Ariana Shaari

New York, New York, United States

|

|

Figure 1. Life of the Virgin 4: The Birth of the Virgin. Alfred Durer. 1503, Woodcut, Staatliche Graphische Sammlung, Munich. Source |

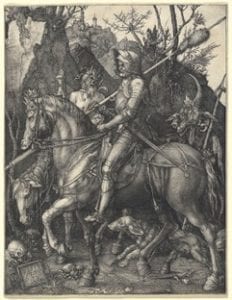

Albrecht Durer is considered one of the masters of German Renaissance art and has been dubbed “the da Vinci of the North.” He is especially esteemed for elevating printmaking to an art form and for deeply psychological and technically impressive works on religious subjects such as Life of the Virgin and Meisterstiche (Figure 1, 2).1

Durer was highly influenced by Italian Renaissance art and theory. During visits to Italy in the early 1500s, he dove into studies of human anatomy and wrote Four Books of Human Proportion.2 Durer spent time in Padua, which was a hub of European medicine. This allowed him to observe sick people and study their illnesses.3

|

| Figure 2. Meisterstiche, The Knight. Alfred Durer. Source |

Previous scholars have analyzed Durer’s work through a medical lens. In his article “Hydrocephalus(?): Albrecht Durer, 1506,” physician Leon Goldman argues that in the drawing Heads of Children, Durer investigates nasal deformities and explores his interest in “scientific studies of the proportions of the human body” to such a high level of detail that “the pediatrician or the student of anthropology will have to decide whether hydrocephalus is present.”

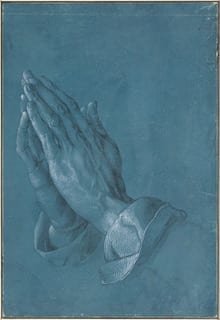

One of Durer’s works that explores the human form is Praying Hands, made in 1508 in Vienna (Figure 3).

The piece’s intended function is highly debated. Some scholars believe it is an early sketch intended for the Hellar Altar, but a more generally accepted theory is that it was meant to showcase his technical talent. Christof Metzger, a renowned scholar, points out research that suggests that the hands are actually Durer’s, and this work is a self-portrait.4 On further investigation into Durer’s life and artistic interests, Praying Hands becomes not just a showcase of Durer’s talent, but also an exquisite depiction of arthritis.

|

| Figure 3. Praying Hands. Albrecht Durer. 1508. Drawing. Albertina, Vienna |

With this in mind, a few notable characteristics are worth discussing. The hands are clasped nearly perfectly together, with extreme care and precision taken to detail the vasculature, nail beds, and delicate workings of the skeletal system under the surface of the carefully contoured skin. The fifth finger on the right hand is not extended in the same manner as the other digits. The diagnosis of arthritis in the painting has even been suggested to be a subtle symptom of diabetes mellitus, in which the patient is not able to fully clasp hands together because of joint immobility. Limited joint mobility, or diabetic cheiroarthropathy, is hand stiffness that results from tightened skin and flexion contractures.5 A diagnosis of diabetes could help explain why the person depicted is unable to fully extend the joints.

While evidence for a diagnosis of diabetes specifically is not supported by strong historical or artistic evidence, the case for arthritis is. Previous scholarly work has demonstrated that later in his life, Durer suffered from arthritis in his hands.6 By careful analysis of depictions of Durer’s family members, many of whom were artists themselves, one notes clear depictions of joint swelling typical of arthritis. Arthritis is also seen in sixteenth century engravings and paintings in three members of the Durer family.7

Did Durer intend for this to be a depiction of his own arthritis? We do not know, and we should be cognizant of the pitfalls and dangers of making a diagnosis in retrospect. But putting together Durer’s own art, his family history, and previous scholarly work, makes Praying Hands an important painting of a Renaissance master who had an interest in human anatomy and perhaps suffered from that medical condition himself.

Endnotes

- History, H. T. o. A. Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/durr/hd_durr.htm

- (History)

- Praying Hands. Retrieved from http://www.albrechtdurer.org/praying-hands/ Sharma, P. (1997). Medicine, Dürer, and the praying hands. The Lancet, 349.

- Praying Hands. Retrieved from http://www.albrechtdurer.org/praying-hands/

- (“Limited Joint Mobility in Diabetes Mellitus: The Clinical Implications,” 2011)

- Albrecht Dürer – Biography and Legacy. Retrieved from https://www.theartstory.org/artist/durer-albrecht/life-and-legacy/

- Clinic, M. Arthritis. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/arthritis/symptoms-causes/syc-20350772

ARIANA SHAARI is a senior at Barnard College, Columbia University majoring in psychology. Her love of literature and art history fuels her pursuit of a career in medicine.

Winter 2020 | Sections | Art Flashes

Leave a Reply