimulate and aid digestion, soothe sore throats, and aid recovery from bronchitis and pneumonia. Having a variety of mustards in one’s food pantry constitutes a good option for reducing calorie intake and improving the taste of the food one should eat.

Mustard seeds contain manganese, iron, magnesium, and selenium. These minerals have anti-inflammatory properties and may relieve the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and asthma as well as reducing the frequency of migraines. The seeds are a source for vitamin B3 and niacin, which may help reduce cholesterol, benefit the auto immune system, improve the skin and hair, and help digestion.

Early mustard plasters were made by spreading a mass of dry mustard seed powder inside a protective covering and applied to relieve pain and supposedly reduce inflammation. A classic description of how these plasters were used and applied may be found in George Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London. Currently, mustard is still used as a topical relief of chronic aches and pains, and even to help with bee stings.

Mustard: Seeds, oil, and the gas

In the medieval days, scattering a few mustard seeds around your house was believed to ward away evil spirits, but there was an evil yet to be uncovered within the seeds themselves. Pressing the seeds of the mustard plant yields an oil popularly used in cooking or as a condiment in countries including China, India, and Russia. However, mustard oil is banned for edible consumption in the European Union, United States, and Canada because of its erucic acid content. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration requires all mustard oil to be labeled “For External Use Only.” It is interesting to note that even in 1390, the manufacture of mustard became regulated and anybody producing a bad mustard was subject to heavy fines.3

|

| Figure 3. Mustard as medicines. Photo taken by Douglas R. Siefken, August 15, 2019. Provided for this article. |

It is important, moreover, not to confuse mustard oil with mustard gas (sulfur mustard), which has nothing to do with mustard chemically, but gets its name from the yellow color and odor of mustard it may develop when combined with other chemicals.6 While not the first war to involve the use of a chemical weapon, World War I was a modern-era demonstration of chemical warfare deployed on a massive and horrific scale. The unfortunate reality is that the mustard gas weapon is still in use and exists in stockpiles around the world. It is relatively easy to produce and was used in the Iran-Iraq War; among those who survived the weapon’s immediate impact, 30,000 still suffered in 2005 from its latent effects which degrade the human condition with cutaneous blisters, respiratory and gastrointestinal tract injuries, eye lesions, organ damage, bone marrow depression, and many other painful residual health issues with its vesicant agent.7,8,9 Even though the gas is rarely fatal, sadly no antidote has been found, but that does not stop modern medicine’s drive to minimize the damage caused by this weapon. Too, from the 1940s, a form of chemotherapy was developed from sulfur mustard and one of its derivatives, showing that a greater good can come despite such an evil.10

Mustard as commerce and a proliferation of recipes

Not to end on dark connotations, this very important plant offers a lot of benefit and happiness; mustard is a desired commodity bringing value to the cycle of commerce. Certainly, the world exports mustard seeds, depending on the type, to markets across the world. Who knew that Canada was a leading exporter of mustard seed, along with Nepal, Myanmar, Ukraine, Russia, China and even the US where Montana and Dakota have its fields.11 When one considers that there are about 1,000 seeds needed to produce an 8-ounce jar of mustard, sales should be good for all the exporters.

Consistent with finding new uses for all types of plant life, so too has there been recent research into varieties of mustards that have a high oil content for use in the production of biodiesel, a renewable liquid fuel. Also, mustard meal can be pressed into an oil to be processed into a pesticide.

But not to go outside of the jar too far, we can conclude that mustard is becoming a condiment of choice with a range of recipes to contribute to health benefits that may potentially improve one’s well-being.

References

- The Mustard Museum. https://mustardmuseum.com/the-mustard-museum/history-of-the-museum/

- Nibble, The History of Mustard. Archived athttps://web.archive.org/web/20200130222837/https://www.thenibble.com/reviews/main/condiments/history-of-mustard.asp.

- The Mustard History. Archived at https://web.archive.org/web/20190917060116/https://www.moutarde-de-meaux.com/en/histo-origine-moutarde.php.

- The Spruce Eats, The History of Mustard as Food. https://www.thespruceeats.com/history-of-mustard-as-food-1807631

- New World Encyclopedia, Mustard. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Mustard

- Hawaii State Department of Health pamphlet. “Sulfur mustard: ‘Mustard gas.’” November 2003. https://health.hawaii.gov/docd/files/2016/12/Sulfur_Mustard_flier_English-1.pdf.

- US National Library of Medicine NIH, Sulfur Mustard Research—Strategies for The Development of Improved Medical Therapy https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2431646/

- Science Direct Medical Aspects of Sulphur Mustard Poisoning https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0300483X05002854

- Medical News Today, What to Know About Mustard Oil https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/324686.php

- War! What Is It Good For? Mustard Gas Medicine. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5325736/

- OEC, Export Data https://oec.world/en/profile/hs/mustard-seeds.

CAROL M. SHERMAN has a Bachelor of Science degree in Biological Science, Major in Political Science, and an MBA in Finance. Currently as President of TransLumen Technologies, she has expertise in advanced technology visualization software applications for observational security, technical simulation training, data visualization, and health and healing digital art. She has also held executive positions as Chief Operation Officer, Chief Administrative Officer, and CFO in Fortune 100 companies, private companies, startups, corporate turnarounds, and managing companies in both growth and recession environments. Additionally, she serves on several not-for-profit boards.

Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 3 – Summer 2020

Leave a Reply