Rhianna Elliott

Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom

Bloodletting, also known as “phlebotomy,” was a common preventive and therapeutic medical practice in early modern England. Its theoretical foundation was in humorism, the ancient medical system where bodily health depended on the balance between four fluid humors (blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile). Yet even amongst lay people with little or no knowledge of medical doctrine, the cessation of the flow of fluids was thought to cause disease; bloodletting evacuated excess blood humor to cure sickness and restore health. Today, blood remains essential to the improvement and preservation of bodily health. In modern Western medicine, where reintroducing blood into bodies via transfusions and dialysis are common and crucial practices, the idea that we might sustain life through its permanent removal appears incongruous. As late as the nineteenth century though, patients and practitioners opened veins all over bodies to treat or prevent a broad spectrum of diseases, from falling sickness (epilepsy) to plague. Early modern medical texts often recommended bloodletting to treat menstrual disorders. Women who suffered from menstrual disorders bled irregularly, which threatened their capacity to bear children—an important marker of female social status in post-Reformation Protestant England.

Menstruation was essential to the general health of female bodies. A build-up of menstrual blood formed a thick, putrefying mass, generated noxious vapors, and corrupted the womb. The retention of menses was a primary sign of menstrual disorders such as suffocation of the womb (hysteria) and green sickness. To prevent or cure these disorders and restore women’s health and fertility, texts recommended bloodletting to encourage the return of the natural menstrual flow. In her 1671 manual The Midwives Book, seventeenth-century midwife Jane Sharp taught that “Diseases [of the womb] grow when they are stopt by thick blood” so remedies encouraged the movement of blood.1 Bloodletting was not the only therapy used to reinstate blood flow—medical texts also recommended herbal remedies, pessaries, or aromatic fumes directed into the womb—but it was arguably the quickest and most effective. Likewise, menstrual disorders were by no means the only malady treated with bloodletting, but they provide a great case study to demonstrate the physics and philosophy underpinning the practice of phlebotomy in the early modern period.

Natural vs artificial bleeding

In the premodern world, menstruation was a mysterious natural phenomenon. To most observers, it was a natural process that evacuated excess, sometimes harmful, matter from bodies, but there was some disparity concerning this definition amongst learned men. Elite medical writers drew on ideas about sex, pathology, and natural philosophy to debate technical theories about the physics of menstrual bleeding.2 Some writers treated menstruation as a dangerous, pathological condition, citing Pliny the Elder’s Natural History (77 AD) and the Book of Leviticus.3 But by the seventeenth century, menstrual blood no longer had the capacity to tarnish mirrors, compel penises to fall off, or force dogs into madness. Instead, much emphasis was placed on its role as a natural life-giving substance tied to health and fertility. Although male hemorrhoidal bleeding was also considered a form of menstruation, it was mostly perceived as a feminine faculty, where the periodic expulsion of blood from the womb was necessary for healthy procreation and general humoral balance.4

The practice of bloodletting was very similar to menstruation as it mimicked the naturally therapeutic process of evacuating superfluous matter from bodies. The key difference was that bodies had natural orifices created with the intent to expel matter. As a form of therapy, however, artificial bleeding was considered just as valid as these natural physiological processes. The practitioner was Nature’s helper and their intention was to unblock the body of slow, stagnant blood so that its ordinary course was restored. In this case, if menses were not released naturally from the womb at regular periodic intervals, they could be drawn out through a carefully scheduled and positioned incision.

Rules for bloodletting: time and place

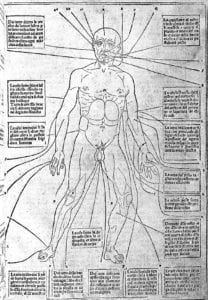

Figure 2. Woodcut of bloodletting man. 16th century. Wellcome Collection. Public domain.

The time and place to make an incision was of the utmost importance. Many factors had to be considered before opening a vein and some writers looked to the activity of the moon for temporal guidance. By the sixteenth century, it was common knowledge that the moon influenced all moisture on Earth, from the ebb and flow of the tides to the water that encouraged seeds to grow in soil. The moon was “the Mistress of . . . Moisture” and “the great Lady of Life and Growth” in the universe. As human bodies were comprised of the elemental qualities of heat and moisture, they were also influenced by its power.5 Early modern learned men explained this using the Ancient Greek macro-microcosmic model of the universe, where the complexion of human bodies (micro) corresponded to the nature of the wider cosmos (macro).

As blood is a fluid, its movement in bodies was governed by the moon. This was why many premodern observers tied the monthly process of menstruation to the changing lunar phases. In the case of bloodletting, blood moved quicker during the full moon, when the Earth was most exposed to its beams, but this did not necessarily make it the best time to undertake the practice. In his 1659 work Culpeper’s School of Physick (Fig. 1), seventeenth-century astrologer Nicholas Culpeper warned that it was difficult for practitioners to control the quantity of blood lost at this time. However, for menstrual disorders, he claimed that the strength of the moon’s power over the movement of blood needed to be high to restore the natural flow: “you will find it an Herculian task . . . to bring them down in the Wane of the Moon . . .”6

Once the time was determined, the practitioner then considered where the incision should be made on the patient’s body. Disease and disorder were treated by bleeding from a specific, nearby vein. For women suffering from menstrual disorders, the saphenous vein in the ankle was the most common place to bleed from. As the retention of menses was the most likely cause of menstrual disorders, bleeding from the ankle encouraged the body’s movement of blood down and through the womb again.7 However, if the disorder was caused by too much menstrual bleeding—for instance, from complications after childbirth—then bleeding a vein in the arm would slow down the flow, just as one holds a deeply cut finger above the heart.8

To modern observers, this notion of vicarious bleeding may seem strange, but to early modern patients and practitioners it was logical. Nosebleeds towards the end of a pregnancy were often assumed to be menstrual—a sign of the mother’s impending birth and the restoration of her monthly flow.9 Menstrual blood was by its nature a salubrious substance with various functions: it prepared the womb for pregnancy, fed the child in the womb, and after birth it was transferred from the womb to the breasts where it transformed into milk. As historians of the body have shown, “[i]n this world the fluid inside the body could apparently assume different forms, yet remain always the same substance.” Early modern bodies were porous and, crucially, their interiors were invisible. This allowed patients, and sometimes even practitioners, to imagine its inner workings in broad, seemingly contradictory ways: if an orifice was closed, matter could be persuaded across the boundaries of the interior organs and vessels, and out through another orifice.10 The permeability of bodies also explained why the external environment affected the health of human bodies, such as miasma (bad smells), but also cosmic entities like the moon.

Spatial and temporal rules for bleeding were easily accessible to patients and practitioners from every level of society. The moon was a ubiquitous presence for it illuminated darkened paths at night and, until the seventeenth century, was a common form of timekeeping, particularly for farmers, sailors, and menstruating women. Similarly, locating incision sites on the body was relatively straightforward. Not only was information shared orally, it was easily memorized and visualized using the omnipresent physical body. For those with some level of literacy, medical texts from cheap country almanacs to lengthy anatomical textbooks also provided illustrations of the “bloodletting man,” a diagram of a human body with labelled incision sites at major veins (Fig. 2). This figure was usually depicted as a man, but its knowledge was equally applicable to women. Even though women’s diseases were often considered a subsidiary of mainstream medicine in this era, bloodletting was a universal and highly accessible therapeutic practice that transcended boundaries of gender and education.

References

- Jane Sharp, The Midwives Book (London, 1671): 294.

- Michael Stolberg, ‘Menstruation and Sexual Difference in Early Modern Medicine’, in Andrew Shail and Gillian Howie (eds.), Menstruation: A Cultural History (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005): 90-101.

- Patricia Crawford, ‘Attitudes to Menstruation in Seventeenth-Century England’, Past & Present 91 (1981): 47-73.

- For early modern menstruating men, see: Gianna Pomata, ‘Menstruating Men: Similarity and Difference of the Sexes in Early Modern Medicine’, in Valeria Finucci, and Kevin Brownlee (eds.), Generation and Degeneration: Tropes of Reproduction in Literature and History from Antiquity to Early Modern Europe (Durham and London: Duke Press, 2001): 109-152.

- J. B., Hagiastrologia, or, The most sacred and divine science of astrology (London, 1680): 6.

- Nicholas Culpeper, Culpeper’s school of physick (London, 1659): 244-5.

- Jakob Rueff, The expert midwife (London, 1637): 109.

- Sharp, The Midwives Book: 294.

- Gabriella Zuccolin, and Helen King, ‘Rethinking Nosebleeds: Gendering Spontaneous Bleedings in Medieval and Early Modern Medicine’, in Bonnie Lander Johnson, and Eleanor Decamp (eds.), Blood matters: studies in European literature and thought, 1400-1700 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018): 79-91.

- Barbara Duden, The Woman beneath the Skin: A Doctor’s Patients in Eighteenth-Century Germany (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1991): 120-35.

RHIANNA ELLIOTT completed a BA in History at King’s College London and MPhil in History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine at the University of Cambridge. Her PhD research at Cambridge explores connections between lunar influence and women’s menstruating bodies in early modern England.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest & Highlighted in Frontispiece Volume 12, Issue 2 – Spring 2020

Leave a Reply