Anusha Pillay

Raipur, India

|

|

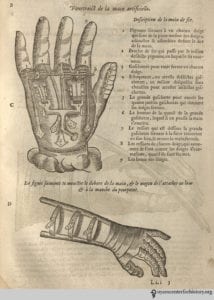

Bloodletting from the arm. Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0. |

“His pole, with pewter basins hung,

Black, rotten teeth in order strung,

Rang’d cups that in the window stood,

Lin’d with red rags, to look like blood,

Did well his threefold trade explain,

Who shav’d, drew teeth, and breath’d a vein.”

– The Goat without a Beard by John Gay

Barbers today are primarily engaged in caring for their patrons’ hair and nails. Until the nineteenth century, however, they were known as barber-surgeons and offered many other services, such as pulling teeth, cutting out hangnails, setting fractures, giving enemas, and lancing abscesses.1

The barbering occupation began in ancient Egypt, where both men and women wore wigs and the nobility often shaved their entire bodies. The wealthy citizens and royalty had personal slaves, who dressed their wigs and shaved them—the precursors of modern-day hairdressers. Eventually there developed an independent class of barbers, who would perform these functions for everybody in society.

The Greeks also required skilled barbers because their long hair and curled beards demanded great care. Alexander the Great, for strategic reasons, urged his men to cut their hair and shave their beards before going into war, necessitating a set of skilled haircutters. With the growing influence of the Greek state, they entered Roman territory where they set up street stalls.2

The Hippocratic Oath prohibited doctors from performing surgery on those suffering from kidney stones, bladder stones, or gallstones. This job was reserved for a different professional class. Their skill with precise instruments and their affordability compared to the local physician made barber-surgeons the first choice for surgical procedures. These skilled individuals were found in settled communities across the world—from the American colonies, where European colonists made use of the surgical competence of the Native Indians, or in China, where traveling barbers drifted along the streets, ringing a bell to announce their presence.

After the eleventh century AD, the roles of physicians and surgeons became clearly demarcated. Physicians resided in courts and palaces and were almost exclusively in the service of the wealthy. Since they studied and spoke fluent Latin, and their knowledge was held in high regard, the practice of surgery was considered beneath their dignity. It was the barber-surgeons who had to take on the task of tending to the injuries and afflictions of the masses—soldiers, peasants, monks, and workers.

While physicians were accredited and licensed by universities, barber-surgeons did not have that luxury. They had to apply to the trade guild and become apprentices. They learned to deal with a range of tasks such as caring for wounds and lacerations, burns and skin rashes, setting fractured bones and dislocated limbs, venereal diseases, lancing infections, topical applications, and applications of poultices. The more skilled barber-surgeons would also perform more critical procedures such as trepanation, amputation, cauterization, and delivering babies. They were especially needed in times of war, such as during the campaign of Henry V in 1415, and during the Thirty Years’ War from 1618 to 1648. In wartime barber-surgeons commonly performed amputations, and they also were adept at trepanation, drilling a hole in the skull of the patient, a procedure considered to be a remedy for seizures and certain behavioral problems, or to allow demons and evil forces to escape.

|

|

Le Petit Lorrain. From the 1633 edition of Les oeuvres d’Ambroise Paré. New York Academy of Medicine. |

The barber surgeon was also expected to deal with more unclean tasks such as bloodletting, leeching, cupping, and pulling teeth. Bleeding was sometimes done to let out the bad or morbid blood from the body; and it was done by cupping, applying leeches, or cutting into a vein and letting the blood flow into a small basin. As bleeding became one of barbers’ main responsibilities, they would indicate their presence in the marketplace with a red and white striped pole, the colors evocative of the blood and rags involved in bloodletting. This pole was topped by a small basin, signifying the vessel in which they would collect the blood.3

In 1163 a papal decree forbade monks from shedding blood, leaving all surgical tasks to the skilled barbers. In addition to bloodletting, they now were expected to carry out almost all surgical and dental operations, as well as more unsavory procedures such as embalming and autopsies.

The twelfth and thirteenth centuries witnessed the rapid growth of secular universities and an increased study of medicine, anatomy, and surgery, resulting in a split between the academically trained surgeons, who wore long robes, and the barber surgeons, who wore short robes. The coexistence of the two separate guilds of surgeons and barber-surgeons was marked by an uneasy peace.4

Certain barber-surgeons became exceptionally skilled at carrying out surgical procedures, such as Ambroise Paré, widely regarded as the father of modern surgery. A barber-surgeon apprentice at the Hôtel-Dieu, he learned anatomy and surgery and in 1537 was employed as an army surgeon. By 1552 he had become so popular that he was appointed surgeon to the king. Notable among his many accomplishments was his use of an ointment of egg yolk, oil of roses, and turpentine for war wounds instead of boiling oil and cauterization. He also introduced the practice of ligating arteries instead of cauterizing them during amputation, as well as the implantation of teeth, artificial limbs, and artificial eyes made of gold and silver. He invented many scientific instruments, popularized the use of the truss for hernia, and was the first to suggest syphilis as a cause of aneurysm.5

Although England’s King Henry VIII famously merged the guilds of surgeons and barbers in 1540, the former decided that surgery was their area of expertise after all, and as time went on they gained the upper hand. In France surgery got a boost under the rule of Louis XIV. His grandson, Louis XV, would further this when he established five chairs of surgery at the college of St. Côme. Finally, in 1743, every barber and wig maker in France was forbidden to perform surgery. Two years later, barbers and surgeons were also completely separated in England. In 1800 their guild became the Royal College of Surgeons, while barbers were left to deal with hair and other cosmetic concerns.6

Nowadays the friendly neighborhood barber is no longer expected to address the health issues of his customers. But even now they are likely to perform one key function, that of lending a patient ear to their customers and often reassure them. Before mental health and psychiatry were established as a separate disciplines, barber-surgeons were probably the confidants of patrons in distress. They most certainly were a vital part of medieval European history. To let their accomplishments fade into oblivion would be a great disservice to their memory.

References

- How Barbers became Surgeons- Gizmodo

- The Gory History of Barber Surgeons- Medieval medicine gone mad

- From Haircuts to Hangnails- The Barber-Surgeon, by Elizabeth Roberts

- The Gory History of Barber Surgeons

- The Ambroise Paré International Military Surgery Forum

- The Badass History of Barber Surgeons

ANUSHA PILLAY is currently pursuing a BTech in Metallurgical and Materials Engineering at the National Institute of Technology, Raipur. She enjoys reading and writing. She has a keen interest in the intersection of literature, history, gender, and culture.

Submitted for the 2019–2020 Blood Writing Contest

Winter 2020 | Sections | History Essays

Leave a Reply