Bahar Dowlatshahi

Tehrann, Iran

Blood is believed to have special abilities and properties in many eastern countries such as Iran. Even human personality traits, emotions, and relationships are referred to with blood. Angry people boil their blood; those who are kind and loving are called warm-blooded. In the tradition of some tribes, a stranger can be a sister or a brother by mixing a small amount of blood. It is said that if a father had never seen his child’s mother, he would always know her because their blood would pull them together. These beliefs and customs demonstrate the importance of blood for the people of this land.

In ancient times many tribes drank the blood of brave, beautiful, and intelligent human beings so that these traits would flow into their blood. In Iranian folk culture, human blood can be the source of many diseases and pollutants, so it must be kept clean. Purity of blood is believed to bring about good health to all parts of the body. Pure blood also brings about the mental health of the soul, which can be traced back to eastern mysticism.

In Iran, there are some interesting ways to purify the blood for a healthy body and mind. Medicinal herbs, natural foods, and certain fruit juices are used to cleanse the blood. Some are prescribed by doctors. Others have been traditionally used in families since ancient times, and are sometimes the main foodstuff. Fruits to cleanse the blood include lemongrass, grapes, oranges, grapefruits, pineapples, berries, kiwi, and strawberries. Raw vegetables such as garlic, onions, carrots, celery, parsley, sprouts, and soybeans are also used. Sprouts are used to enhance desserts, and traditional spirits and juices such as cherry, barberry, and pomegranate are also consumed for this purpose.

Another way to purify the blood is through blood donation. People find this work to be good and benevolent because it helps people who are sick, and is also good for the health of the donor. It is believed that removing a small amount of blood regenerates a young and vibrant blood supply that recharges the body, heart, and brain. Although there is no evidence for this, no scientific authority counters this thinking because it increases the amount of blood donations.

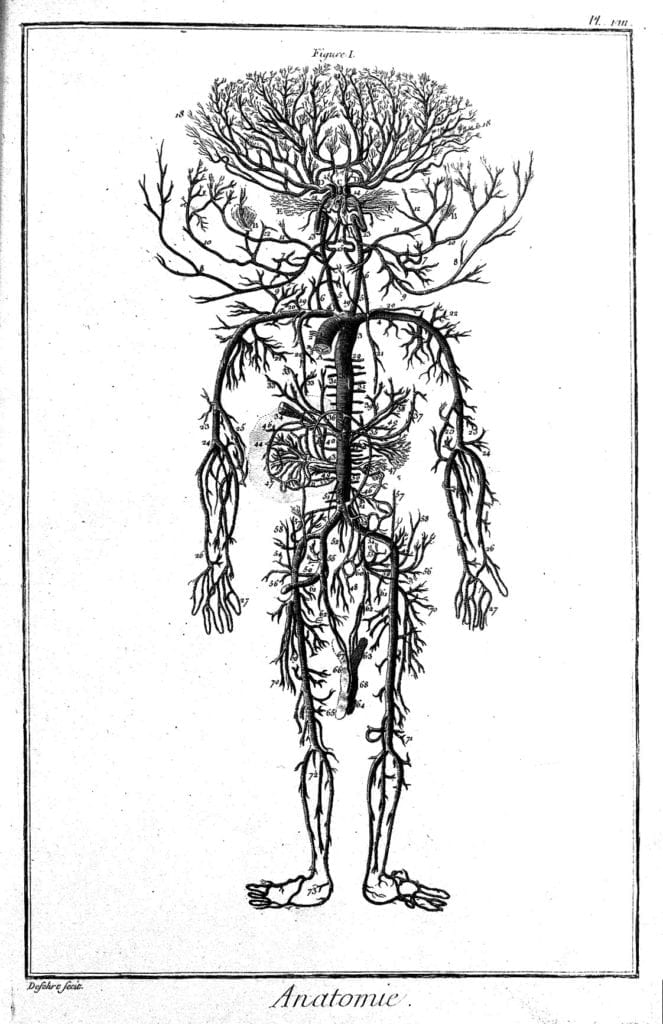

Besides blood donation, there are other popular methods for blood purification that are highly specialized. Each method is a type of bloodletting that has been named for its form: lacquering, cupping, and percentage. In ancient times, bloodletting was performed to remove the devil from the body of sick people. Later, bleeding was used as a way to achieve balance among the bodily humors. The Egyptians were probably the first people to use a razor blade for bloodletting, but the practice peaked in the Hippocratic era. In Galen’s writings there is also discussion of cupping.

Cupping is an outpatient procedure, using a device called a glove that swells and then scrapes the surface of the skin to drain unhealthy or dirty blood. The best time for general cupping is in the spring. Traditional medicine believes that during this season, with the outflow of old blood, the body becomes breathable and fresh like the ground. It also strengthens vigor and prevents disease. General cupping usually occurs between the two scapulae and may be superficial or deep, depending on the examination of the traditional physician. Specific cupping is used for patients with congenital problems or a diagnosed disease in a specific area of the body. However, cupping is forbidden in pregnant women, infants, and patients with hemophilia or thalassemia. In Iran, cupping is used to treat many conditions including headache, addiction, high blood pressure, acne, allergies, heart attacks and strokes, back and joint pain, asthma, neurological conditions, mental illness, kidney and gallbladder stones, hepatitis, and some types of cancer.

Another method of bleeding called percentage is a type of venous blood sampling on the outside of the elbow, inside the elbow, on the left and right lower limbs, under the tongue, behind the knee, behind the foot, and behind the ear. The practitioner creates a small groove, then catches the dirty blood in a container. Most practitioners today do not open the vein, but draw blood through a syringe instead.

The use of leeches for bloodletting dates back 2000 years to the sages of India, Egypt, Iran, Rome, and other parts of Europe. Ibn Sina and Hakim Jarjani discussed the benefits of leeches for the treatment of skin diseases, and Ibn Sina even spoke of the types of leeches that should be used. Leeches today are used to treat conditions such as arthritis, vascular disease, headaches, chronic pain, gastrointestinal problems, gynecological disorders, depression and anxiety, and others. The placement of the leeches varies according to the disease. Leeches contain an anticoagulant substance called hirudin, which dilutes blood and opens the veins, thereby increasing circulation, especially on the surface of the skin.

According to some experts, other substances with therapeutic effects are released into the blood by leeches. This has attracted the attention of physicians in many parts of the world for use in cases of coronary artery bypass grafts, skin grafts and cosmetic surgery, and organ transplants. Leeches are also used to strengthen the body’s immune system.

The paddy fields and marshes in the northern provinces of Iran are a good place to find leeches in their natural habitat. However, this carries a risk of bacteria and viruses. Today leeches for therapeutic use are raised in sterile conditions. Breeding leeches has become profitable in some countries in Asia and Europe.

Bloodletting in its different forms has ancient roots in countries such as Iran. There is some modern evidence that some of these ancient traditions may still have a place in medicine to promote a healthy mind and body.

BAHAR DOWLATSHAHI lives in Tehran, the capital of Iran. When she was 18 she served as a paramedic during the war in the 1980s. The war fascinated her with medical science, but her spirit was drawn to art, and she studied script writing at university. After working as a screenwriter and director she began writing a book, the first of which was published in 2018, with two more forthcoming. She has a great interest in research and the scientific history of her country.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply