Paulina Kowalińska

Wrocław, Poland

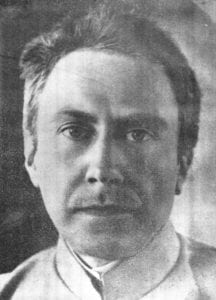

Ludwik Hirszfeld in 1916, during the Serbian war. Via Wikimedia. Public domain.

“To a far greater extent the group reactions have been used in forensic medicine for the purpose of establishing paternity. The possibility of arriving at decisions in such cases rests on the studies of the hereditary transmission of the blood groups; the principal factural results in this field we owe to the work of von Dungern and Hirszfeld. As a result of their research it became established that both agglutinogens A and B are dominant hereditary characteristics and that transmission of these characteristics follows Mendel’s laws. The importance of this lies in the fact that in man there is scarcely any other unequivocally identifiable physiological characteristic with such simple hereditary behaviour.” – Karl Landsteiner1

Though it was Karl Landsteiner who in 1901 discovered that different blood groups exist,2 there was another man whose groundbreaking research changed our understanding of blood. He was eighteen years old when entering the University of Würzburg in 1902 to study medicine. In 1907 he wrote a thesis about blood agglutination and received a PhD at the University of Berlin where he had transferred, and just three years later he and von Dungern—a fellow researcher and an internist—became responsible for the naming convention A, B, AB, O that has been used since 1928.

His most significant discovery, however, came when he was continuing his research on blood groups and decided to test whether Mendel’s inheritance principles applied to blood. Working at Heidelberg University in 1910, he conducted tests on the staff and was able to prove that blood groups are indeed inherited in the same way as other genetic traits. Spurred on by this finding, he continued the studies with his wife Hanna Hirszfeld when stationed on the Macedonian front as a soldier of the Serbian army. The site was nearly ideal for research—other soldiers and refugees who became test subjects hailed from all over the world, and due to a malaria outbreak, many doctors specializing in tropical diseases were present. Hirszfeld seized the chance. Being able to collect data from 8,000 people from various countries and collaborate with other doctors to further his blood research was a remarkable opportunity. He tested for connections between blood groups and hair color, race, gender, age, social status, and country of origin.3 Landsteiner described some of the results in his Nobel lecture:

“The relative frequency of the individual blood groups in various races has been dealt with in a well-nigh endless number of communications since L. and H. Hirschfeld made the noteworthy observation that characteristic differences in this connection are found in different races. Their most important finding was that group A is more frequent than B in northern Europeans, whereas the position is reversed in several Asiatic race.”1

Some other conclusions suggested that blood type might have an impact on a person’s health. For example, people with the type B were suggested to live the longest.

Scientists from around the world still research this topic, even though Hirszfeld’s studies were carried out almost a century ago. In 2004 Shimizu et al presented a study in which they “compared frequencies of ABO blood group in 269 centenarians (persons over 100 years) living in Tokyo,” which showed that blood type B was associated with exceptional longevity.4 However, a study in the US showed the opposite—that type B “may be a marker for earlier death.”5 In 2015 Mengoli et al researched the same issue in Italy and found that “the number of subjects with group A increased with age, the numbers with group AB and B decreased, indicating a negative association between these blood types and longevity.”6

Despite not obtaining clear answers from these studies, the mere possibility of blood groups affecting longevity hinted at a distinct influence on health. The question was whether people with certain blood types were more prone to life-threatening diseases. By testing thousands of blood samples, Hirszfeld had created a new branch of science—seroanthropology,7 dedicated to examining serological differences between people.

Landsteiner mentioned Hirszfeld in his Nobel lecture in 1930, noting the importance of discovering that “both agglutinogens A and B are dominant hereditary characteristics and that transmission of these characteristics follows Mendel’s laws.” 1 This became the basis of successful blood transfusions, could be used to test paternity, and assisted in forensic science.

His studies brought Hirszfeld some controversial fame during the most popular court trial of the Second Polish Republic—the case of Rita Gorgonowa. Gorgonowa, a governess in the house of a Lwów architect, Zaremba, was accused of murdering the architect’s daughter Elżbieta on December 30, 1931. The ensuing investigation and trial lasted almost two years, with Gorgonowa refusing to confess. Much public attention surrounded the case. At one point, traces of blood were found on the governess’ coat and handkerchief, condemning her, but Hirszfeld questioned the court specialists’ examination of said blood. Eventually, however, Gorgonowa was found guilty and sentenced to prison.8

Hirszfeld was not only a hematology pioneer; he also did not hesitate to personally aid those in need, and he fought for what he believed in. Having been born to a Jewish family, he faced obstacles in both publishing his work and remaining a lecturer in occupied Poland. During the Siege of Warsaw in 1939, he was urged to flee to save himself and his family, but he opted to stay behind and organize a blood transfusion camp for the soldiers. Afterwards he was forced to live in the Warsaw ghetto where he continued to secretly teach about medicine and treat typhus with a smuggled vaccine.9 After the war was over, Hirszfeld published his autobiography, The Story of One Life, and moved to Wrocław where he remained until his death nine years later.

Ludwik Hirszfeld was an exceptional scientist who combined thorough research with his practical approach and bravery. In 1950 he was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Medicine. He did not win it, and though he is often overlooked in the world of hematology, Poland remembers him to this day. I live in the city where he taught for a few years and there are reminders of him everywhere. The Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy PAN founded by him functions to this day. He was the first dean of the medical faculty at the University of Wrocław. I have been inspired by living in the city where a fellow Pole changed the lives of so many with his perseverance and a brilliant mind.

References

- Landsteiner, K. (1930). On individual differences in human blood. Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1930. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/medicine/1930/landsteiner/lecture/

- “ABO blood groups”, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ABO_blood_group_system

- Allan, T. M. Hirszfeld and the ABO blood groups. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1963 Oct, 17(4): 166–171.

- Shimizu, K. et al. Blood type B might imply longevity. Exp Gerontol. 2004; 39:1563 – 1565.

- Mark E. Brecher, MD, Shauna N. Hay, MPH. ABO Blood Type and Longevity. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. Volume 135, Issue 1, January 2011, Pages 96–98.

- Mengoli C, Bonfanti C, Rossi C, Franchini M. Blood group distribution and life-expectancy: a single-centre experience. Blood Transfus. 2015;13(2):313–317.

- “Ludwik Hirszfeld”, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludwik_Hirszfeld

- “Rita Gorgonowa”, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rita_Gorgonowa

- Hirszfeld, L. The Story of One Life. University Rochester Press. 2010. Originally published in Polish in 1946.

PAULINA KOWALIŃSKA is a Computer Science engineer who graduated from Wrocław’s University of Science in 2019 and is interested in writing and medicine.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Leave a Reply