Safia Benaissa

Mostganem, Algeria

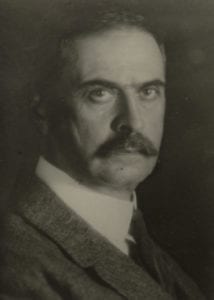

Karl Landsteiner was the Austrian scientist who recognized that humans had different blood groups and made it possible for physicians to transfuse blood safely. He entered medical school at the University of Vienna, where he developed an interest in chemistry. After taking off a year to complete his military service he returned to finish his studies and received his M.D. in 1891 at age twenty-three.

He subsequently worked in the laboratories of the greatest chemistry specialists of his time, publishing many papers with them and developing an interest in immunology. Working in Vienna between 1897 and 1920, first as assistant and later as associate professor, he carried out studies on poliomyelitis, showing it was infectious and isolating its virus.1 In 1900 he began to test the sera and red cells from the scientists working in his laboratory, including his own, showing that blood from certain scientists caused the blood of others to clump, and postulating the existence of at least two blood groups. He published a paper that first mentioned agglutination of human blood and proposed that this was linked to the uniqueness of an individual’s blood rather than having a pathological cause. This valuable conclusion led to the identification of the four blood groups.

He then discovered that the cause of agglutination was an immunological reaction in which the host produced antibodies against donated blood cells. This immune response is elicited because blood from different individuals may vary in certain antigens located on the surface of red blood cells. Landsteiner identified three such antigens, which he labeled A, B, and C (later changed to O). A fourth blood type, later named AB, was identified the following year. He found that if a person with one blood type—A, for example—received blood from an individual of a different blood type, such as B, the host’s immune system will not recognize the B antigens on the donor blood cells and thus will consider them to be foreign and dangerous.

To defend the body from this perceived threat, the host’s immune system will produce antibodies against the B antigens, and agglutination will occur as the antibodies bind to the B antigens. This discovery laid the groundwork for the first successful blood transfusions and also suggested other uses for his findings, such as in paternity cases or solving crimes if blood stains were left on the scene.2

He also pioneered the use of dark-field microscopy to detect the spirochetes of syphilis and studied human-to-animal transmission, hoping to find antibodies to the disease. His examination of these antigen-antibody reactions ultimately led him to explore the chemical and immunological basis of skin sensitization and allergy.3 Moving after World War I first to the Netherlands and then to the United States, he worked with Philip Levine to discover in 1927 the M, N, and P factors blood factors.4 But he considered his greatest work to be his investigation into antigen-antibody interactions, which he carried out primarily at Rockefeller Institute in New York City (1922–43). In this research he used small organic molecules called haptens—which stimulate antibody production only when combined with a larger molecule such as a protein—to demonstrate that small variations in a molecule’s structure can cause great changes in antibody production.

Landsteiner retired officially in 1939, but worked with Alexander Wiener to discover the Rhesus (Rh) factor in 1940, supplying the “pathophysiological basis for erythroblastosis” and illustrating the relationship between a mother and a fetus’s blood types and antibodies. He also worked with the Romanian bacteriologist Constantin Levaditi on poliomyelitis and laid the groundwork for the development of a polio vaccine. After years of work, at the age of seventy-five Karl Landsteiner had a heart attack in his laboratory on June 24, 1943 and died two days later6 in the same hospital where he had done such distinguished work.5 His discovery, which won him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1930, made blood transfusion a life-saving medical practice and saved many lives. In the 1800s doctors knew that transfusing blood between individuals could cause red blood cells to clump, a phenomenon called agglutination. But they did not know why, and it was Landsteiner who showed that agglutination is a response of the immune system.

References:

- https://www.healio.com/hematology-oncology/news/print/hemonc-today/%7Bf3e8beac-8565-4919-bd91-34b9b3b78c64%7D/karl-landsteiner-discovered-the-four-blood-groups

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Karl-Landsteiner.

- https://www.healio.com/hematology-oncology/news/print/hemonc-today/%7Bf3e8beac-8565-4919-bd91-34b9b3b78c64%7D/karl-landsteiner-discovered-the-four-blood-groups.

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Karl-Landsteiner

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6077641/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6077641/.

SAFIA BENAISSA graduated from the French media and the communication license in 2015 and completed her master’s education in 2017. While she has teaching experience, Safia is an aspiring journalist from Algeria.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply