Diana-Andreea Novaceanu

Bucharest, Romania

The history of blood transfusion has unfolded in stages, first from experiments on animals, then from animal to human, and finally to transfusion between humans. The subject, in all its intricacy, has been captured by medical illustrators and painters throughout the centuries. Over the course of the last decades, attitudes towards blood have fluctuated greatly. Events such as the AIDS epidemic have left their mark on contemporary art. There is, however, another expanding direction, that of artists who bring together clinical protocols, medical science equipment, and historical resources. Their works of visual and performance art examine changing attitudes towards blood transfusion.

|

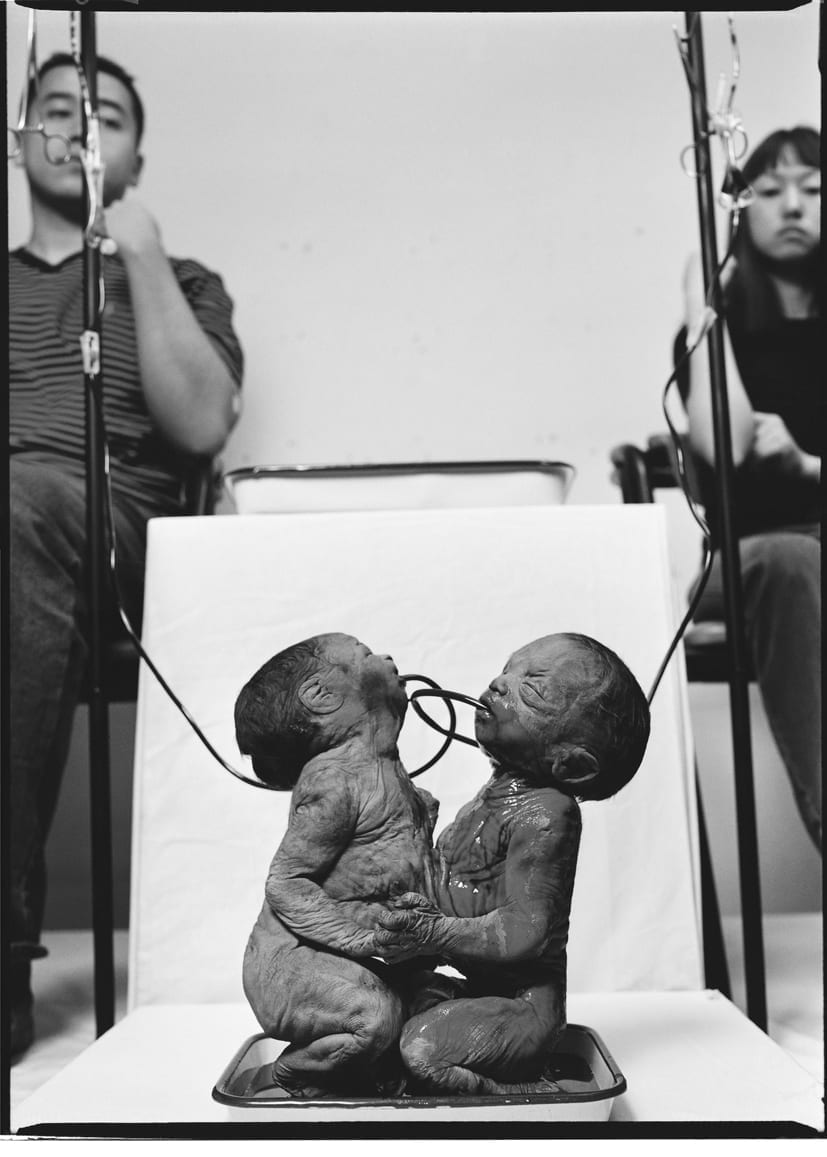

| Sun Yuan and Peng Yu, Body Link performance (2000), photograph taken during the act, obtained directly from the artists. |

Marion Laval-Jeantet, part of the creative duo Art Orienté Objet, was injected with horse blood as part of a 2010 “experiment-performance.”1 Titled May the Horse Live in Me, the action was constructed inside “the interdisciplinary space, linking together different areas of art (mainly body art), scientific research in the field of ethology, immunology, ecology and broadly perceived experimentation.”2 Scenes included the artist receiving immunoglobulin to minimize the risk of an anaphylactic reaction. A horse was then led inside Ljubljana’s Kapelica gallery and Laval-Jeantet walked towards it using special braces equipped with hooves. Emergency medical personnel were on standby throughout the performance and afterwards completed a physical examination.

The artist described her state as “extra-human”3 following the transfusion. Laval-Jeantet recounted feeling “hyper-powerful, hyper-sensitive, hypernervous, and very diffident. The emotionalism of a herbivore. I could not sleep. I probably felt a bit like a horse.”4 Her performance reflects early modern concerns about transfusion of blood between species, as well as the ethical and theological implications of performing such an act between an animal and a human.

Another reimagining of xenotransfusion is offered by Revital Cohen. As part of her Life Support project in 2008, Cohen designed a genetically modified sheep to be connected to a patient at night in order to use the animal’s kidneys as a natural filtration system such as in hemodialysis.5 The transgenic sheep, born out of the human’s need and tailored to its genome, grazes on grass during the day, and enjoys a carefree existence. The health of the human depends on that of its transfusion partner. Such reimagining is an emphatic departure from the first documented animal transfusions and xenotransfusions performed by Richard Lower and Jean-Baptiste Denys.

By the early nineteenth century, blood transfusions had become “discredited and almost forgotten in both Europe and America.”6 It was in 1818 that James Blundell performed a successful transfusion of human blood on a woman rapidly deteriorating from a severe postpartum hemorrhage. He had been stirred by the frequent cases he had witnessed as a young physician. Having performed extensive animal experimentation, Blundell came to the conclusion that only blood from a donor of the same species as the recipient would be safe for use. The episode marked “the beginning of the modern era of transfusion medicine,”7 which would further develop after Karl Landsteiner’s 1901 discovery of the ABO blood group system.

In 2011 Paul Craddock staged a performance in London’s Trafalgar Square using approximations of the transfusion equipment employed by James Blundell. The cultural historian of medicine introduced the curious passersby to the Impellor, a piece of equipment made out of a cup to collect pooling blood and connected to a tube and a syringe; as well as the Gravitor, a device used to inject blood. Another performance was Body Link (2000) by conceptual artists Sun Yuan and Peng Yu. The pair transfused one hundred centiliters of their own blood into a medical specimen of abdominally conjoined fetal twins. In photographs taken during the show, the artists sit on either side of a table with blood tubing connecting their arms to the mouths of the twins where it overflows, drenching the bodies. The performance is strongly tied to Chinese ideals of personhood and generational duties. It is also a testimony to the status transfusion has obtained in contemporary visual culture. The thin, red lines that frame this startling family portrait depict how metaphorical blood lines have become real, palpable objects.

|

| Marc Quinn, Self 1991, from the artist’s website, with permission from the artist, location unknown. |

Blood has been used as a material by several leading artists such as Andres Serrano, Herman Nitsch, and Lani Beloso. In some cases, this involved more than integrating it among more traditional media, but also included the subject of transfusion science as a fundamental element of the artistic process. This experimentation becomes a metaphorical transfusion between the creator as donor and the viewer as recipient.

Marc Quinn’s ongoing series Self is an example of disarmingly personal portraiture made possible only by modern transfusion practices. The forerunner Self (1991) is crafted out of eight pints of the artist’s blood, collected over one year, then set into a mold of Quinn’s head and kept frozen inside a Plexiglass case. The sculpture records in minute detail the physical transformation brought about by aging, with a new model produced every five years. A posthumous cast is scheduled to be made with blood extracted from the artist’s deceased body and set inside a death mask. The existence of the work is possible because of processes commonly employed by blood banks. The mold of Quinn’s head is dependent on its encasement, and is “visually and conceptually essential”8 in maintaining a vivid “portrait of mortality.”9

In the case of Vincent Castiglia, blood is used as the exclusive material for figurative, allegorical paintings. An essential step in the artistic process is the collection of blood through repeated bleedings in what the artist describes as a “very controlled and clean process” that has been perfected over the years. Castiglia recalls his early difficulties with rapid coagulation, an issue that historically factored heavily in the capability for blood transfusions. Developed by Joseph Kleiner in 1947,10 Vacutainer tubes have made “its collection and handling easy and reliable” for the painter. Castiglia sometimes considers his work to be “not paintings, they are hemorrhages.”11 Blood has not lost its connection with strong, powerful emotions.

There is a growing amount of artwork that draws from medical history, highlighting forgotten perspectives and inherent biases connected to practices of transfusion. While a number of artists have begun to explore “the need for another, non-hierarchical, non-anthropocentric relationship between humans and animal,” others delve into the ethics of early experiments. The names of Arthur Coga, Antoine Mauroy, and many unnamed human subjects that have contributed to the development of blood transfusions are now being rediscovered and rehabilitated through works of literature, visual arts, and performance.

Blood unites and divides. There is growing arts-based research about the ways that race, gender, and class have contributed to historical representations, and an increasing number of artists who bring new, previously marginalized perspectives to this fundamental aspect of modern medicine.

Endnotes

- Aleksandra Hirszfeld,May the Horse Live in me (interview with Art OrientéObjet), Art+ Science Meeting, http://laznia.nazwa.pl/artandscience_wp/?page_id=306&lang=en, (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Robert Zwijnenberg, On Xenotransfusion and Art, p. 134 in AssiminaKaniari, From Institutional Critique to Hospitality: Aspects and Contexts of Bio Art, Grigori Publications, 2015

- Paul L. A. Giangrande, The history of blood transfusion, British Journal of Hemathology, 2001, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02139.x (accessed 15 January 2020)

- Ibid.

- James Romaine, Marc Quinn: The Matter of Life and Death, Image Journal, Issue 69 , https://imagejournal.org/article/marc-quinn-matter-life-death/ (accessed 14 January 2020)

- Ibid.

- Louis Rosenfield, A Golden Age of Clinical Chemistry: 1948-1960, Clinical Chemistry, vol. 46, no. 10, 2000, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.546.5431&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 10 February 2020).

- Lily Streeter, Blood on Canvas, Animal New York, 2012, http://animalnewyork.com/2012/mixed-media-blood-on-canvas/ (accessed 11 February 2020).

References

- Craddock, Paul, The Cultural History of Transplantation, https://paulcraddock.com/cultural-history-of-transplantation/, (accessed on 10 January 2020)

- Hirszfeld, Aleksandra, May the Horse Live in me (interview with Art OrientéObjet), Art+ Science Meeting, http://laznia.nazwa.pl/artandscience_wp/?page_id=306&lang=en, (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- Streeter, Lily , Blood on Canvas, Animal New York, 2012, http://animalnewyork.com/2012/mixed-media-blood-on-canvas/ (accessed 11 February 2020).

- Romaine, James, Marc Quinn: The Matter of Life and Death, Image Journal, Issue 69 , https://imagejournal.org/article/marc-quinn-matter-life-death/ (accessed 14 January 2020)

- Rosenfield, Louis, A Golden Age of Clinical Chemistry: 1948-1960, Clinical Chemistry, vol. 46, no. 10, 2000, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.546.5431&rep=rep1&type=pdf (accessed 10 February 2020).

- Zwijnenberg Robert (2015) On Xenotransfusion and Art, p. 134 in AssiminaKaniari, From Institutional Critique to Hospitality: Aspects and Contexts of Bio Art, Grigori Publications

DIANA-ANDREEA NOVACEANU, MD, MA, is a Cultural Studies PhD candidate at the University of Bucharest (UB). Her research interests lie in the interactions and intersections of clinical practice and contemporary visual arts, with a focus on creative expressions of the Foucaultian medical gaze. Diana holds an MA in “Image Theory and Practice” from the Centre of Excellence in Image Studies (UB). Parallel to her academic career, she has been completing her residency in Epidemiology and Hygiene. Diana is a contributing writer for Synapsis: A Health Humanities Journal and independent curator.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply