Elisabeth Preston-Hsu

Atlanta, Georgia, United States

|

|

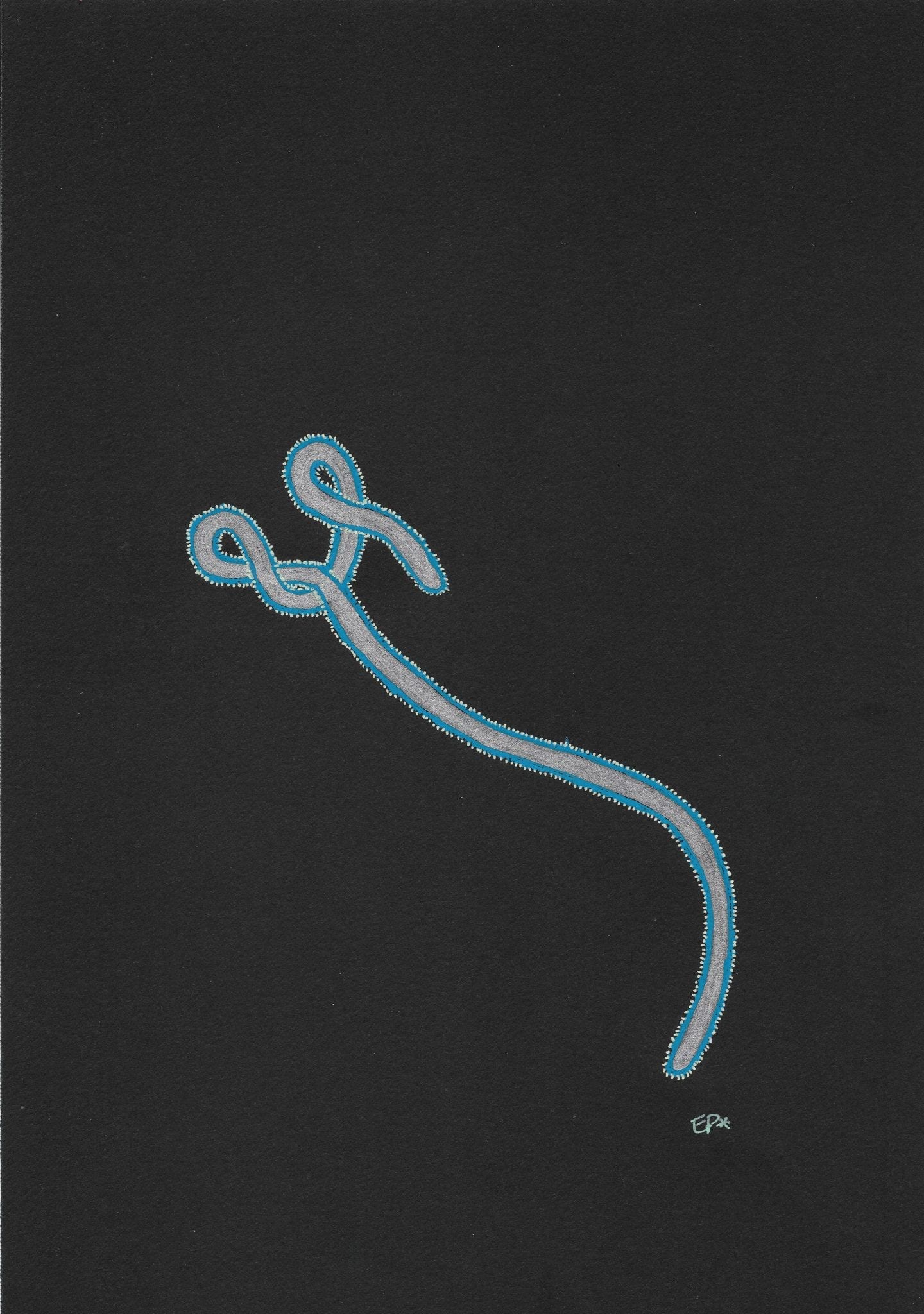

“Ebola in the Dark.” Drawing by Elisabeth Preston-Hsu, 2019, private collection |

In September 2014, my husband Chris boarded a plane from Atlanta, Georgia for the Democratic Republic of Congo, his first trip to Africa for work. We had just moved back to Atlanta two months before when he started a new career with the Centers for Disease Control. He would spend the next month in a remote jungle collecting data from the surrounding villages during an Ebola outbreak. Anything Ebola-related most certainly involved death.

Dread washed over me the day I dropped him off at the airport, although I tried to compartmentalize my feelings. Nervous, excited energy zipped through and around him. Though I knew his data collection did not involve caring for people sick with the virus or safely disposing the dead, there was a nib of fear that hung on his risk of exposure given the area he was to be stationed in.

When he unloaded the luggage from the trunk, I did not say “Good luck” or “Have a safe trip.” I did not even say “I love you.” I swallowed the prick of tears, got back into the car, and drove home with our three young children. I have only a vague recollection of what I said to Chris as we parted, but he repeated it to me later: “Be safe.”

Most updates came over Facebook and occasional text messages. Chris rode a motorbike with a Congolese colleague to investigate an Ebola-related death over forty kilometers from camp, the dirt path becoming a small river when a thunderstorm met them on the way back. He ate military rations. He drank jungle-warmed Bulleit whiskey with his boss a couple of times, the alcohol hitting Chris hard after not having any for weeks. Their team shared encampments with Médecins Sans Frontières (Doctors Without Borders) and crunched numbers on computers equipped with solar chargers. The Red Cross teams scattered through the region aided in body disposal and medical care.

Phone calls came intermittently on a military field phone, Chris’s voice reverberating tinny and far away. It was usually the same staticky conversation: How are the kids? How are you? Can I talk to them? Is Zoë okay in school? Almost seven-year-old Zoë, our oldest, did not deal well with her father’s absence, her anxiety manifesting in whirlwinds of tantrums and hateful words. I hate you, Mommy. I wish you would die. All she understood was that Daddy had gone to help sick people with a virus, a thing that was really small in people’s blood but it could kill. Including Dad. Maybe Mom.

As Chris melted in the jungle heat and grew an enviable beard, I took the kids swimming, continued their routine of school and daycare, and updated family and friends on Chris’s activities. Those updates became issues later, with some people avoiding us after Chris got back because they feared he was infected. Many people extolled his service and bravery but politely declined dinner invitations after his arrival home. They were just as anxious as Zoë, heady with updates and warnings from the media, while ignoring our explanations that he never came into contact with infected bodies.

The first Ebola patient treated in the United States had arrived in August 2014. Kent Brantly, a physician who became infected when doing missionary work in Liberia, had been treated at and released from Emory University Hospital, less than a mile from our house. Media helicopters awakened us at strange hours and paparazzi crowded the hospital’s front entrance as I drove by daily to pick up our two youngest children from daycare. Those reminders of Ebola dredged up my submerged fears while Chris was gone, often in odd dreams at night. Dreamworld viruses became wild colors embodied in growing amorphous shapes, floating in black and pushing me from sleep into gasping wakefulness.

But in time the more I reasoned with it, the more my dread faded. Logic. Chris was alive. There were no fevers, it was just hot outside. He was not seeing patients or handling the deceased, just collecting data. Washing his hands, washing his hands, washing his hands. That dread resurfaced when he was to arrive home in two days. What . . . if? I shook it off. Maybe it was just nervous excitement that my husband was finally coming home after a month.

I drove to the international terminal of Hartsfield-Jackson Airport on a sunny, breezy afternoon. It was cool enough that I could wear a fitted autumn-colored tweed blazer: the crisp air felt formal and my clothing needed to match. I strapped our one-year-old daughter in a baby body-carrier and walked into the entrance of the airport. There he was, after some rigorous questioning by customs agents. Chris smelled of grass and campfire smoke. Of sweat and pomegranate tart-sweet. I kissed him; his beard scratched my upper lip and I tasted that pomegranate and salty sweat. Our daughter gave us strong side-eye, Chris’s scent and facial hair completely throwing her off. Who was this man kissing her mother? She was not having it. But I was.

Whatever was in our blood did not kill us, though it felt it could harbor something that could. Anxiety creeping into nighttime dreams. A virus causing hemorrhagic fever. An ocean apart, now together again, alive.

ELISABETH PRESTON-HSU, MD, MPH, is a Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation physician in Atlanta, Georgia, with a practice focus on wound care and hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Besides practicing medicine, she has a strong interest in narratives in medicine, particularly the personal histories of her patients.

Winter 2020 | Sections | Infectious Diseases

Leave a Reply