Cristina Sans-Ponseti

Barcelona, Spain

Nowadays, it is usual to see donation centers storing blood worldwide. Blood banks meet the demand for blood in order to perform transfusions and produce plasma-based products.1 The use of blood in industrial processes resulted from historical and social contingencies. Our knowledge of the human body, including blood, has changed substantially, along with the medical paradigms that shaped it.

For centuries, blood was conceptualized by Galenic medicine as one of the four basic humors that made up our bodies. Being healthy meant keeping those humors in balance and lead to the practice of bloodletting, the longest-running technique in medicine.2 In the seventeenth century, blood was seen anew as a fluid pushed by the laws of mechanics and physics.3 The use of microscopes during the next century allowed physicians to investigate the internal structure of blood, a liquid tissue of cells suspended in plasma. Yet the industrial turn only took place over the last hundred years and was propelled by two World Wars and the birth of the Red Cross. Blood became a medicine and a raw material following the introduction of industrial capitalism into the medical sciences. A modest laboratory in Barcelona, eventually becoming a leading multinational company, has played a key role in this transformation.4

In 1909 three young physicians from a newly educated medical class of Barcelona established the Instituto Central de Análisis Clínicos.5 Doctors Luis Celis, Ricard Moragas, and Josep Antoni Grifols-Roig belonged to an internationally well-connected generation intent on modernizing the discipline.6 Their practice emerged from a scientific culture that led to the formation of new medical specialties, the consolidation of urban medicine, and the introduction of analytical methods of diagnosis.7 The Instituto carried out biological research with state-of-the-art technologies and performed clinical tests on blood, feces, and urine.8 Their clients hired them to investigate the bacteriology of samples: serodiagnosis for Mediterranean fever, Wassermann’s reaction for syphilis, or hemocultures. This was the birth of modern hematology, which used technology to extract information that could not be obtained directly by exploration. Sterility was a challenge and samples were often contaminated. New technical devices were therefore devised, allowing absolute asepsis. Grifols-Roig would later improve and patent them under the name of flebula aspiradora.9

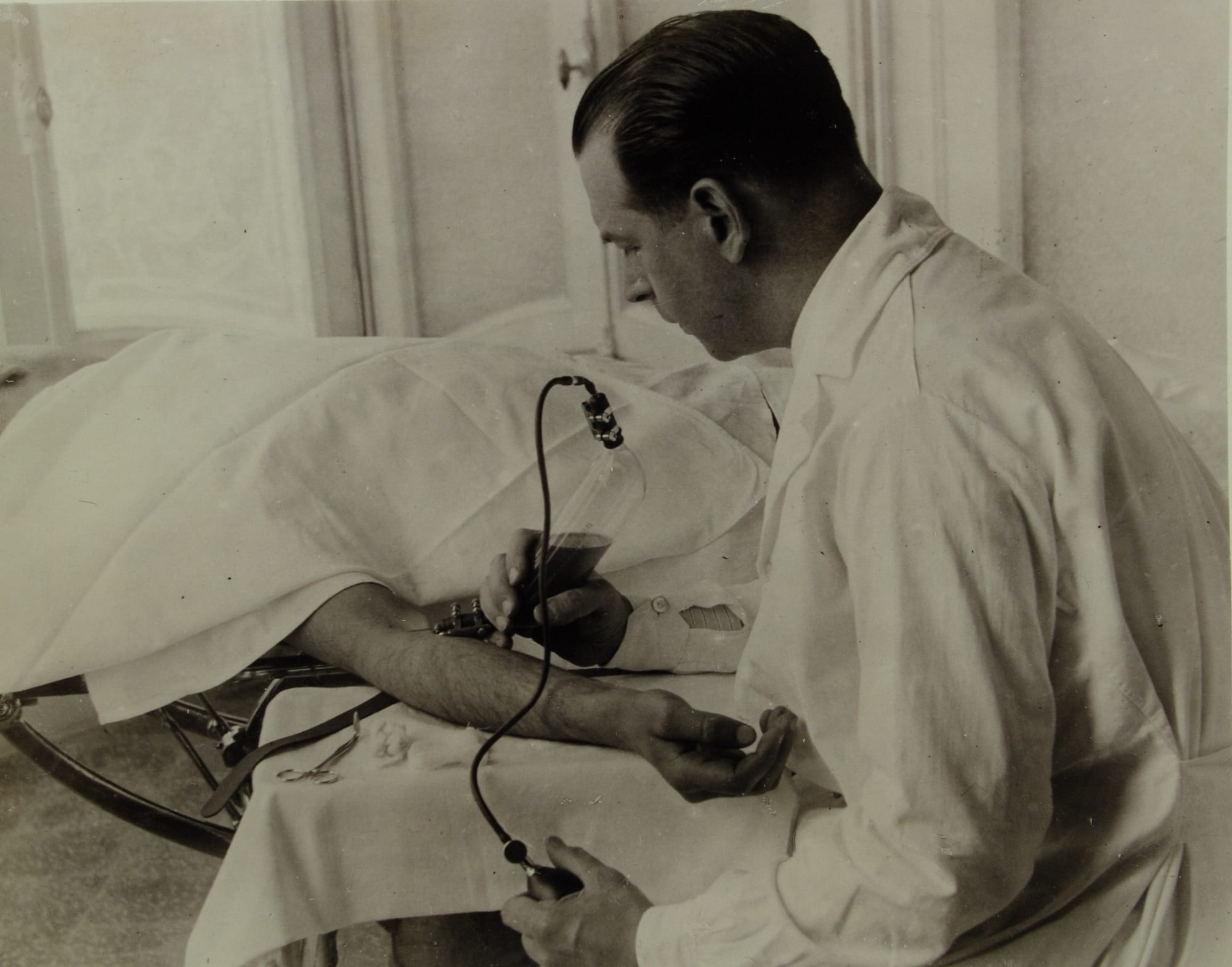

These innovations built on the discovery of the existence of blood groups by Karl Landsteiner in 1901, the development of new devices for safer blood extraction and injection, and the use of sodium citrate as an anticoagulant substance by Luis Agote in 1914.10 The Great War was a testing ground for large-scale blood transfusions, and in the interwar years the practice was extended to civil society.11 A promising discipline was emerging: hemotherapy, or the study of the therapeutic value of blood. Many realized that potential. In 1921 Percy L. Oliver, secretary of the Camberwell Division of the British Red Cross Society, organized the first typified donors list. The London Blood Transfusion Service (LBTS) became the first public entity of voluntary donors.12

In Barcelona, the physicians of the Instituto brought their expertise in hematology to blood transfusions. In 1923 the three partners split and the Instituto was moved to a larger facility in the scientific swarm of Barcelona’s Eixample under the lead of Grifols-Roig.13 In 1925 he began to attempt indirect blood transfusions,14 and three years later he patented the first device in Spain to carry them out, the flebula transfusora.15 He already knew how to store blood in sterile conditions for analysis, so he only had to develop his own device to fulfill a new demand: a way to store sterile blood for transfusion.16 Grifols-Roig also tried to organize the first donors list of Barcelona, analogous to LBTS.17 Until 1934 the three largest public hospitals in Barcelona required its services. Meanwhile, Celis became a full professor of histology and anatomical pathology at the University of Barcelona, where “young students learned with him to look under the microscope.”18 The third partner, Moragas, worked as an analyst at the Laboratories of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau (HSCSP), where in 1930 he became director and two years later founded the first Blood Transfusion Service of the hospital together with Dr. Manuel Miserachs. Moragas received honors from the German Red Cross and Miserachs would become an outstanding member of the Spanish Red Cross.19

The Spanish Civil War would change their lives and the history of hemotherapy. In October 1936, shortly after the onset of the war, hematologist Frederic Duran-Jordà, head of the Blood Transfusion Service of the Republican Government, created one of the first blood banks in the world. The Blood Transfusion Service in the Front (BTSF) was an effective system for storing classified non-coagulated blood, collected from voluntary donors in Barcelona and sent to the front in refrigerated trucks. Moragas and Miserachs belonged to Duran-Jordà’s team,20 as well as the two sons of Grifols-Roig, the physicians Josep Antoni and Victor Grifols-Lucas.21 The therapeutic power of blood exploded as, for the first time, it could be safely extracted and used away (both spatially and temporarily) from the body that contained it. After the war blood became an injectable medicine, with a well-established scientific basis for its administration. Blood typing established compatibility, anticoagulant methods set the format for transfusion, and blood became available continuously thanks to the logistics developed by the BTSF.

The pace intensified during the Second World War. Western countries made their transfusion services into blood banks as modeled by the BTSF. The blood needed for troops would now come from the civilian population22 and became a strategic element of the war arsenal. In Britain, an exiled Duran-Jordà reproduced BSTF with Janet Vaughan, which gave English physicians access to a supply of blood for transfusion. In the Soviet Union, Dr. Yudin led the creation of blood banks and established more than 1,500 donation centers all over the country. The United States, facing the problem of shipping blood across the ocean, focused on plasma research23 and introduced the lyofilization and fractionation of plasma. They adapted laboratory procedures to industrial production, but these technologies required far more blood than what was needed for mere transfusion. To avoid production depending on human donation, they tried to produce a synthetic substitute without success. In the end, the American Red Cross covered its needs through the collection of an unprecedented amount of blood.24

The implementation of large-scale industrial methods made blood a strategic product, with plasma becoming the key element. Again Barcelona’s hemotherapists took the lead. Miserachs led the Blood Transfusion Service of the Red Cross of Barcelona during the 1940s, and in 1962 founded the Blood Bank of Barcelona.25 For seventeen years, he ran a public institution concerned with the voluntary collection of blood, as well as its storage and distribution, a work for which he was distinguished with the Silver and Gold Medals of the Spanish Red Cross. Meanwhile, the Grifols family founded Laboratorios Grifols S. A, the predecessor of the multinational company. They introduced the lyophilization method to Spain in 1943, and created one of the first lyophilizers of Europe.26 Two years later, they opened the Hemobanco, one of the first private blood and plasma banks in Spain.27

As Douglas Starr has put it, “The story of blood is one of metamorphosis, of a liquid that became symbolically transformed as society learned how to deconstruct and manage it.”28 Blood exemplifies a change in perspective from a “magic” fluid to a high-tech laboratory product, medicine, and raw material capable of feeding a global industry.

References

- World Health Organization Blood Transfusion Safety, The Clinical Use of Blood (Geneva: WHO, 2002), 22.

- Douglas Starr, Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998).

- José María López Piñero, Historia de la medicina (Madrid: MELSA, 1990), 66.

- We can perform this investigation thanks to a collaboration between Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (UAB) and Grifols, S.A.

- Grifols Historical Archive, Laboratorio de investigaciones Biológicas (Barcelona: Instituto Central de Análisis Clínicos, 1908, Reference MG0453).

- Alfons Zarzoso and Àlvar Martínez-Vidal, “Laboratory medicine and surgical enterprise in the medical landscape of the Eixample district” in Barcelona: An Urban History of Science and Modernity, 1888–1929, ed. Oliver Hochadel and Agustí Nieto-Galan (Barcelona: Routledge, 2016), 69-72.

- Alfons Zarzoso, “Medicina i cirurgia en temps de guerra” in Història mundial de Catalunya, ed. Borja de Riquer (Barcelona: Edicions 62, 2018), 762-769.

- Paloma Fernandez and Ferran Sabaté, “Entrepreneurship and management in the therapeutic revolution: The modernisation of laboratories and hospitals in Barcelona, 1880 – 1960”, Investigaciones de Historia Económica, no. 15 (2017): 91-101.

- Grifols Historical Archive, Flebula aspiradora Grifols: aparato para extraer automáticamente sangre y otros fluidos del organismo humano y animal destinados al análisis (Barcelona: Sociedad General de Farmacia, 1928, References MG0761, MG6495 and MG2054).

- Miquel Lozano-Molero, “Passat i actualitat de l’obra de Frederic Duran Jordà”, Reial Acadèmia Mèdica de Catalunya, no. 21 (2006): 66-67.

- William H. Schneider, “Blood transfusion between the wars”, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, no. 58 (2003): 187-224.

- Douglas Starr, Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998).

- Grifols Historical Archive, Memoria del Hemobanco (Barcelona: Laboratorios Grifols, S.A. 1953, References MG6353).

- Paloma Fernandez and Ferran Sabaté, “Entrepreneurship and management in the therapeutic revolution: The modernisation of laboratories and hospitals in Barcelona, 1880 – 1960”, Investigaciones de Historia Económica, no. 15 (2017): 91-101.

- Josep Antoni Grifols-Roig, “La transfusió de sang citratada per mitjà de la flèbula transfusora,” Annals de l’Hospital Comarcal de Vilafranca del Penedès, 49-65.

- Josep Antoni Grifols-Roig, “Blood transfusion apparatus”, Invention patent from the United States Patent Office.

- Josep Antoni Grifols-Roig, “Cos de donants per la Transfusió Sanguínia”, La Vanguardia, August 5, 1928, 32.

- Alfons Zarzoso, “Lluis Celis i Pujol”, Galeria de Metges Catalans, accessed January 7, 2020, https://www.galeriametges.cat/

- Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau Archive, Libros mayores (Barcelona: Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, 1948).

- Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau Archive, Libros mayores (Barcelona: Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, 1949).

- Grifols Group, Dedicado a la vida: Grifols, 60 aniversario (Barcelona: Grupo Grifols, S.A., 2001).

- William H. Schneider, “Blood transfusion between the wars,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, no. 58 (2003): 187-224.

- Douglas Starr, Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998).

- Douglas Starr, Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998).

- Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau Archive, Libros mayores (Barcelona: Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, 1948).

- Grifols Historical Archive, El plasma liofilizado (Barcelona: Laboratorios Grifols S.A., 1953, References MG0581).

- Grifols Group, Dedicado a la vida: Grifols, 60 aniversario (Barcelona: Grupo Grifols, S.A., 2001).

- Douglas Starr, Blood: An Epic History of Medicine and Commerce (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1998), 54.

CRISTINA SANS-PONSETI, BSc, MSc, MA, is a second year Industrial PhD student in History of Science (CEHIC-UAB), in collaboration with Grifols, S.A. In her dissertation called Medical industrialization: The rise of Laboratorios Grifols and the development of hemotherapy. Science, industry and technological innovation in Catalonia (1931-1959), she is studying the rise of Laboratorios Grifols, from a modest practice in Barcelona to a major multinational pharmaceutical company, trying to investigate how the small-scale scientific practices become industrialized processes that could be described more accurately as Big Science methods.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply